The view across the Huangpu River, looking over to the newly developed area of Pudong from the old quarters of Shanghai, is impressive.

Twenty-five years ago, this floodplain was dotted with farmers’ homes, cropland, old docks, and factory warehouses. Now the shining columnar skyline includes the second tallest building in the world, the Shanghai Tower, which was finished this year. Yet this imposing, hyper-modern vista hides the kinds of common, serious environmental problems that come with rapidly building a city from scratch in a short space of time.

Every year, seasonal tropical storms ravish the city, high temperatures hit life-threatening levels, and the few public green spaces available become uncomfortably jam-packed with locals.

Pudong, Shanghai. Image credit: Gonzalo Pineda Zuniga

It’s clear that Shanghai has some serious environmental problems — and one possible solution, which the city is embracing on a massive scale, is “urban greening”. Shanghai plans to plant 400,000 square meters of rooftop gardens in 2016 alone, an area roughly the size of Vatican City. By 2020, two million square metres of greenery will likely be added to the roofs and walls of Shanghai’s buildings.

New rules introduced in October 2015 also mandate that at least 50% of the roof area of all new buildings must be covered in plants.

Sticking plants on roofs seems to make sense, for the same reason that having parks in cities does — the plants help the city breathe, cleaning the air while at the same time offering a place of peace and relaxation for residents. They can even be used as sustainable urban farms, with knock-on effects for fighting climate change (and traffic) across a wider region by reducing the amount of food that needs to be shipped in from outside the city.

Numerous studies have shown that rooftop gardens filled with local, climate-appropriate plants — like the flowering and succulent Sedum, for example — have a net positive effect on dense, urban environments. Green roofs can improve a building’s energy efficiency, lessen the urban heat island effect that raises a city’s temperature, and help prevent flooding by absorbing stormwater.

All this seems to make urban greening a no-brainer, and architects around the world are churning out elaborate designs for new buildings with green roofs from Shanghai to Seattle. But there’s a catch — or, rather, there are lots of catches.

Urban greening concepts. Image credit: University of Greenwich, UK

“Unless there’s a density of green rooftops, say one every kilometre, then there’s not going to be much effect [in Shanghai],” said Dusty Gedge, president of the European Federation of Green Roof Associations.

“Also, rooftop gardens are only going to be part of the solution for cities. If anyone says they’re going to solve all your environmental problems, then they won’t,” he added. The problem is that all of those (considerable) benefits are often limited by the scope of integrated city planning policies.

Nannan Dong, a professor of landscape studies at Tongji University, points out that the new “vertical greening” rules that were approved in 2015 — and which mandate that 50% of new roofs get covered in plants — have come in too late. There are far fewer large-scale construction projects on the horizon than in previous years, and private developers are encouraged, but not obligated, to comply.

Dong explained: “For cities that have already been almost developed, you need to be ambitious. China is going in the right direction, but in many cities we have already urbanised. These policies needed to be in place 20 years ago.”

Shanghai plans to plant 400,000 square metres of rooftop gardens in 2016 alone, an area roughly the size of Vatican City

The challenges facing Shanghai can be applied across the world where politicians face regular criticism for not going far enough with environmental regulations, for fear of scaring off private developers with new building costs. Green roofs cost, on average, twice as much as a traditional roof—but they do last approximately twice as long, as they protect the surface beneath.

“They had the same problem in Germany,” noted Gedge. “They found out the hard way that you need to set the initial policy targets very high, because it’s very difficult to get it changed in ten years’ time when everyone’s got used to the idea.”

Across the world, from Los Angeles and Toronto, to Zurich and Copenhagen, major cities have been announcing the rollout of green-roof initiatives. By and large, European cities have legislated mandatory requirements, while US city governments have chosen to incentivise developers via tax breaks. Most urban planning departments base their codes of practice on comprehensive German guidelines, which were first published in 1982.

However, despite such a clear template, not every city is in the position to build roof gardens safely.

The main engineering issue is weight. If a large amount of soil and plants are added on top of a structure that’s not designed to support that much weight, the results can be catastrophic. In 2013, 54 people died in Latvia when a supermarket collapsed under the weight of the topsoil being added to its roof—it constituted the country’s worst peacetime loss of life in 60 years.

In countries with well-enforced building regulatory systems, and cooler climates, such problems pose less of a risk — buildings that can withstand heavy snowfall can usually also bear the weight of a garden. But in fast-developing countries with warmer climates, there’s more danger.

