China is the world’s largest timber market and sources wood from more than 80 countries. But, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a London-based NGO, it is also the world’s largest importer of stolen wood.

On a recent trip to Mozambique, in southern Africa – where China consumes more than 90% of the country’s timber, up to half of it logged illegally, according to the EIA – it became clear that China is being seen not only driving illegal deforestation, but also helping with its potential solutions.

More than half of Mozambique is covered by tropical forests, but the almost 3,000-square kilometre Gilé National Reserve, in coastal Zambezia Province, has one of the most pervasive illegal logging problems in the country.

There, pau ferro (Libidibia ferrea), a protected exotic tree, is at risk of extinction because of high commercial demand for its wood. Jose Dias, the reserve’s warden, told me it is extremely rare to find pau ferro outside such protected areas.

A trip to the reserve let me see first-hand how illegal logging works in Mozambique. On arrival, I saw several rusty trucks parked at the entrance, loaded with huge pau ferro logs. These had been seized by rangers, after smugglers had unsuccessfully tried to steal them from the reserve.

Despite being a habitat for wildlife, including lions, leopards, elephants, buffaloes and more, the reserve attracts few tourists due to a lack of infrastructure.

But rangers have their work cut out trying to counter the many smugglers across the vast reserve. Since 2012, they have stopped a total of 58 trucks and 10 tractors of illegal wood. “Many more are not caught,” said Dias.

In a report from March, Dias described this illegal logging as “organised crime”, involving collusion with police, officials, transport checkpoints, community leaders and sometimes even staff at the reserve.

The logger

Before travelling to the reserve, I met in the provincial capital, Quelimane, with Zambezia’s head of land, environment and rural development, Antonio Osvaldo Paqueleque.

A newcomer on the job, he claimed to know little about the area’s timber sector. But his department were more helpful, suggesting I speak to Jorge Bing: the province’s only Chinese owner of forestry concessions, two of which border the southeastern edge of the reserve. Rangers had once captured eight trucks packed with pau ferro “of reserve quality” leaving Bing’s concession.

Bing has lived in Mozambique since 1973. A well-known and controversial figure in the province’s business world, he has been involved in logging for almost two decades and owns seven timber factories. His family also owns houses and convenience stores in the city of Quelimane.

Jean-Baptiste Deffontaines, a French technical advisor from the reserve, described Bing as one of nine illegal loggers “known around the reserve.” Annwaudo Nawea, a timber producer from Mucucune area, near Bing’s concession – who admitted smuggling pau ferro from the reserve — described him as “bad person” who “doesn’t pay in time.” Another local concession owner told me he was a “tough man to deal with”.

But Bing himself, a bald man in his early fifties, told me matter-of-factly that he wasn’t interested in the timber business anymore.

We met in a local bar in Quelimane run by one of his high-school classmates, a local Mozambican. Unlike many other Chinese in Mozambique, Bing feels very settled in the country. “My ex-wife, from Mainland China, wanted me to leave Mozambique,” said Bing, a Taiwanese. “But how could I? Everything I own is in Mozambique.”

As for the timber market, “the entire sector is corrupt,” he acknowledged, “and there’s no space for legal work.”

“Because illegal is the norm, the reserve is in chaos. Villagers, and even the guards in the reserve, all want to sell pau ferro.” He showed me pictures of pau ferro from within the reserve and from outside the reserve, to show the difference in quality. “The reserve has the best woods and villagers are more than happy to bring them to us.”

“Why would anyone say no to logs of the best quality?” He asked me.

Truck carrying illegal Pau-Ferro logs in Gile national park, captured by rangers. (Image by Estacio Valoi)

The minister

Celso Correia, Mozambique’s minister of Land, environment and rural development, said he had never heard of Jorge Bing, but he knew the situation in Gilé well.

“In early 2015 when we first came to office, we decided to conduct an analysis of the current situation,” said Correia. He had WWF Mozambique and some local NGOs carry out a survey, which found “more than 50% of current concessions shouldn’t be operating.” Following the survey, Correia imposed a two-year ban on all new concession licenses.

“We are cleaning the house now,” said Correia. “We just proofed a new Forestry Law which is going to the Parliament this year. We passed a new Conservation Law too. For people involved in illegal logging – if they’re caught, they’ll go to jail for 15 years. Before, people used to just pay a fine.” He also banned all logging of pau ferro from January 2016.

The challenges of deforestation in the country weren’t mainly from logging but from agriculture, and “charcoal production by local communities,” said Correia. “We need to have a forest that’s sustainable and we need to have a market,” he added.

For the country’s environmentalists, this was too little, too late. The new rules came in just as Chinese demand softened, as the economy slowed and the anti-corruption drive dissuaded Chinese buyers from investing in ornate, showy furniture pieces made from tropical hardwood.

Still, Correia argued that weaker Chinese demand for timber had made it easier to push through these tougher laws. With the wood price down, he said, “there’s less pressure”.

