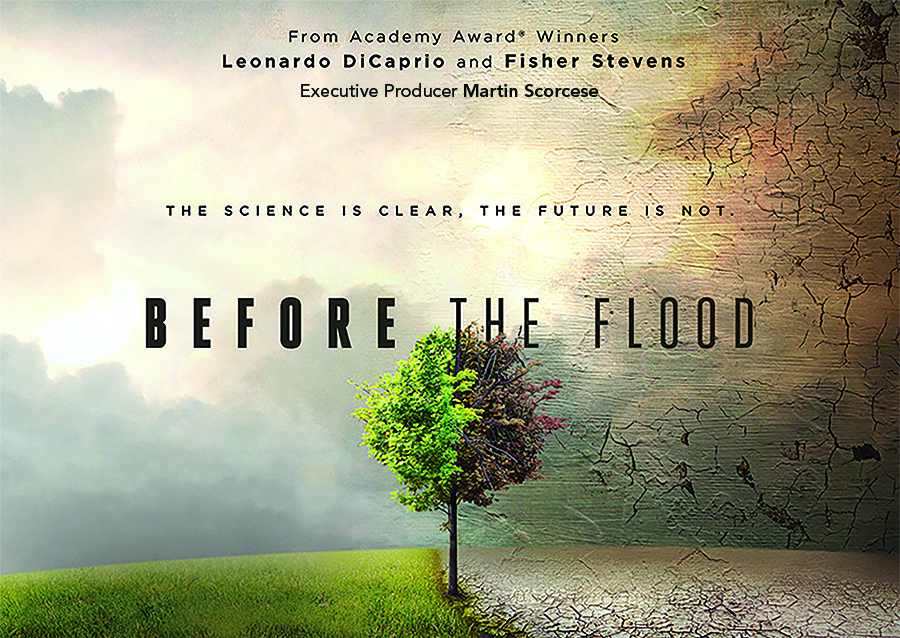

Leonardo DiCaprio’s latest documentary film Before the Flood is a plea for urgent action on climate change. It’s been watched a record-breaking sixty million times and is regarded by some as the most powerful climate change film since An Inconvenient Truth was released in 2006. Indeed, some media outlets have even referred to it as the new An Inconvenient Truth.

Given the strong tradition of climate science denial in America’s Republican Party, and Donald Trump’s own refusal to accept climate change, the film’s release date was politically timed to coincide and influence the outcome of the US election. Initially available to watch for free on the National Geographic website, the viewing window closed the day before the election was held.

Reflecting the times

Before the Flood is like a sequel to Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth, which highlighted the risks of climate change to a mainstream US audience. Both films essentially tell the same story, take the same positions and even feature some of the same people. DiCaprio acknowledges that Gore has been his guide on climate change issues; the two men even sat down for a long conversation on the topic during Gore’s vice-presidency.

A decade on from the original film, these two heavy-going documentaries inadvertently serve as milestones for how the debate on climate change in the US has shifted and action to address it changed. The election of Barack Obama in 2008 brought about a favourable shift in US policy on clean energy and climate change. But let’s not forget that ten years ago, China and the United States were at loggerheads on climate change. Nowadays they are working together closely and taking the initiative globally on climate change action.

In the past decade, the warnings about how climate change would impact countries and communities have started to be borne out in more severe and unpredictable weather events. However, there has also been a rapid shift towards renewable technologies such as solar and wind. Viewers of Before the Flood are shown that effects of climate change are happening but can take comfort from the fact that a global response to go low carbon is gaining momentum and beginning to make a difference.

In contrast, An Inconvenient Truth didn’t have much to say about how to solve the problem of climate change. To be fair, at that time wind and solar energy comprised only a small portion of global energy production and forecasts for the adoption of these technologies have since proven extremely conservative. Watching the two films in succession, it’s hard not to be amazed by the global changes that have taken place over the past ten years.

A message of hope

One of the saddest things about An Inconvenient Truth is watching Gore reiterate his climate change message to the public. Not long into the film, following a series of shots showing climate disasters and a busy Gore travelling from place to place giving lectures, we see him in the backseat of a car, calm and determined, his laptop open, tweaking his speech. In the voiceover he calmly says, “I’ve been trying to tell this story for a long time and I feel as if I failed to get the message across.”

One shot is repeated over and over: Gore, on his own, wheeling his suitcase as he hurries to give a lecture. The former vice president and presidential candidate for the Democratic Party appears determined but he also cuts a lonely figure.

This is in sharp contrast to DiCaprio in Before the Flood. In a series of lively scenes the Hollywood star is met by a host of scientists, politicians, and social activists who take him to an array of majestic natural landscapes. He talks with polar bear hunters in the Arctic Ocean, gets close to red orangutans in Sumatra and flies over melting glaciers in a helicopter. While Gore’s lonely figure conveys the environmentalist’s plight of getting the message heard, DiCaprio’s experience seems more like an adventure holiday across spectacular locations affected in some way by climate change.

Global problem, local effects

A key focus in An Inconvenient Truth is how climate change will affect the US. It shows the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and uses landmark buildings to illustrate the effects of rising sea levels. DiCaprio’s film takes a more international outlook. Although it mentions municipal funding for flood control in Miami Beach, most of DiCaprio’s time on camera is spent globe-hopping. He appears in Beijing’s hutong district, Delhi’s slums, on some ice in the Arctic Ocean, and even at the Pope’s residence in the Vatican.

A consequence of this global approach is that, unintentionally, the film could leave viewers with the impression that people and politicians everywhere are in agreement about the urgency of climate change, and that simply getting them to act on it is the challenge. However, Donald Trump’s election victory and his history of climate change denial show that agreement on climate change is far from universal.

Ahead of the 2016 US presidential election, New Yorker journalist George Packer published an article that included an interview with Larry Summers, the former US Treasury minister. Summers described his numerous visits to countries in Africa and Latin America, detailing his involvement in efforts to alleviate poverty.

“I don’t think I ever went to Akron, or Flint, or Toledo, or Youngstown,” admitted Summers. These are US towns and cities that also have high levels of poverty, and populations that feel abandoned by those in power.

The elitism implicit in this global perspective weakens the moral force of DiCaprio’s film. As Gore reiterates tirelessly in An Inconvenient Truth, the most difficult aspect of educating people about climate change is overcoming the obstacles to people’s acceptance. If Before the Flood included more material addressing the concerns of middle and lower class US workers it would provide a more empathetic portrayal of dealing with the social implications of climate change.