Depending on who you listen to, China is either on the cusp of revolutionising world energy storage and electric vehicle (EV) markets, or in the throes of upheaval.

Of course, the reality is a bit more nuanced. Some of the issues experienced by the electric vehicle sector in the last few months have resulted from an urgent need to reform the country’s vehicle subsidy programme. But going forward, China can learn a few things from other countries in the design of its programme that will boost the market while limiting the scope for cost overruns.

China is already a global leader in EVs and battery manufacturing. In May 2014, President Xi Jinping declared that new energy vehicles would be a path for China to become a strong automotive manufacturer.

This was more than wishful thinking. From 2013 to 2016 the Chinese market leaped from under 20,000 new energy vehicles per year to more than 350,000 electric cars and over 115,000 electric buses, accounting for 46% of worldwide electric car sales and a whopping 95% of electric bus sales.

Sales have been boosted thanks to subsidies of up to 50,000 yuan (US$7,000) for a passenger car, and promotion of EVs for taxis and buses. Beijing is the latest city to announce that its 67,000 taxis will shift to EVs. The central government also has plans to apply an EV quota on all automakers.

Motives

China’s EV push over the past few years serves several policy goals. The first is an industrial strategy aimed at capturing markets for industries of the future. China has identified EVs as a technology that was “bypassed” by foreign automakers. By moving on this market, it can benefit from its ability to rapidly scale battery and EV manufacturing.

The second goal is to limit oil imports. Car ownership and driving are growing rapidly, and China, which imports 65% of its oil, is now the world’s largest oil importing country.

Pollution is a third driver. Transportation is a major contributor to urban air pollution and rising rapidly, though the majority of transport particulate and NOx (nitrogen oxide) emissions come from diesel trucks. EVs may seem like a counterintuitive solution given China’s coal-based power grid, but various studies have shown that switching to EVs produces a significant air quality benefit. And in the future, EVs could be charged when a surplus of clean energy is available.

Subsidy problems

But China’s subsidy programme has encountered problems. Last year the government began fining and punishing companies that had received subsidies illegally, including at least one that had never even made electric vehicles.

As EV sales rocketed upward in late 2016, the cost of subsidies started to look excessive. There has also been criticism about the quality of the subsidised cars and batteries.

The government decided to review the system. In January – always a slow month for EV sales – it announced that manufacturers would have to re-qualify in order for customers to continue to receive subsidies. EV sales plummeted to just over 6,000 per month, which is 60% lower than the same month the year before.

The adjustment is already looking like a short-term blip though. As companies re-qualified in February, sales have returned, and the government hopes for full-year EV sales to rise up to 40%, easily surpassing the impressive 2016 total.

Quality counts

Chinese EV manufacturers are focusing more on quality, too. While many of the leading domestic EVs are tiny “city vehicles”, bigger sedans and crossovers with decent electric range are on the way. This transition is necessary: surveys show that Chinese car buyers have similar range and performance aspirations to those in the developed world.

To satisfy the demand for longer range vehicles, the country needs to upgrade its battery technology know-how. China has opened up subsidies for lithium-ion batteries with the nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) chemistry, which offers greater performance than lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) used in first generation EVs.

As for an EV quota applied to automakers, policymakers have considered revising the scheme after several automakers, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, raised concerns. A revised regulation is due out later this year.

China is already learning from experience and from subsidy programmes elsewhere that no support scheme is perfect. Also, that small tweaks in how subsidies are designed can produce major shifts in outcomes, and sometimes work against a policy’s original goals.

But as China pursues rapid adoption of electric vehicles what specific lessons can it learn from the US, which has been chasing EVs for much longer?

Find your balance

Perhaps the most important lesson from EV subsidy programmes in the US, as well as various efforts worldwide with feed-in tariffs to promote renewable energy, tax credits, quotas, tradeable credits, non-monetary subsidies like free parking or special lane access, and other schemes, is that policymakers have to strike a balance between many competing goals.

