For the group of Tibetan youngsters, it was a rare opportunity to see what life is like on the lower reaches of the river known as the Lancang in China, and the Mekong elsewhere. Hailing from Qinghai province, near the source of the Lancang, the group was part of the third Youth Innovation Competition on the Lancang-Mekong Region’s Governance and Development (YICMG), which started on January 27 in the Lao capital of Vientiane

Since 2016, when the first youth exchange took place, more than 100 university students from the six Lancang-Mekong countries of China, Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Cambodia have participated.

Wang Zeyun, media officer from the Yushu government in Qinghai province, which hosted the previous two events, said the government advocates “drinking water from the same river and building a community of common destiny”.

Wang added that, “The event is intended to unite young people’s wisdom and power, and provide support for the sustainable development of the six countries in the Mekong River region.”

The cultural and educational exchange programme, sponsored by the Chinese government and organised jointly by the six riparian countries, has been included in the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) Framework, an initiative started by China in 2015 to facilitate multilateral cooperation and regional integration.

Mekong-Lancang leaders sign deals at the second summit in Phnom Penh (Image: KT/Chor Sokunthea)

Lancang-Mekong cooperative mechanism

The world’s 12th-longest river, the Lancang-Mekong meanders over 4,909 kilometres from its source – considered to be the Lasagongma Spring in Yushu – until it empties into the South China Sea via the Mekong Delta. Over 60 million people depend on the river and its tributaries for food, water, and other aspects of their daily lives.

Over 60 million people depend on the river and its tributaries for food and water

Premier Li Keqiang proposed establishing the Lancang-Mekong cooperation mechanism at the 17th China-ASEAN Summit in 2014. It was officially declared in November 2015 by the six member states, and the first LMC Leaders’ Meeting was held in south China’s Hainan province in March 2016.

The mechanism identified three pillars of cooperation; political and security issues, economic and sustainable development, and social, cultural and people-to-people exchanges. The five priority areas under the LMC include interconnectivity, industrial capacity, cross-border economy, water resources, agriculture, and poverty reduction.

At the first LMC Leaders’ Meeting, Li noted the LMC was a useful complement to China-ASEAN cooperation, which helps promote the economic and social development of its members, narrow their development gaps, and upgrade overall cooperation between China and ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations). Apart from China, the other five members of the LMC are also members of ASEAN.

Xu Liping, a senior research fellow at the National Institute of International Strategy under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), said the proposal for the LMC mechanism was inspired by some domestic thinktanks, which suggested promoting more interaction among high level officials in the six countries.

“The six countries are showing a ‘spaghetti bowl’ phenomenon due to the complexity of bilateral or multilateral cooperation on various levels, so the birth of the LMC is only natural considering it can better exhibit the geographic closeness and stimulate the economic complementary roles among member countries,” Xu said.

The “spaghetti bowl” effect occurs when the number of trade deals between countries actually slows down trade, instead of boosting it.

Before the LMC, China already had strategic partnerships with the other five countries. China is the biggest trading partner of Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam. It is also the biggest investor in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. According to Chinese government data, in 2015, China’s total trade with the other five member countries reached US$193.9 billion (1.2 trillion yuan).

The LMC is the first multilateral cooperation mechanism in the Mekong River subregion to have been initiated by the six countries. Other economic mechanisms involve players from outside the region, including Japan and the US.

“Apart from economic cooperation, the LMC also focuses on poverty reduction, capacity building and security issues,” Xu said. “In addition, to be more effective, the LMC has a four-level meeting mechanism – working groups, senior officials, foreign ministers and leaders – to smooth out disagreement or potential conflicts.”

So far, under the auspices of the LMC, there have been three leaders’ meetings, three foreign ministers’ meetings, five meetings of senior officials and six working groups.

