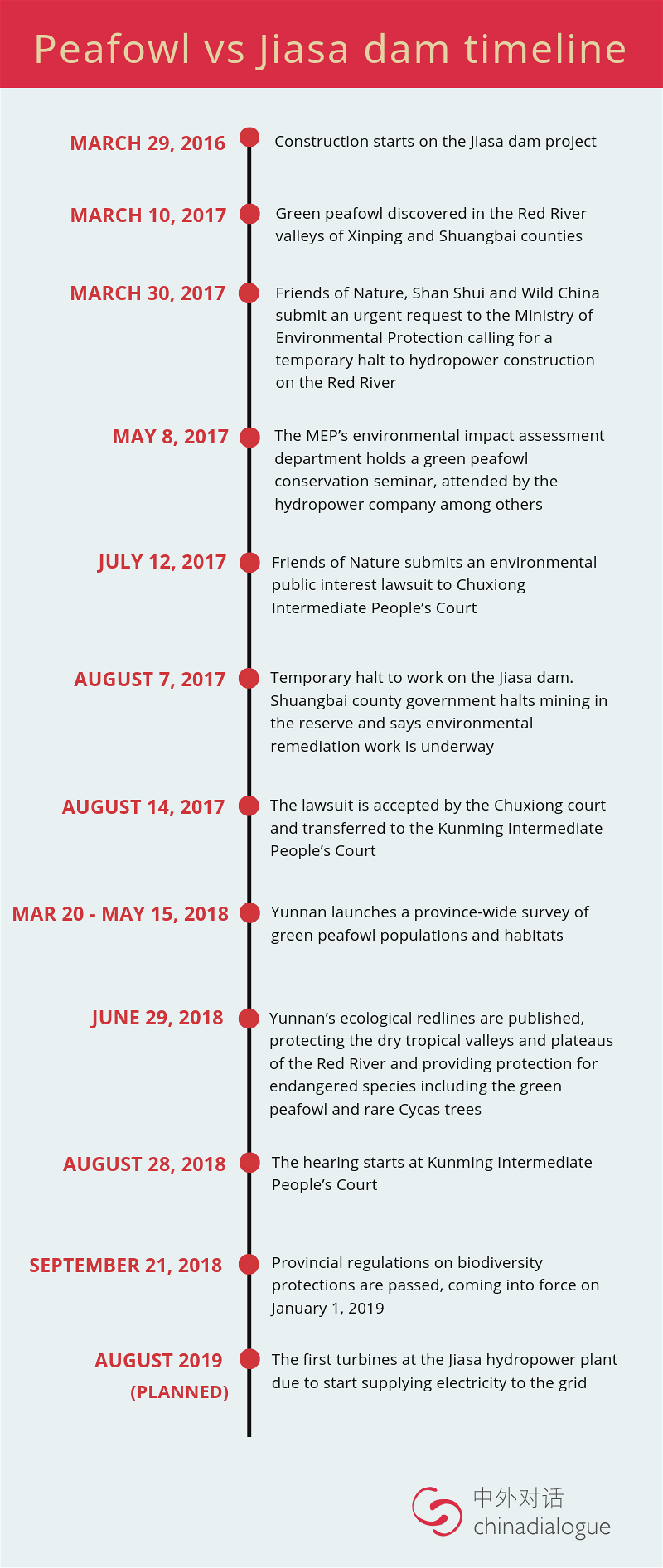

Conservation group Friends of Nature has asked courts to halt construction of a hydropower plant on a stretch of China’s Red River known as the Jiasa to protect the last major habitat of the endangered green peafowl. The case opened in August at the Kunming Intermediate People’s Court.

Many international rivers flow through Yunnan province in China’s south-west, including the Mekong, Salween, and the Red River, which flows onto Vietnam. The rivers have lots of hydropower potential because they drop sharply in altitude, but dam building has been dogged with controversy over regional politics, environmental impacts and the relocation of local residents.

The lawsuit in question is the first environmental public interest case in China aimed at preventing the loss of an endangered species. It highlights the environmental risks of more hydropower development in one of China’s biodiversity hotspots.

Peafowl vs big dam

The 3.7 billion yuan (US$532 million) Jiasa Hydropower Plant, in the Yunnan city of Yuxi, will generate 270 megawatts of power. Filling the plant’s reservoir will inundate large expanses of land upstream, including core habitats for the green peafowl.

Concerned about the risk to endangered species and damage to tropical rainforests, Chinese environmental groups Friends of Nature, Shan Shui Conservation Centre and Wild China brought an environmental public interest case against the dam builders (a local subsidiary of the China Hydropower Engineering Consulting Group) and the agency responsible for the environmental impact assessment, Kunming Engineering. The lawsuit demanded a halt to construction, with no blocking of the flow of the river or felling of trees in the reservoir area.

The publicity arising from the lawsuit led to a temporary halt to construction.

Secretary-general of Friends of Nature, Zhang Boju, said that “the requests in our lawsuit are simple and clear: we’re not asking for any compensation, just a halt to infringement, removal of risks, and no restarting of construction”.

Alone and endangered

The green peafowl (pavo muticus) was once common in China. Yunnan’s ethnic minority Dai people call it the golden peafowl because its feathers change colour from green to blue, to copper and gold, depending on the angle of the light.

