Demand for plastics is expected to double in the next 20 years. But failure to address the way we handle waste could mean that by 2050 there is more plastic in the oceans than fish.

See: Marine plastics threaten the future of our oceans.

We spoke to Rob Opsomer, lead of the New Plastics Economy initiative at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, who says it’s time to tackle the root cause of plastic pollution and move towards a circular approach by which plastics are designed to stay in the economy, and out of the environment.

chinadialogue (CD): The public discourse around the environmental damage and health risks of plastic waste is growing. But so is demand for plastic products. By 2036 this is expected to double, according to a report from the World Economic Forum. Why as a global society have we become so addicted to plastics?

Rob Opsomer (RO): We should start by acknowledging the many benefits that plastics bring to our lives: they are lightweight, versatile and cheap; they help protect our food and make our cars lighter. They combine unrivalled functional properties with low cost and so have become the ubiquitous workhorse material of modern production.

CD: So while plastics have many benefits, the safe removal of plastic products, in particular packaging, has become a burden to society as most ends up in landfill or marine environments where they harm wildlife and ecosystems. Why is disposal such a key issue?

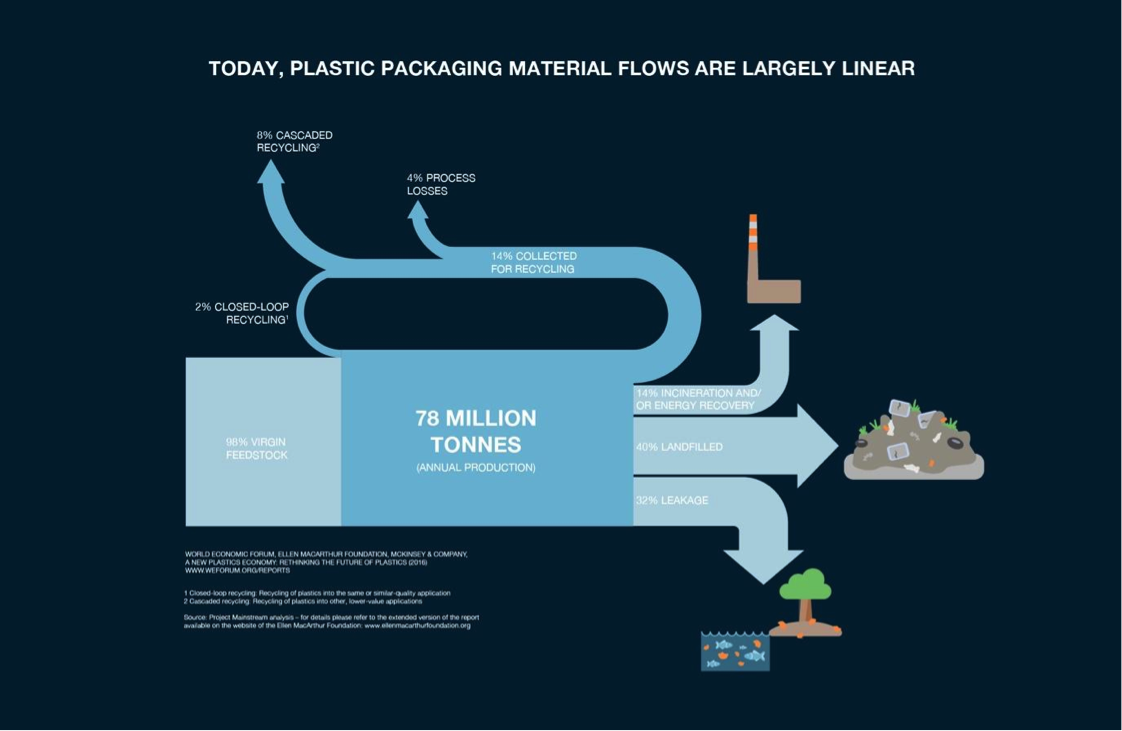

RO: Plastic packaging makes up 26% of the plastics market. Companies go to great lengths to design and create plastic packaging items, but most of them are used just once before being thrown away. Forty years after the launch of the first universal recycling symbol, only 14% of plastic packaging is collected for recycling globally, and only 10% effectively gets recycled. A staggering 32% ends up in the natural environment, often on beaches and in rivers and oceans. This represents a loss of USD 80-120 billion per year to the global economy.

