The future of the Mekong River Basin was in the spotlight again at the third summit of the Mekong River Commission (MRC), held on 5 April 2018 in Siem Reap, Cambodia.

The Mekong flows from China (where it is known as the Lancang), through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. However, it is rapidly being changed by large hydropower dams in China and downstream.

The MRC is an important intergovernmental organisation that aims to improve cross border management and sustainable development of the Mekong between Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, with Myanmar and China participating as “dialogue partners”. It works on fisheries, flood control, hydropower, irrigation and navigation.

At this year’s summit, the MRC released findings of a new study it commissioned to provide a detailed analysis of the costs and benefits of hydropower. Carried out between 2012-2017, the study, which is not peer-reviewed, claims that damming the river for power generation will have huge implications for the region.

By 2040, hydropower development could deliver a whopping 16-fold increase in economic benefits. But new dams may reduce income from fisheries by up to 15% and reduce sediment reaching the river mouth by as much as 97% by 2040. Loss of such nutrient rich sediment would be disastrous for fish and agriculture, particularly in the delta.

National leaders and ministers pose for a photo at the third summit of the Mekong River Commission (Image: Mekong River Commission)

As investment rushes into hydropower development in the Mekong River Basin, what can intergovernmental platforms such as the MRC do to promote economic and environmental justice? What role does China play in lower Mekong affairs? To discuss these questions, we sat down with Mr Pham Tuan Phan, chief executive officer of MRC.

Wang Yan (WY): What is your perspective on hydropower construction along the Lancang Mekong River?

Pham Tuan Phan (PTP): At the core of our work (the 1995 Mekong Agreement to cooperatively and sustainably develop the river basin), any proposed construction of hydropower dams on the Mekong mainstream requires prior-consultation, under the MRC Procedure for Notification, Prior Consultation, and Agreement (PNPCA).

The Council study results are very clear that countries’ plans are not optimal and sustainable from a basin-wide perspective. It is understandable as countries plans are made from a national perspective. The MRC will bring countries together to optimise their future plans to increase benefits and reduce potential costs.

I am very interested in the Senegal River Basin (shared between Mali, Mauritania and Senegal) and other examples where countries have jointly owned and operated dams. Such cases tell us that only through joint investment, and sharing costs and benefits, will countries address the bigger impacts of development.

At the same time, the MRC is now working with member countries to develop a joint environmental monitoring scheme for the current mainstream dams. The development of this scheme is based on the recommendations of the past prior consultation processes of three proposed mainstream dams: Xayaburi (2011), Don Sahong (2015) and Pak Beng (2017). [Editor’s note: These three dams are being built in Laos despite MRC recommendations to suspend construction until further impact studies had been completed. A total of 11 dam projects are either under construction or being developed on the mainstream of the Lower Mekong River, with seven on the river in China.]

The scheme will include monitoring five key environment parameters, including hydrology, sediment, water quality, aquatic ecology and fisheries, to be conducted close to the dam sites. Results of the monitoring will inform adaptive management measures of the hydropower projects.

WY: What role does the MRC play in the Lancang-Mekong region as an intergovernmental organisation, particularly in bridging gaps of understanding and shaping common interests?

PTP: I think the MRC has a unique role to play in the regional governance of water and related resources for sustainable development.

It should be noted that there has been high demand for using Mekong water to boost economies in the region. Without a proper dialogue and benefit sharing mechanism, development in one country may mean losses in another. But when there is a proper mechanism for the countries to work together this creates the opportunity for cooperation and peace.

This is where the MRC plays the most important role as the platform for water diplomacy. No other organisation has the mandate or capacity to present an overall integrated basin perspective.

The MRC also has a singular ability to carry out professional analysis both within and across sectors – hydropower, fisheries, navigation, irrigation, water quality, wetlands and so on.

Taking a strategic basin-wide assessment allows us to determine and minimise risks. As a regional body, the MRC can assist here by acting as a facilitator of dialogue and by looking into mechanisms for sharing of benefits across borders.