In 2009 the green peafowl was listed as endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s red list. In 2017 Yunnan’s provincial authorities listed the green peafowl as critically endangered.

Habitat loss is a key reason for the birds’ demise. Its ideal habitat is in the broad valleys of tropical dry deciduous forest, but these have been shrinking, replaced with commercial crops such as rubber, tea, coffee, bananas and mangos.

New research by Chinese scientists published in Avian Research, an international journal, showed that the distribution of the bird has reduced by 60%. In the 1990s there were an estimated 800-1100 green peafowl in Yunnan alone. Kong Dejun, associate professor at Kunming University’s Department of Life Science and Technology and co-author of the paper now estimates there are only 500 left across China.

The construction of cascades of hydropower dams has shrunk green peafowl habitats. As dams on the Lancang River have been completed, expanses of tropical rainforest have been inundated, leaving the valleys of the Red River and its tributaries the largest and most intact habitats and corridors for genetic exchange.

A green peacock snapped by the Wild China team on a visit to the Jiasa dam area (Image: Zhizhong Xi/WildChina )

Outdated view of development

The lawsuit has again highlighted the conflict between species conservation and hydropower development in Yunnan. Opponents of the Jiasa hydropower project say it reflects an “outdated view of development”.

Wen Cheng, chief scientist with Beijing Jinglang Environmental Technology, said that Yunnan is a national leader in biodiversity protection. For example, Yunnan’s forestry authorities funded four small reserves to protect the green peafowl, covering more than half the population of the bird on the Red River.

In September 2018, Yunnan was the first provincial government to pass regulations on the protection of biodiversity in the province. The province was also the first to issue lists of all species (2016), endangered species (2017) and ecosystems (2018). The new regulations put those efforts on a firmer footing.

The Jiasa project could damage the progress Yunnan has made on biodiversity and will have limited development value, said Zhang Boju.

The dam will exclusively serve two mining firms, Zhang added. Dahongshan Copper and Dahongshan Iron have signed deals with the hydropower company, which will see them buy 98% of the electricity.

The case also highlights the darker side of the hydropower sector. It is hard to build power networks in Yunnan’s mountainous terrain, and local demand for electricity is limited. Local governments therefore opt to attract polluting and power-hungry investors to utilise locally-generated electricity. Zhang describes that as “building for the sake of building”.

There are alternative ways to develop the local economy. Both the Xinping and Shuangbai county governments have stressed green development in local planning, aimed at attracting ecotourism and associated businesses. This is another challenge to traditional development approaches, such as dams and mines.

Feng Chun, a top Chinese rafting expert, said the area is ideal for the sport, and this would be a greener option for development.

Hydropower construction: the endgame

Hydropower companies are struggling to make a profit in China as electricity demand growth eases off, resulting in frequent wastage of power generation capacity. Statistics from Yunnan’s provincial grid showed an annual provincial demand of about 100 billion kilowatt hours in 2016 and about 90 billion kilowatt hours of power exports, compared to 300 billion kilowatt hours of annual generated capacity.

Grid access issues and price controls have left hydropower investors in Yunnan facing losses. In July 2016 Yunnan halted the development and expansion of medium and small-scale hydropower plants – those of 250 megawatts and less.

And after years of intensive hydropower development, the remaining locations have the biggest environmental risks. A provincial government document points out that 80% of potential hydropower resources have been developed. Those remaining are in environmentally sensitive areas, and issues have arisen with a number of existing hydropower plants. The local government is now at the point where it must reassess the environmental cost of hydropower development.

An uncertain fate

“The precondition for all conservation efforts is a full and complete halt to construction of the Jiasa hydropower project, and the removal of small hydropower plants already present in green peafowl habitats,” Zhang Boju said.

There are still uncertainties over the lawsuit, in particular, shifting official attitudes towards strict environmental measures. The central government has recently softened its approach to the enforcement of environmental rules. One company that built eight small hydropower plants in the Nanyue Hengshan nature reserve in central Hunan province was ordered to pay compensation rather than dismantle the dams. This approach may be copied in Yunnan. chinadialogue understands that courtroom arguments have focused on whether construction of the dam should be halted, or the builders ordered to pay for better environmental protection measures.

But Xi Zhinong, founder of Wild China, believes China’s “ecological civilisation” – the party’s long-term vision of a sustainable future – will remain the guiding principle in the courts. With construction of the Jiasa facility already halted, he thinks the court will not permit it to restart.

Zhang Boju says that NGOs using such lawsuits will force commercial investors and government departments to take a more cautious approach to development in biodiversity hotspots, with more attention given to site selection and feasibility studies.

However, Yunnan is still poor so improving living conditions and the local economy is a priority. Peng Kui, an expert on ecosystem conservation with GEI China, said the biggest challenge is improving conditions for local communities and ensuring sustainable development. Conservation measures such as protection of endangered species, setting ecological redlines and setting up national reserves must also help meet the needs of local people, he argues. Managing the relationship between those people and the land is key to successful conservation in the long run and to combat the impulse to develop at all costs.

This was first published on chinadialogue.net.