This was not the first time the Mozambican government had tried to act on logging. As early as 1999, the government had listed eight species, including pau ferro, as first-class hardwoods banned from export in log form.

But the partial export ban was ineffective. As the sustainable trade specialist Anne Terheggen put it, the ban “did not produce the anticipated benefits of value creation, additional employment and sustainable forest management.”

As China effectively remains the country’s sole market for timber, the domestic industry has little room to manoeuvre. There is little processing locally and much of Mozambique’s tropical hardwood is exported to Chinese buyers as logs.

Corruption is widespread. Bing described payments being made all the way up the chain, from local loggers to high-level officials. EIA concluded in a report: “Mozambique provides a stark illustration of the chronic failure of forest management which ensues when China’s insatiable demand for logs converges with weak law enforcement and corruption.”

Still, Correia was confident. “After we organise the industry,” he told me in his Maputo office, “investors from China, Europe and America will see then we have a regulated market and that we have good system. But to build the wood industry in Mozambique, it will take at least up to 10 years.”

The factory manager

Late last year in Beira, the capital city of the central Sofala Province, Governor Maria Taipo visited three Chinese timber factories unannounced.

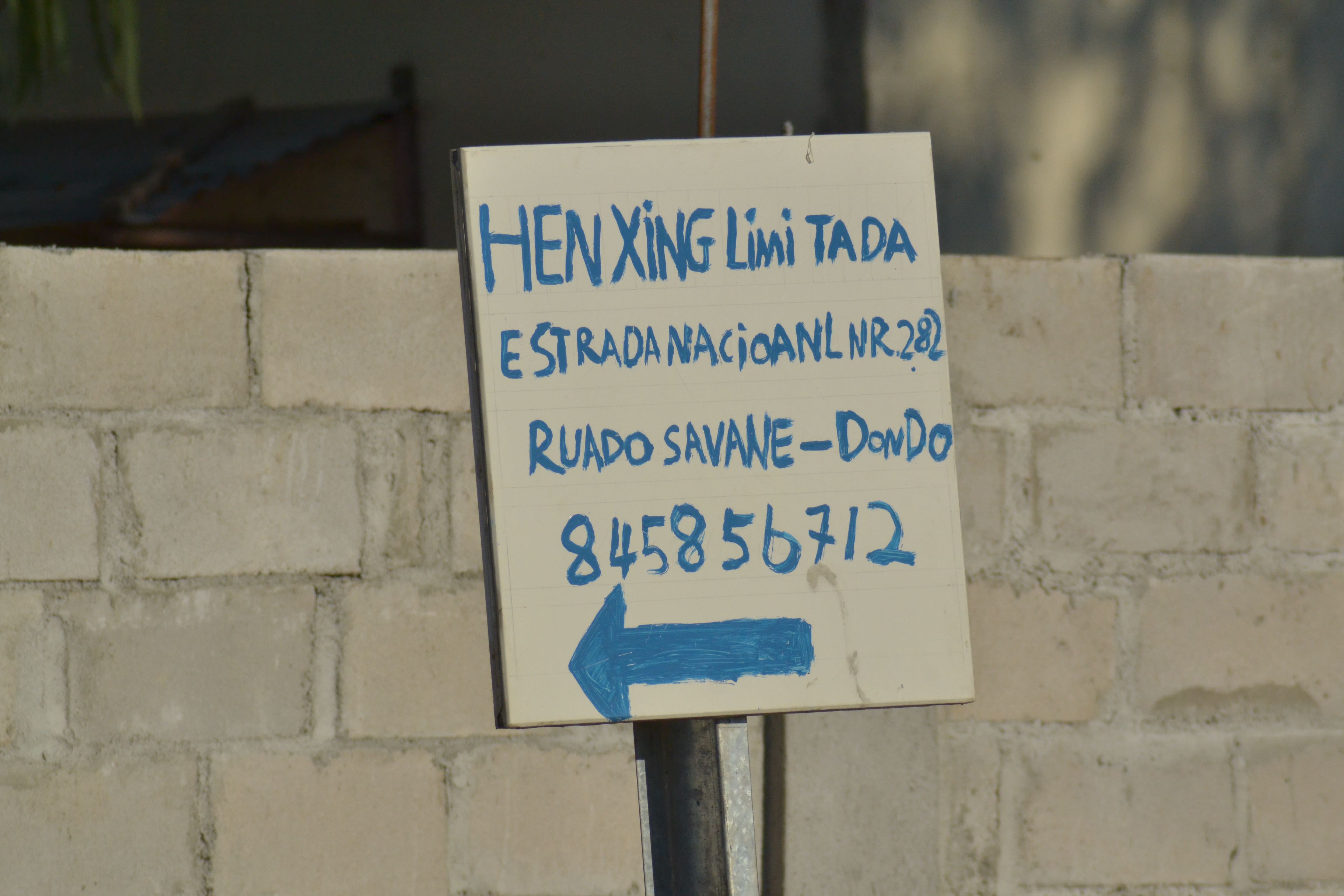

From a list of labour violators compiled by the local labour department, Taipo had identified three factory owners she wanted to take by surprise: Heng Xin, Ming Fan Shan and Didi Madeiras.