Such a role was acknowledged and reconfirmed at the third summit by leaders of the MRC member countries. Our dialogue partners (China and Myanmar) also acknowledged the MRC’s importance.

WY: Can you give us some examples of how the MRC is promoting common views among different Mekong countries?

PTP: For example, through our water diplomacy platform the four countries are now increasing bilateral dialogue to build a common understanding of key cross-border water issues, find durable solutions to address issues together, and share best practices in water resources management.

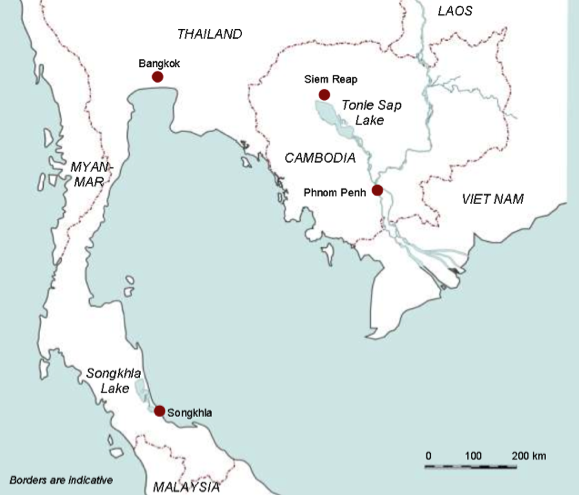

On top of this, the countries also agreed to implement five joint projects that would lead to investment in water development and management. For example, the Mekong and Sekong Rivers Fisheries Management Project between Cambodia and Lao PDR addresses the issue of declining migratory whitefish species, and the Tonle Sap Lake and Songkhla Lake Basins Communication Outreach Project between Cambodia and Thailand supports healthy lake governance through outreach and learning exchange.

Locations of the Tonle Sap Lake and Songkhla Lake (Map: Mekong River Commission)

WY: What are the barriers to such cooperation?

PTP: Our member countries have been cooperating well under the 1995 Mekong Agreement, and with strong support from partners around the world. But since the Mekong River flows through six countries, and only countries in the lower reaches of the river are members of the commission, we have always wanted our dialogue partners – China and Myanmar – to join us.

I believe we could achieve more if the two countries join – for the sake of our shared water and people’s livelihoods. We also need to work closely with the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation mechanism and they should also work with us in the same spirit of cooperation and openness. [Editor’s note: In March 2016 China announced the establishment of a new sub-regional mechanism that promotes cooperation between China and the five lower Mekong countries.]

WY: What is China’s role as a dialogue partner in the MRC? Do you think the MRC is compatible with the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation mechanism, proposed by China?

PTP: Although China is not a full member of the MRC, there is a cooperative working relationship, which has gradually improved in recent years. The basis of that co-operation is good scientific analysis and understanding of the Mekong.

As a dialogue partner with the MRC, China is well aware of the potential consequences of hydropower construction and has indicated its willingness to work together at a technical level on these issues. China has also clearly stated that it will operate the upstream projects so that river flows downstream are maintained at acceptable levels.

At the third summit, China has once again expressed its willingness to work with the MRC and all riparian countries, inviting us to play a constructive role in the Lancang- Mekong water resources cooperation.

But it should be noted that cooperation still needs to be stronger. I am determined to showcase close cooperation and to eliminate doubts that MRC and LMC are competing. I invite China to work closely with us.

WY: Are there any existing mechanisms to provide ecological compensation among MRC members? What’s your view on cross-border ecological compensation?

PTP: We do not have any existing ecological compensation projects yet. At the national level, there are laws and regulations. At the regional/transboundary level, these kinds of schemes have to be negotiated. A possibility would be to have a MRC regional fund for managing and protecting key ecological or environment assets with regional significance.

We are now at an initial stage of preparing a strategy for basin-wide environment management.