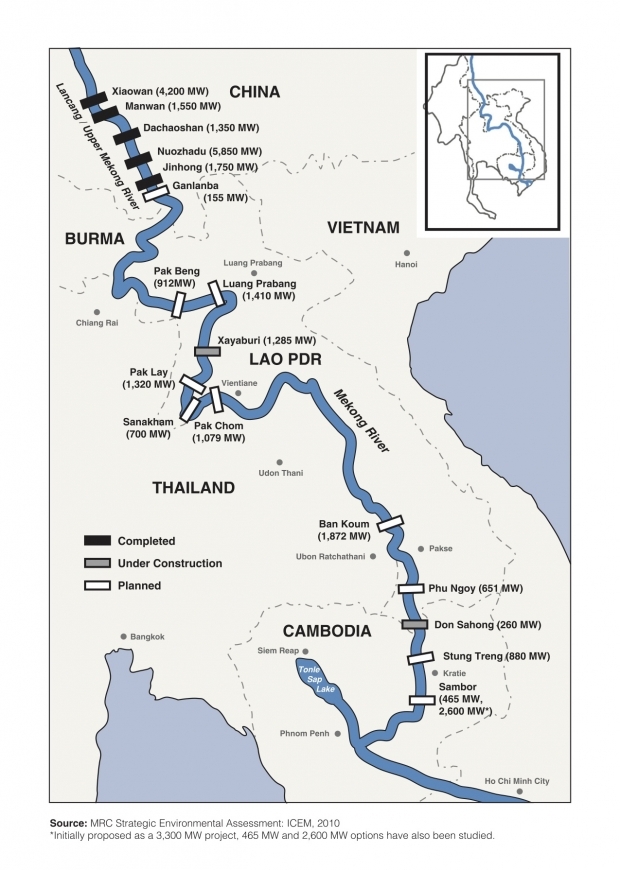

Dams on the mainstream of the Mekong (Source: International Rivers)

In early January, ahead of a visit to Cambodia, Li Keqiang wrote a commentary in The Khmer Times, saying that in the context of a rising backlash against globalization and protectionist sentiments, as well as lack of momentum in East Asian cooperation, the LMC will not only help narrow the development gap within ASEAN and advance ASEAN integration, but also enrich South-South cooperation and efforts to foster more open, inclusive and balanced economic globalization that benefits all.

Achievements and breakthroughs

Under the LMC framework, China has pledged to provide concessional loans of up to 10 billion yuan (US$1.6 billion) and credit loans totalling another 10 billion yuan to promote industrial capacity cooperation and infrastructure construction within the region.

Additionally, China is committed to prioritising the Mekong area for spending in the South-South cooperation aid fund totalling US$200 million (1.2 billion yuan); And to setting up an LMC special fund to provide US$300 million (1.9 billion yuan) in five years to support small- and medium-sized cooperation projects within the region.

The LMC also set up a number of model projects. Forty-five “early achievement” projects were identified at the LMC’s first leaders’ meeting in 2016. By late 2017, these projects had been implemented.

According to Xu, among the 45 projects, some are pre-established and concern local livelihoods; others were pre-existing, such as the China-Lao cross-border railroad or local power plants. Through the LMC mechanism, some infrastructure projects that had been suspended were successfully pushed forward.

“The purpose of such ‘early harvest’ projects was to enhance confidence in multilateral cooperation,” Xu said.

The LMC advocates a “bulldozer” effect, indicating its efficiency in pushing forward unsolved issues or dealing with moribund projects within the region, through a series of communication channels.

Easing tensions with Myanmar

Construction of the Myitsone Dam in northern Myanmar, a joint project involving Chinese investors, which proved controversial in Myanmar, has been on hold for political and social reasons by the Myanmar government since 2011. The fallout from the suspension has damaged both official and non-governmental communications and exchanges between China and Myanmar for some time.

Dialogue and projects have resumed in the last couple of years as diplomatic ties between the two countries improved. Rather than only engaging with regional governments in Myanmar, Chinese companies have recently demonstrated greater willingness to listen to communities and hold dialogues with local NGOs.

In 2017, Global Environment Institute (GEI) was appointed by China’s National Development and Reform Committee (NDRC) to implement a South-South cooperation aid fund, which included distribution of solar panels and clean cooking stoves in Myanmar, through its established community channels. The project has had a positive effect.

“It is apparent that whether community-level projects can be effectively implemented depends on local peoples’ impression and recognition towards China and its companies,” Ji Lin, executive secretary of GEI said.

Xu Liping also confirmed that the LMC offers a new multilateral channel to solve unsettled bilateral issues including, for example, the suspended Myitsone Dam.