If improvements were made both to packaging design and to the systems for managing packaging materials after use, 50% of plastic packaging could be profitably recycled.

Yet a total of 30% of plastic packaging (by weight) is currently – by its very design – destined for landfill, incineration or energy recovery. These everyday items, such as sweet wrappers, shampoo sachets and fast food packaging, are made to be used only once and cannot be recycled economically. Our initiative will launch an innovation prize in May 2017 to mobilise designers, entrepreneurs, scientists and academics to rethink the plastics system and design solutions that keep plastics in the economy and out of the environment.

CD: If leakage stems from problems in the supply chain then what are businesses, which profit from making plastics, doing to address it?

RO: Several countries around the world, including China (the world’s biggest producer of plastics, followed by the European Union) have limited or banned the use of plastic bags, and the European Commission is aiming to publish a strategy on plastics by the end of 2017 as part of its Circular Economy Action Plan.

Unilever, one of the seven Core Partners of the New Plastics Economy initiative, has announced it will make all its plastic packaging reusable, recyclable or compostable in a commercially viable way by 2025.

CD: How can industry leaders, like Unilever, help close this loop?

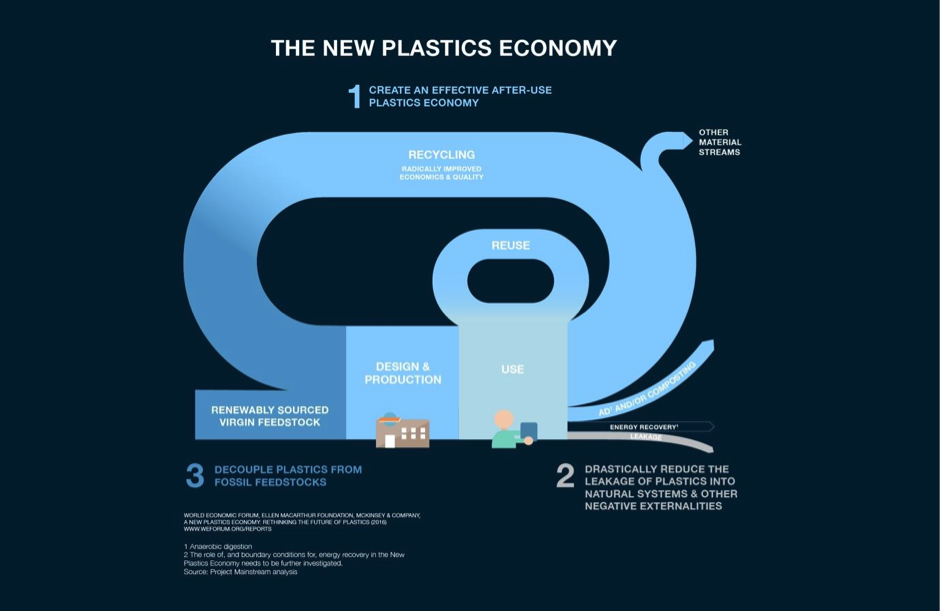

RO: Industry players need to collaborate on creating an effective after-use plastics economy by improving the economics and uptake of recycling, reuse and controlled biodegradation. This is the cornerstone of the New Plastics Economy and its first priority.

Innovation in how we design, use and recover plastic packaging is key to drastically reduce leakage of plastics into natural systems (in particular the ocean), and to decouple plastics from fossil feedstocks by using renewable feedstocks, dematerializing, and reducing cycle losses.

CD: What are you doing to push this agenda?

RO: Our initiative brings together a broad group of more than 40 leading companies, cities, philanthropists, policymakers, designers, academics, students and NGOs. The US$10 million, three-year initiative aims to build momentum towards a system redesign based on circular economy principles. Our latest research outlines an action plan for industry players to transition towards a circular economy for plastics.

CD: Aside from the business community, what can national policymakers do to make solving plastic pollution an economic opportunity?

RO: Over 20% of plastic packaging could be profitably re-used, for example by replacing single-use plastic bags with re-usable alternatives. This has often led to large decreases in the use of single-use plastic bags. China, for example, reported a 66% drop in use, equivalent to 40 billion plastic bags, after introducing a ban in 2008.

Next to creating the enabling conditions for reusing packaging, policy makers can support uptake in recycling and innovation towards a circular economy for plastics.

You can access more information on the New Plastics Economy initiative here.