The launch of China’s national emissions trading system (ETS) last December marked a major milestone in global efforts to deliver on the Paris Agreement. The addition of China’s ETS means that over seven gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent – roughly 15% of global emissions – are now covered by carbon markets.

China has the world’s biggest power sector and is developing globally significant industries so implementing a successful ETS is a daunting endeavour. However, our latest report by International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) on worldwide emissions trading highlights some lessons of older schemes from which China’s ETS architects can learn.

Since the first system started in 2005, a lot of experience has been accumulated in the design and operation of carbon markets. This is also the case in China, which has been operating pilot carbon markets in recent years, providing policymakers with important lessons to draw on in the design of a national system.

Perhaps the most important conclusion from more than a decade of global ETS experience is that emission trajectories are hard to predict, and circumstances can change in unexpected ways.

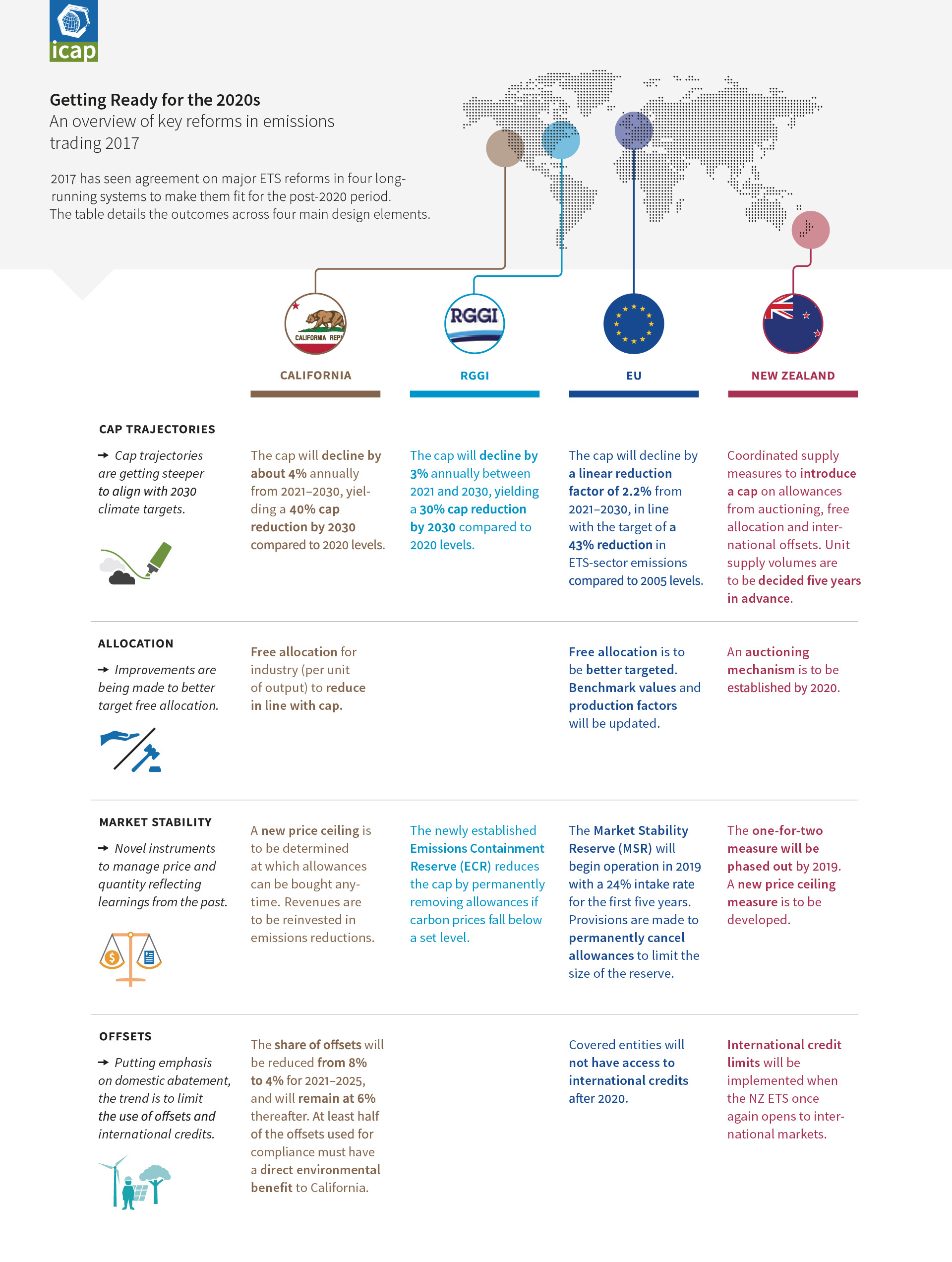

This means that carbon markets must strike a balance between stability and adaptability to changing circumstances. This is why the recently concluded reforms in some of the longest-running systems to get these systems ready to meet declared emissions targets in the 2020s are so significant (see infographic below).

Credible and stable pricing

For carbon markets to incentivise investment in low carbon projects, a credible and reasonably stable carbon price is required.

Unfortunately, predicting carbon emissions and hence the demand for allowances is challenging. As a consequence, all long-running systems have introduced and refined how they manage allowances to emit carbon dioxide by adjusting the price or quantity of allowances based on market conditions.

This helps to prevent price hikes, avoid the over-supply of allowances, and help increase ambition automatically when climate mitigation appears easier than anticipated (RGGI, EU ETS). Similarly, minimum prices at auctions are a commonly used tool to stabilise prices and limit the number of new allowances when there is an excess in the market (California, Québec, Ontario, RGGI).

Chinese pilots have also experimented with market stabilisation measures. For example, Beijing has set a price floor (20 yuan) and ceiling (150 yuan) for allowances. Together with relatively stringent allocation methods, this has led to the highest average price among all pilots in Beijing of 38.5 yuan between 2013 and 2016, 46% higher than the average of all seven pilots together.

Phasing out the free allocation

Almost all carbon markets, including those in China, have relied on the free allocation of allowances in the beginning but the share of these allowances needs to go down over time to achieve ambitious reductions in carbon emissions.

A move from free allowances to the auction of permits is beneficial because it helps establish a clear market price. This is why established systems like the EU ETS have reduced free allocations from nearly 100% to about 40%, with the remainder allocated through auctioning. A similar share of auctioning exists in the Western Climate Initiative, a trading scheme that includes American state California and Canadian provinces Québec and Ontario. The Korean ETS, one of the world’s youngest schemes, will start to auction a share of its allowances from 2019.

Chinese climate and energy expert Zou Ji argues that China should follows these examples in the medium to long-term. China already has some experience to draw on, such as the auctioning scheme from the pilot market in Guangdong province.

As the world’s largest emitter and a key emerging economy, China’s path towards building a successful national carbon market will be of global relevance. If China can get it right, then it will serve as a guide and inspiration for planned emissions trading systems in emerging economies.