An effective multilateral mechanism could allow more stakeholders, such as Thailand and Vietnam, into the investment, which would offer possibilities for the suspended project to resume.

Water management

Among all five priority areas under the LMC, water resource management is the most important. Historically, as China and the Lower Mekong countries strengthened their efforts to develop the waterway, in particular dam construction, the parties are also going through a growing trust crisis due to a lack of negotiation or an overall effective water management mechanism.

If there is flooding, or low flow levels due to upstream drought, the six countries find it difficult to share objective information on water flow and enter into quick negotiations. This sometimes means parties resort to a blame game, making the water issue more complicated.

An effective water cooperation mechanism is vital to achieve fair and rational solutions to water disputes and combat the negative impact of drought and flood in the lower reaches. The LMC has fostered the setting up of a water resource research centre to coordinate among member countries on river flow information sharing and the distribution of water resources.

“In recent years, China has indicated greater willingness to share information on river flows with neighbouring countries and to build cooperation with neighbours with which it shares water resources,” said Maureen Harris, Southeast Asia program director of International Rivers.

“That’s critical because the Mekong urgently needs meaningful cooperation that involves all riparian countries and gives due priority to environmental protection and the human rights of river-basin communities,” she added.

The Mekong urgently needs meaningful cooperation that involves all riparian countries

From late 2015 until early 2016, Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand suffered from severe drought due to the El Niño weather event. In March 2016, as requested by members under the LMC mechanism, China released water to the Mekong River, alleviating the dire situations in Lower Mekong Countries.

Apart from confirming the role of the LMC in water management, Harris also cautioned that LMC governments should think about the projects in a longer-sighted and holistic way, since dams are being approved on an ad hoc, project-by-project basis, without basin-wide assessments and planning.

“It is therefore very important for China to lead by ensuring that the LMC enables effective cooperation over the entire basin and establishes stronger procedures for achieving sustainability,” she said. “China would show leadership and impress the global stage if the LMC prioritised the ecological importance of the river and the participation of the region’s local peoples in key decisions over the river’s future.”

Complementary role

The Mekong River area is a hotspot for various multilateral mechanisms. Apart from the LMC, other competing mechanisms have been set up between the lower Mekong states and the US, Japan, South Korea and India, among others.

Two of the most well-known are the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation Program (GMS) founded in 1992 involving six countries and the Mekong River Commission (MRC) set up in 1995 between Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. The GMS, initiated by the Asia Development Bank, focuses on multilateral cooperation in the economic field. China and Myanmar are not members of the MRC but are involved as dialogue partners.

Despite some observers saying that the LMC is a rival to the longstanding MRC, high-level statements from the LMC argue it is complementary to existing cooperation mechanisms.

According to Professor Lu Guangsheng, director of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies at Yunnan University, the LMC stands out though, since it is expected to get the biggest input and advance most quickly.

Anoulak Kittikhoun, chief strategy and partnership officer of the MRC, admitted to our reporter in a recent email that although the MRC is not a party to the LMC framework, it recognises the LMC initiative as being one that could cement future cooperation among the six basin countries, and it would certainly contribute to reaching the MRC’s goals.

Data sharing

Indeed, the MRC has been cooperating with China on hydrological data-sharing since 2002. New cooperation between the MRC and LMC includes a joint study on the hydrological impacts of the Lancang Hydroelectric Cascade on extreme events and, according to Anoulak, the MRC is working on memoranda of understanding with various LMC centres.

“Thus, the framework would present a new opportunity for the MRC to strengthen ties with China and Myanmar, and we believe we could and are ready to contribute to the new regional cooperation with our 23 years of experience,” Anoulak said.

The Lancang Cascade includes at least six dams, with more planned and under construction.

So far, leaders from the six LMC countries have approved the Five Year Plan of Action of the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (2018- 2022), indicating the mechanism has matured with a clear-cut practical action plan emerging.

“In the next five years, the key is to tie together the efforts of the six members while avoiding interventions from foreign countries outside the region; pushing forward the mechanism while minimising the impact of political uncertainties in certain transitional countries, such as Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand,” said Xu.

This article is republished from The Third Pole