Jaime Chicamisse, head of the provincial labour department, said they had already issued suspension notices prior the governor’s visits, “but they did not comply.” Regarding Heng Xin, Chicamisse told me: “It was difficult for us to talk to the company; they often hire some local middleman to handle us.”

The Governor’s visit had the desired effect. Taipo’s order for suspension was complied with.

I managed to get access to Heng Xin’s factory, a few months after its suspension had been lifted. There I met Lin, the factory manager, who declined to give me his full name while the owner was away in China.

Lin said it was one of the biggest factories in the region, employing around 100 local workers, mostly paid the official minimum wage of MT3,298 (US$67 / 447 yuan) a month. “The governor’s visit was just a stunt for the media,” he said. “Our company’s situation was not different from others.”

The labour violations described by Taipo included a lack of contracts, uniforms, changing rooms and even toilets at the factory.

Surprisingly, Lin and his Chinese colleagues spoke to me freely, painting a prejudiced picture of the local workers as “lazy”, feckless and drunk. “They are different from Chinese workers,” he said.

But when it transpired my fixer, a Mozambican investigative journalist, was carrying a camera, the interview turned sour.

We were put on the phone with the company’s Mozambican lawyer, who suggested we could only talk to a few workers picked and prepared by Lin.

Still, at the end of the day a large group of workers were waiting for us outside the factory gates. They clamoured to tell us that they couldn’t take days off, even for family funerals; that they were forced to work when sick or injured; and even that workers had been beaten for complaining.

Hen Xing is one of the three Chinese timber companies that have been temporarily suspended by the local authority. (Image by Estacio Valoi)

The solution

Correia, the minister, said the solution to the sector’s problems would also come from China. “As we organise the sector,” he said, “more serious Chinese companies will decide to come”.

Zheng Fei may represent one such example. In cooperation with WWF China, Zheng plans to build a privately owned “Sino-Mozambique Forest Resource Ecological Zone” in the northern province of Cabo Delgado.

Zheng, who arrived in Mozambique in 1998, owns a timber company called Feishang, in Pemba, the capital city of Cabo Delgado. He is familiar with the country’s timber sector and its problems.

“It makes sense that Mozambican people blame Chinese timber companies,” Zheng said, “as we did not bring any real benefits to the locals.”

According to Zheng, the roughly processed timber required by the Mozambican government was not favoured by Chinese furniture manufacturers. “That’s why smuggling logs became popular.” His ambition is therefore to relocate the entire value chain to Mozambique.

“Cheap labour and natural resources are already here,” Zheng said. “Manufacturers in China just need to step in and my industrial zone is going to be their choice.”

Two days before I met Zheng, his general manager Zhou Ming took me to the Ecological Zone, in Mocimboa Da Praia, 300 kilometres north of Pemba.

The 100 square kilometres of land – which Zhou explained had been acquired from villagers, who would be compensated, with the support of the local government – were still largely unused.

There was a single sawmill and wood-drying plant, but they weren’t in operation. There were a few local workers. Two Chinese workers tended a flourishing vegetable garden while cooking an unappetising lunch made from the meat of a pangolin, an endangered species.

Zhou, in his late 30s, is fluent in Portuguese. He seemed content and settled and had married a local woman of Indian origin. “It’s not possible to bring a wife here from China,” he said. “Girls don’t like Africa.”

The two newly arrived Chinese workers were less situated. A few weeks earlier, someone had cut the wire fence around the factory and stolen a few planks. Scared that local villagers might rob them, they didn’t go out alone.

According to Zheng’s ambitious plan, the Ecological Zone and related service will expand to 300 hectares by 2020, with an investment of US$200 million (1.3 billion yuan), creating 12,000 job opportunities up and down the value chain, processing wood for furniture and making as much use as possible of any waste.

Wang Lei, who works for WWF China – and provides technical support, as part of a programme encouraging Chinese entrepreneurs to act lawfully in Africa – was hopeful about the project, but told me the major challenge was that the plan relies on private investment. This “means if the investment is not realised, then the future of the project will be unpredictable.”

Still, regarding environmental problems in Africa, Wang asked pointedly: “Can we change these companies and make sure they act according to law without changing the local governing environment?”

“Many Chinese entrepreneurs invest in Europe and the United States” without breaking the law, said Wang. “Why are so many Chinese conducting illegal business here in Africa?”

Additional Reporting by Estacios Valoy.

The investigation is funded by non-profit organisation GEI (Global Environmental Institute).