One goal is providing market certainty through policies that will remain in place for long enough to enable carmakers to invest in production and new technologies. But flexibility is also necessary: programmes have to evolve to prevent companies gaming the system or respond to technology/market changes that are slower or faster than expected.

Subsidies must promote choice, not stifle it

Even California’s zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate, which is widely credited with driving the state’s domination of vehicle electrification in the US, has faced heavy criticism. The problem is that almost half the nation’s EV registrations are for California-based Tesla vehicles, leading some to call the state’s zero-emissions vehicle credit-trading programme a “Tesla support scheme”.

In addition, designers of the ZEV mandate gave extra credit for such innovations as longer EV range and hydrogen fuel cells. However, battery technology improved faster than policymakers anticipated, helping Tesla’s longer-range EVs to dominate the domestic market.

Carmakers can pay Tesla to acquire credits and thereby meet the ZEV mandate even though they are producing fewer EVs than the state originally targeted. A Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) study showed that by 2025 carmakers can meet the zero-emission mandate by producing ZEVs that total only 6% of annual vehicle sales in the state, less than half the state’s target of 15%. So the policy appears to be falling short, in part due to an oversupply of ZEV credits.

Takeaway 1: While California’s programme encouraged innovation and flexibility, the design resulted in the state missing its targets for emissions reductions and total new energy vehicle sales. In retrospect, by allowing a single company to dominate the market, the original ZEV mandate design gave consumers fewer EV choices.

Avoid penalising early movers

The federal tax credit for hybrid and electric vehicles has faced design issues as well. The federal government offers up to US$7,500 per EV, depending on the size of the battery pack, and the subsidy begins phasing out after a carmaker sells a cumulative 200,000 plug-in vehicles.

This design ensures that the total cost to the government is limited while encouraging carmakers to gradually make EVs more cost-competitive with conventional cars.

But critics complain that the programme gives no credit for early action. In fact, it even penalises early-adopters: Tesla, GM, and Nissan, which pioneered the plug-in revolution in the US, will be competing subsidy-free against latecomers that are still subsidised.

In a way, this is the opposite problem from California, where the early-mover Tesla arguably received an unfair advantage.

Takeaway 2: A flat per-vehicle subsidy capped after an automaker sells a certain number of EVs helps limit costs but doesn’t reward first-movers or innovation.

Beware favouring domestic companies

Another consideration for China is the role of foreign competition. As Tesla shows, there are pros and cons to giving domestic companies a leg-up. Many California customers may feel a different approach to subsidies would result in more choice and faster emissions reductions.

In China’s case, there is strong consumer demand for foreign vehicles, and now that many leading automakers are shifting to EVs, foreign carmakers are likely to have many high-quality, globally-competitive EV models available in China by 2020.

Short-term programmes that favour China’s fleet-footed automakers have produced a huge burst in EV manufacturing, but can this be sustained when the vehicles have to compete worldwide against global leaders that plan vehicle production on five-year cycles?

Furthermore, the introduction of EV quotas for domestic manufacturers before they are ready with quality products could freeze foreign players out of the market in the near term, but in the long term could hold back domestic carmakers from producing higher quality EVs that could compete with those likely to emerge from the likes of GM, Ford, BMW, and Volkswagen.

Takeaway 3: A scheme with staying power that rewards a mix of vehicle and battery characteristics might be more attractive than a flat per-automaker EV quota and per-vehicle or per-kWh government subsidy.

China may also want to consider a subsidy that declines automatically as certain volume goals are reached, instead of one based on fixed dates. When subsidies expire or decline at a set date, such as on December 31, this can create an artificial boom-and-bust cycle and result in unpredictable programme costs that spiral out of control – as happened with renewable feed-in tariffs in many countries.

Takeaway 4: Schemes in which subsidies decline when volume targets are met have proven effective in California for promoting solar and energy storage, and could work for EVs in China as well.

