China’s premier, Li Keqiang, has called for options to be examined for the hugely ambitious western section of the South-to-North Water Diversion project.

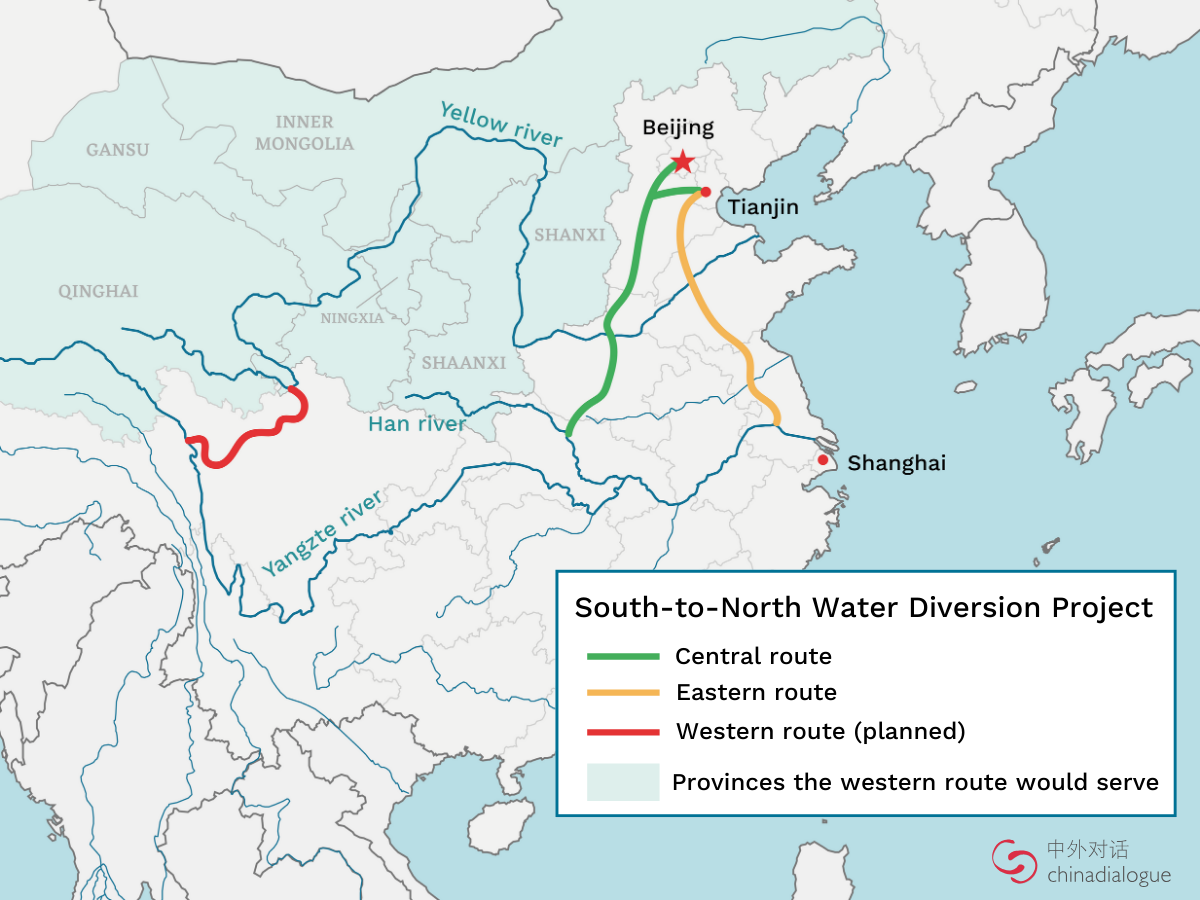

The idea of diverting water from China’s wet south to its dry north was first proposed in 1952. Today, the project consists of an eastern, a central and several potential western routes. The central one, completed in 2014, takes water on a 15-day journey from Hubei province more than 1,400 kilometres north to Beijing and Tianjin. The eastern one began transferring water from Jiangsu to Shandong and Tianjin in 2013.

The even more challenging western route, which would link the Yangtze and Yellow rivers across the Tibetan plateau, has never left the drawing board due to concerns about its environmental and social impacts. Talk of it has now resurfaced amid an economic slowdown in China. Although construction could stimulate the economy, there are good reasons why the idea has been dormant for so long.

Various possibilities

The South-to-North Water Diversion is both the most expensive and expansive Chinese infrastructure project since 1949. Construction began in 2002, and hundreds of thousands of people were relocated to make way. It brought fundamental changes to the hydrology and ecology of both the Yellow and Yangtze river systems.

The two existing routes – eastern and central – siphon off water from the lower and middle reaches of the Yangtze, respectively.

