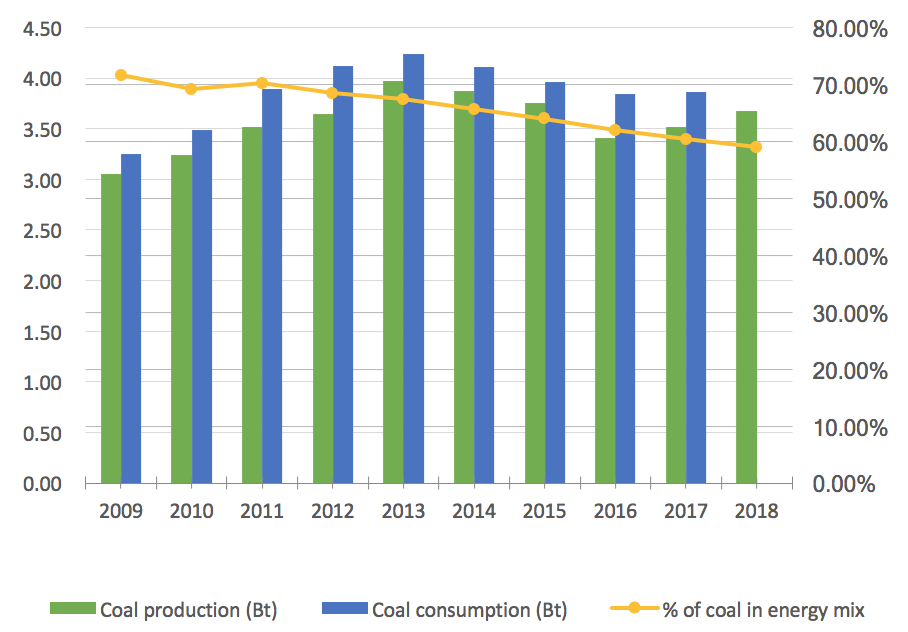

Coal consumption peaked in China in 2013 at 4.24 billion tonnes. Then government efforts to improve the energy structure and tackle pollution saw coal use fall between 2014 and 2016. Following a small increase in 2017 consumption rose again in 2018, according to figures published on February 28 by the National Bureau of Statistics.

Experts say this second consecutive annual increase suggests China may have de-prioritised energy saving and emissions reduction, owing to the pressures of its slowing economy. Another wave of infrastructure investment is also slowing the decoupling of the economy from energy consumption.

A faltering transition?

The rebound in coal consumption has increased China’s CO2 emissions. Greenpeace calculates that they grew by around 3% last year, the largest increase since 2013.

There have been a number of recent proposals for coal consumption to be allowed to grow in China, so as to reduce pressure on energy supplies, with calls for more coal gasification or liquification. Zhou Dadi, head of the National Development and Reform Commission’s Energy Research Institute, said in response that “regardless of how much you improve the technology, coal remains inefficient and carbon-intensive. It would be a step backwards to go from global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions to… a return to reliance on coal.”

Commenting on the idea of “clean coal power”, He Jiankun, chair of the academic board of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, told chinadialogue that “coal can be used in cleaner ways, but it can never actually be clean and low carbon. Don’t get those ideas confused.”

He added that China’s green transition is a tough challenge: a quick shift from peak carbon to zero carbon. But if China can make it happen, it will have more control over its future.

Positive trends

Despite some increase in coal use, consumption has not returned to 2013 levels and the overall trend remains downwards.

In 2018, coal accounted for 59% of China’s total energy consumption, 1.4 percentage points down on the previous year and the first time coal has accounted for less than 60% of primary energy. Clean energy, which in China includes natural gas alongside hydro, solar and wind, accounted for 22.1% of total energy consumption, up by 1.3 percentage points.

China is expected to reach its 13th Five Year Plan goal of reducing coal to under 58% of total energy consumption in 2020.

Zhou Dadi said that 2019 will be a crucial year for intermediate targets in the government’s “assault on air pollution”. With end-of-pipe measures in coal power stations, such as sulphur and nitrate scrubbers and dust collectors, having been installed on a wide scale, the next stage must rely on changes to the energy structure.

Rapidly growing electricity demand

The new 2018 data also showed a 7.7% increase in electricity generation and a 8.5% increase in total electricity use. These are new highs since the economic slowdown started in 2012, and outstrip the year’s GDP growth of 6.6%.

On one hand, this shows accelerating cleaning up of end-user energy consumption: electricity is replacing gas and oil. But it also reflects greater investment in infrastructure as a response to the economic downturn, with energy-hungry industries such as coal, steel, cement and chemicals recovering and swelling electricity demand. These industries remain the drivers of economic growth in China, making reductions in coal-use less achievable.

A new round of industry and construction stimulus would condemn global emissions to grow for another several years.

The jump in electricity consumption highlights the complexity of China’s green transition. Pollution cuts in some industries mean higher electricity consumption. The steel industry is an example. Yuan Jiahai, professor at North China Electric Power University’s Economy and Management College, explained that with inefficient capacity being eliminated, more electric furnaces being used, and environmental-protection equipment coming online, electricity use in the steel industry rose 9.8%. That is 8.6 percentage points more than the previous year, and equates to a contribution of 0.8 percentage points to the increase in total electricity consumption.

An infrastructure revival?

Some analysts worry that increasing economic uncertainty may lead the Chinese government to again promote growth with a major stimulus package.

In China, economic stimulus often means infrastructure construction. Some such construction may be necessary, but it spurs the production of energy-intensive building materials (like steel and cement) and demand for electricity, and so increases coal consumption and emissions.

As the world’s largest carbon emitter, China’s choices affect global climate efforts. Lauri Myllyvirta, an energy analyst with Greenpeace, said in an article last November that “a new round of industry and construction stimulus would condemn global emissions to grow for another several years.”

So far the government has avoided a comprehensive stimulus package in favour of more targeted measures, such as investing 86 billion yuan (US$12.8 billion) in high-speed rail and subways.

Iris Pang, an analyst with international financial services group ING, estimated in November that China would inject around 4 trillion yuan (US$600 billion) into the economy in 2019. Based on data on investment in fixed assets, she also predicted that infrastructure investment would be the main driver of economic growth in 2019. This means demand for metal products will continue to grow.

But as recently as last week, Premier Li Keqiang reiterated that there would be no “flooding” of the economy with stimulus.

Yuan Jiahai indicated that the macroeconomic growth outlook for 2019 is bound to be tougher than 2018, due to a global slowdown and the US–China trade war. He said the government has emphasised “infrastructure investments need to be stable… in sectors such as transportation and power.” But he added “I don’t expect that economic stimulus will lead to significant incentives for energy-intensive industries.”

According to a document published on the National Development and Reform Commission’s website on February 26, this year will see increased “new-style infrastructure investment” in crucial technologies, high-end equipment, and key components and parts.” Liu Jia, a researcher with Renmu Consulting, said “In industry terms, the quality of China’s infrastructure construction is increasing. But it’s still not clear from the data how this construction will affect carbon emissions.”

![Fears of river diversion have led to protests against a Chinese funded hydropower project in Kashmir [image by: Ghulam Rasool]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2019/03/Neelum1-Ghulam-Rasool-300x200.jpg)