No subsidy scheme is perfect. China’s EV plan is moving rapidly and likely to contribute to scaled-up battery manufacturing and know-how and improvements to air quality and reduced oil consumption. Whether China’s policies will make the country the dominant EV player worldwide remains to be seen, but I wouldn’t bet against it.

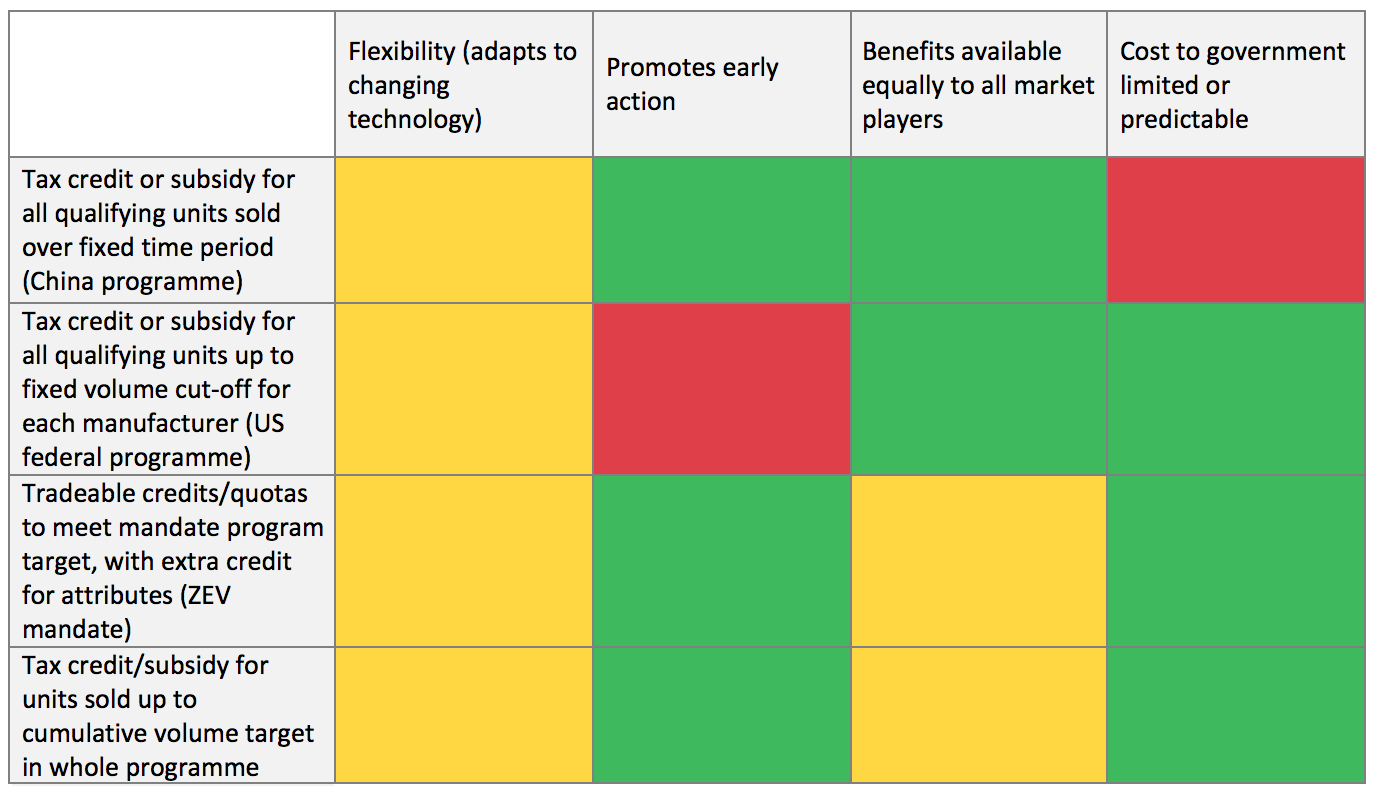

Attributes of various EV policy designs, based on US and China policies

Green indicates a positive attribute, red a negative attribute, and amber is neutral. Source: Author