“Accidents are very possible,” said Dong. “In China, developers are expected to do a risk assessment, but it’s very easy for people to cut corners and assume, ‘Oh, it’s a new building, it’ll be fine to hold a garden.’”

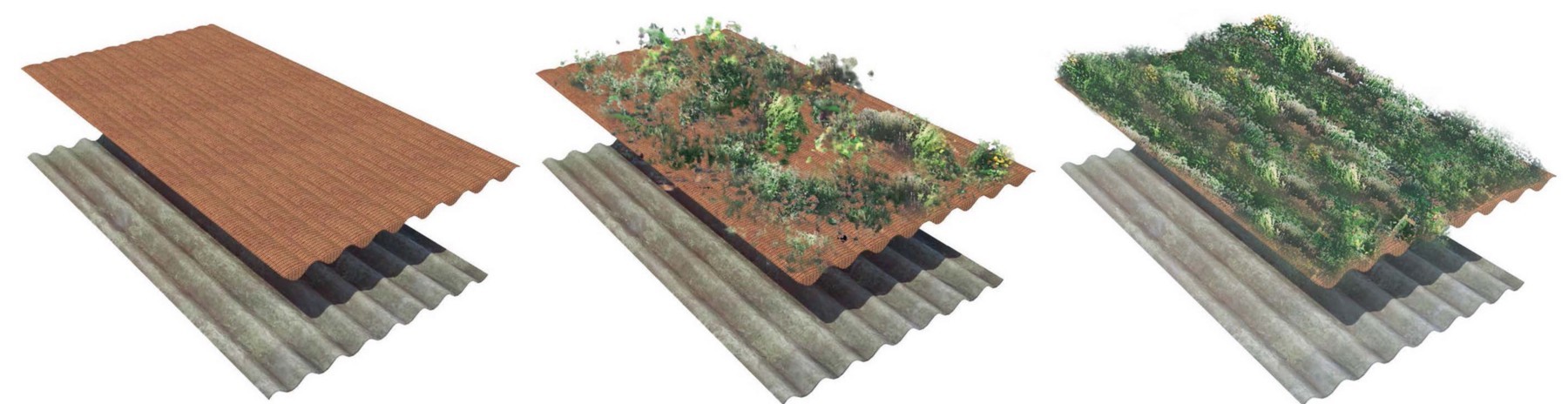

In order to retrofit buildings more quickly, and with a lower cost, architecture firms are experimenting with more nimble ways to build green roofs. Dutch architect Neville Mars has developed a low-cost roof mat, planted with seeds, that can be unrolled onto corrugated tin rooftops often found in city slums. These mats absorb much of the sun’s heat, making building interiors cooler, and transform into green coverage when it rains.

Low cost roof mats that could be deployed on a mass scale in developing countries. Image credit: Neville Mars

“We developed a prototype in India,” said Mars. “Our goal was to turn these bleak slum areas into green places. But you need a market-orientated approach. Even though we made this material very cheap, people still didn’t want to spend money. This kind of project either needs a sponsor or donor, or might be better suited to a more affluent community, perhaps in Latin America.”

Construction and implementation costs aside, there are also questions to be answered on the relative benefit of green roofs versus their alternatives. White roofs (or “cool roofing,” as it’s sometimes called) reflect sunlight away from buildings, making them cooler. In addition, they’re much cheaper to install and maintain.

“Part of the roof on my house is a white roof, designed to reduce indoor temperatures during the hot summer months,” said Ken Caldeira who heads a research lab at the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Global Ecology at Stanford University. “My basic view is where greening things makes sense, that is the way to go, but where green roofs are not practical and cooling is important, then white roofs make sense.”

Caldeira suggests that future research into green roofs could focus on low-weight, low-maintenance, low-water-consumption solutions. “With white roofs there are no issues with weight. It’s also easier to make a white roof than to put in plants and a watering system. And not every city has an abundant supply of water for roof gardens,” he said.

However, Caldeira acknowledges that when it comes to urban planning, the environment is “not all about global warming.”

“I would rather live in a city that is one degree warmer but full of greenery than a city that is one degree cooler but full of austere white surfaces,” he said. “Most people would prefer a downtown full of trees than brightly reflective concrete.”

This article was originally published on How We Get To Next.