Apple’s appeal of a court order to unlock a dead terrorist’s iPhone for the FBI has attracted huge public attention and support from privacy advocates, fellow tech companies and even human rights groups. Apple has taken advantage of the heated debate to position itself as a champion of digital privacy rights.

By contrast, public attention to the abuse of workers and poor conditions in the factories of Apple’s suppliers has long faded. It is now over six years since 18 young workers committed suicide in Taiwanese-owned Foxconn factories – at the time the sole manufacturer of iPhones.

Foxconn locations in Greater China, 1974-2016. (Sources: Foxconn Technology Group websites)

Apple has since shifted part of its orders to other suppliers to minimise the reputational risks and intensify pressure on Foxconn, but has failed to address the fundamental problem in its supply chains. The relentless demands Apple imposes on its manufacturing subcontractors for low prices and high productivity continue to jeopardise workers’ health and well-being. In its latest Supplier Responsibility Progress Report released in March Apple neither disclosed the unit price for iPhone assembly nor the product delivery time.

Between June 2010 and February 2016, we joined hands with a multi-university research team and Hong Kong-based labour rights group SACOM (Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehavior) to conduct fieldwork in Greater Shanghai, Guangdong, Sichuan, Henan, and Shanxi provinces, where Foxconn recruits large numbers of workers and student interns to fuel its 24-hour assembly lines.

As Foxconn has extended its empire further inland with the help of government subsidies, labour conflicts have repeatedly erupted, prompting image-conscious brands to call for changes at their suppliers. Unfortunately, companies prefer quick fixes, such as the toll-free hotline at which Foxconn workers can report “any abuses” to Apple directly, rather than rethinking their drive for speedy production at “competitive prices.” This overwhelming pressure is the major source of contradictions in the buyer-driven global production model.

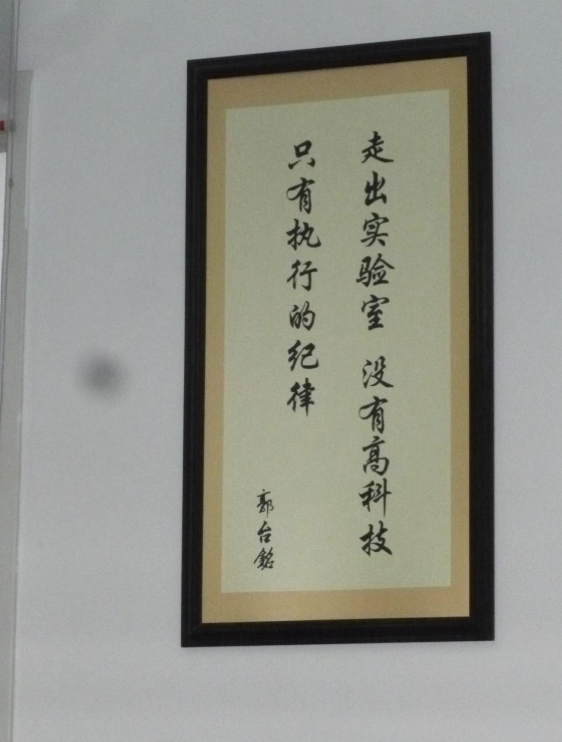

“Growth, thy name is suffering”—Gou’s Quotations

Gou’s Quotations is a collection of aphorisms reflecting Foxconn founder and CEO Terry Gou’s work philosophy.

Outside the lab, there is no high-tech, only implementation of discipline.

Execution is the integration of speed, accuracy, and precision.

Value efficiency every minute, every second.

Achieve goals or the sun will no longer rise.

The devil is in the details.

Apple’s new ultra-thin iPhones scratch so easily that they must be held in protective cases during assembly. This makes workers’ delicate operations even more difficult, but no extra time is given to complete the work. A worker explained, “The precision requirement for the screens of the iPhone cannot be detected by human eyes. We use microscopes to check product appearance. It’s impossibly strict.” These new standards are causing workers painful eye strain and headaches.

The environment, health and safety hazards at Apple’s suppliers have continued to draw attention from labour and green groups at home and abroad. A vigorous civil society campaign to clean up Apple has waged in China, with a series of reports published by a coalition of domestic green groups exposing serious violations at some of the company’s contractors. This highlighted the potential of Chinese consumers to exercise oversight over the brands that produce their everyday products.