Ideas for the western route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project can be split in two: some extremely ambitious proposals from the public, and a more modest one by the government.

The official plan originated from the Ministry of Water Resources’ Yellow River Commission in 2001. Water would be taken from Sichuan tributaries in the upper reaches of the Yangtze, such as the Yalong and Dadu. A huge dam system would raise the water level, allowing it to flow through channels to the upper reaches of the Yellow river, from where it would progress into Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi and Shanxi. Ultimately, 17 billion cubic metres of water would be diverted per year, enough to meet the water shortages predicted for the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow river by 2050.

The more outlandish, unofficial proposals include a canal linking Shuomatan point in Tibet with Tianjin, and another plan to divert water from the same area to Xinjiang. These schemes would feed China’s north not just from the Yangtze but from transnational rivers, including the Yarlung Tsangpo, the Nu and the Lancang (which become the Brahmaputra, the Salween and the Mekong once they flow beyond China’s borders).

The Tibet–Tianjin canal was proposed late last century by Guo Kai, a retired technical cadre. It would see 200 billion cubic metres – the equivalent of four Yellow rivers – diverted from the Yarlung Tsangpo (the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra) to the Yellow river.

The proposal to divert water to Xinjiang was put forward in 2017 by another non-specialist, Gao Gan. This “Red Flag River” scheme would stretch 6,188 km, only slightly less than the Yangtze itself, and divert 60 billion cubic metres of water, more than the annual flow of the Yellow river.

Various opinions

Studies of the western route got underway in 2018, after an August announcement by the Yellow River Commission. These include an evaluation of the trends in water supply and demand in the Yellow river basin and the potential for water-saving schemes. The official route is receiving an in-depth examination, while the more ambitious alternatives are getting initial assessments.

The official western route would cross a mountainous region 3,000–4,000 metres above sea level. The terrain here is complex: seismically active, environmentally vulnerable and populated by minority groups. Construction and maintenance would be hugely expensive.

The unofficial proposals would be even more challenging partly because of their international dimensions.

Experts hold differing views on both approaches.

The harshest critics have called the unofficial schemes “fantasy”. Qian Zhengying and Zhang Guangdou of the Chinese Academy of Engineering said in a 2002 report to the State Council that for the foreseeable future they would be unfeasible and unnecessary.

Speaking at Hong Kong University in 2006, former water minister Wang Shucheng described the Tibet–Tianjin scheme, which would link five different rivers via five canals to feed the Yellow river, as “unneeded, unfeasible, unscientific”. He pointed out that the Yellow river already sees flooding in the wet season and an additional 200 billion cubic metres of water would cause issues for existing dams, hydropower plants and cities. The economic and environmental costs also make the scheme impractical, he said.

If we conserved water properly, would it be necessary to divert it at all?

But Zhang Boting, deputy secretary of the China Society for Hydropower Engineering, is a fan of an expanded western route, saying water from the Yarlung Tsangpo, Nu and Lancang would help relieve China’s water shortages. He points out that while China currently draws no water from transnational rivers, it should do so in proportion to the length each river flows within its borders: “On average, over 100 billion cubic metres of water flow through the Yarlung Tsangpo within Chinese borders every year, but we make no use of it at all. There’s only a bit over 50 billion cubic metres of water in the Yellow river, yet that waters half the country. We should draw water from transnational rivers.”

It is the less ambitious plans, Zhang thinks, that are impractical. He believes drawing water from the Yangtze would affect hydropower facilities such as the Three Gorges Dam, so there will be more opposition. “Taking the water away is like taking their money away,” he argues.

Fan Xiao, a senior engineer with the Sichuan Bureau of Geology’s regional survey team, has a different view to Zhang: “You don’t have to remove the water to make use it. The water is maintaining the regional ecology; that’s an important function too. Dam building on the Lancang is already having an impact on the Mekong downriver.”

Why not leave well alone?

The crux of the disagreement is over balancing water use with environmental protection.

Since 2006, a survey team founded by independent geologist Yang Yong has been studying the areas water would be drawn from, channelled through and delivered to. They have concluded that seven constraints have not yet been fully addressed. These include impacts on the natural balance of the Yangtze source region, on flood seasons on the Yellow river, and on climate.

After 13 years of study, Yang Yong maintains that a western route of any sort is unnecessary. He points out that climate change is making China’s northwest warmer and wetter, and that human migration to the east as well as a shift away from heavy industry will relieve water shortages. In short, Yang believes that understanding changes in climate, population, society, environment and technology should be prioritised over engineering solutions.

Fan Xiao isn’t convinced that the northwest of China is getting warmer and wetter, but otherwise holds a similar view. He says a western route wouldn’t solve water shortages and that conservation measures should be implemented before more water is brought in: “If we conserved water properly, how much would we need to divert? Would it be necessary at all?”