Read also: Living with Foxconn

However, when it comes to workers’ conditions, little appears to have changed. Workers we interviewed reported other major health concerns. At Foxconn Kunshan’s factory near Shanghai one worker said, “Prolonged direct contact with nickel in metal alloys and electroplating materials affects human skin. If I already have a rash, it will itch even more.” At Foxconn Chengdu’s “iPad city” workers operated polishing machines that produce clouds of microscopic aluminium dust 12 hours a day. “I’m breathing aluminium dust at Foxconn like a vacuum cleaner,” said one worker. With the workshop windows tightly shut, workers felt as if they were “suffocating.”

Student interns or cheap workers?

One of the biggest concerns that emerged about Foxconn’s labour practices is its “internship” programme for teenage students. In a Foxconn business group that exclusively serves Apple, 28,044 “student interns” from over 200 schools were working alongside rural migrant workers in Shenzhen in 2010, a six-fold increase from 2007. Overall, Foxconn used the labour of 150,000 student interns — 15% of its entire Chinese workforce — during the summer of 2010. It continues to hire new interns as cheap and flexible labour today.

The Chinese government has established massive student internship programmes that purport to offer paid training for secondary vocational school students. The training is supposed to be related to students’ field of study and working over eight hours a day is strictly prohibited.

Sichuan Zhongjiang Vocational School students, many of them 16 years of age, arrived at Foxconn Chengdu in the morning on 3 March 2011 to begin “internships,” which lasted from three months to one year. (Photo credit: Jenny Chan)

However, our interviews with 38 interns from eight schools revealed that local governments and Foxconn collude in evading these rules. Sixteen-year-old Cao Wang (the names of all interviewees are aliases), who was studying textiles and fashion, was required to do nothing but tighten screws for 12 hours a day throughout her internship; Chen Hui, a 16-year-old construction student, polished iPad casings; Yu Yanying, 17, studying petro-chemistry, stuck labels on iPad boxes.

One student explained: “Our teacher announced that every vocational school in the province had to cooperate with the local government and send students to Foxconn to take up internships.”

But there was in fact no skills training program and no assignment based on their field of study. From day one, students did the same jobs as workers in the factory for up to one year, saving Foxconn money and providing it with a disposable labour force that could be “sent back to the school” when peak production periods had passed.

Here

The foam lining highlights the perfection of Apple

But not our tomorrow

The scanner repeatedly announces “OK”

But not the “FAIL” in our hearts

24 hours a day, the blinding lamps illuminate the iPhones

Scrambling our days and nights

Thousands of repeated movements accomplish impeccable work

Testing the limits of our painful, numb shoulders

Each screw turns diligently

But they can’t turn around our future.

—A Foxconn worker’s poem

On 18 February 2014, Jacky Haynes, senior director of Apple’s Supplier Responsibility Program, briefly addressed our concerns about protecting the rights of workers and teenaged student interns. “Over the years, we have increased the prices we pay to suppliers in order to support wage increases for workers. Confidentiality agreements prevent us from providing the data you’re requesting,” she said. In other words, Apple, the world’s most profitable tech company, provided no evidence to substantiate its claim these price increases were passed on to workers as higher wages.

The lives of Chinese workers

The Foxconn suicides can be understood as an extreme form of labour protest to expose an inhumane workplace. But many more workers are standing up to defend their rights and interests in other ways. Text messaging and online group discussion services have facilitated faster organising and more face-to-face meetings in factory dormitories and other private spaces. In past years, work slowdown, strikes, riots, massive suicide threats, and lawsuits were staged among angry workers, calling for reform of enterprise-level trade unions. On 5 October 2012, nearly 3,000 workers bypassed the company trade union and walked out of the workshop, paralysing dozens of production lines at Foxconn’s Zhengzhou “iPhone city” in central China. Following disruptions during the day shift, senior managers simply imposed tighter deadlines and more stringent quality standards on night-shift workers. In that case, the workers failed to win the rest periods they sought.

“Realise the great Chinese dream, build a harmonious society,” intones a government banner. The definition of that dream and the determination of who may claim it are fiercely contested by workers and by the Chinese state. The world’s consumers should give workers’ struggles as much attention as they give to Apple’s new role as a principled protector of digital privacy.

Acknowledgement:

We thank Amanda Bell, Matthew A. Hale, Nicki Lisa Cole, Beth Walker, and editors of chinadialogue for their intellectual support and editorial advice. The workers’ interviews and poems in the original Chinese, as well as the company statements and the field research notes, are on file with the authors. This publication arises from research funded by the John Fell Oxford University Press (OUP) Research Fund (ref 152/015).