Ranish Piyumal Hettige was visibly upbeat when I met with him in Beijing in mid-August. A young official from Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment, he had just completed a one-week training session in the ancient Chinese city of Xi’an, home to the famous terracotta warriors. The training, however, had nothing to do with the preservation of cultural heritage. He was there to learn how his country could respond to climate change, with the help of Chinese experience.

Hettige was among 29 participants from 23 countries who were invited by the Chinese government to take the climate-themed training from August 2 to 15. His fellow trainees hailed from countries as far as Brazil, Pakistan and Lesotho, but shared one thing in common: they were all from the global south.

The training, undertaken by the Chinese Meteorological Administration, was part of China’s climate change south-south cooperation initiative. In September 2015, ahead of the Paris climate summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged 20 billion yuan (US$3.1 billion) for a fund dedicated to climate assistance to developing countries. Two months later, at the summit in Paris, President Xi elaborated that from 2016, China would implement, in the global south, ten low-carbon development demonstration projects, one hundred climate mitigation and adaptation projects, and climate training programmes for one thousand representatives from developing countries. It has since been nicknamed the “10-100-1000 Initiative”.

The training, undertaken by the Chinese Meteorological Administration, was part of China’s climate change south-south cooperation initiative. In September 2015, ahead of the Paris climate summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged 20 billion yuan (US$3.1 billion) for a fund dedicated to climate assistance to developing countries. Two months later, at the summit in Paris, President Xi elaborated that from 2016, China would implement, in the global south, ten low-carbon development demonstration projects, one hundred climate mitigation and adaptation projects, and climate training programmes for one thousand representatives from developing countries. It has since been nicknamed the “10-100-1000 Initiative”.

Hettige is not just one of the thousand trainees. He and many of his fellow participants are also from countries that may host climate mitigation and adaptation projects and the ten low-carbon demonstrations that President Xi announced. His experience highlights aspects of China’s climate change south-south cooperation efforts that have largely stayed outside the global spotlight, and brings attention to a new kind of footprint that China is leaving around the world.

Matching needs and strengths

The training covers a wide range of topics including meteorological services in China and low-carbon economics. It also includes visits to sites where China demonstrates on-the-ground responses to climate change.

“The ‘sponge city’ demonstration was a very good example for all of us,” says Hettige, referring to a tour of a pilot project in Xi’an’s Xixian New District, which is designed to improve absorption, storage, utilisation and recycling of rainwater through improved infrastructure. Sponge cities are just one component of a national effort to prepare Chinese cities for excessive rainfall as a result of climate change.

“In Sri Lanka where most cities are still developing, the infrastructure has to be set up properly,” reflects Hettige. “The rainfall patterns have shifted in Sri Lanka. We should adopt these kinds of water management systems in our developing cities, when we still have a chance to lay the foundation for them.”

A recurring theme in our conversation is the similarities between China and Sri Lanka in their development stages, despite the seemingly wide gap in wealth. “In many places in China, when it rains water gets collected in areas and creates little swamps. The way they are creating sponge cities is very useful for us to learn,” says Hettige.

This is in keeping with comments from developing country respondents to a 2016 United Nations Development Program (UNDP) survey on China’s climate aid. Many believe that China’s own status as a developing country, with its “vast experience in domestic adaptation and mitigation actions as well as access to relevant technologies and a large number of technical experts” is a comparative advantage when it comes to offering assistance to its peers in the global south.

Architects of China’s south-south climate aid programme are keenly aware of the country’s peculiar standing as the world’s largest developing country. “China has its own methods,” Xie Zhenhua, then vice minister of the National Development and Reform Commission, told chinadialogue in 2014 when responding to questions about its contribution to the Green Climate Fund (GCF). This is the financial mechanism under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that enshrines differentiated responsibilities among developed and developing countries on climate change. China has resisted calls for it to put money into the GCF, which it views as representing the historical obligation of developed nations. It sees its south-south cooperation programme, including the 20-billion-yuan South-South Climate Cooperation Fund (SSCCF), as parallel and complementary to such efforts.

As Jin Jiaman, director of the Chinese non-governmental organisation Global Environment Institute (GEI), observed, “the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement creates a global gap of climate financing. China’s climate change south-south cooperation initiatives could make a more timely contribution at this point, though it may not replace developed countries’ role.”

Ambition meets reality

Despite the largely positive response to the south-south cooperation initiative, Hettige admits that he was still unclear how the programme, including the SSCCF and the “10-100-1000 Initiative” functions, even after two weeks of training. “I understand [the SSCCF] is actually trying to help other countries. But in the training, there was no presentation about what it is like, how it is structured, and how it is run.”

Hettige says the lack of understanding among his fellow trainees may be an impediment to them moving things forward back home.

Part of the reason why the initiatives are poorly understood though is because China is still hashing out the details. Chai Qimin, an expert with the National Centre for Climate Change and Strategy and International Cooperation (NCSC), who is involved in the design of the fund explains that “the fund is still in [the] preparatory stage.” He says the main issue concerns the financing of the pledged 20 billion yuan.

“The Ministry of Finance alone would not be able to provide the full amount. Some form of co-financing involving stakeholders such as state-owned enterprises and local governments might be needed, which takes time to formulate,” he says.

China’s climate-related assistance to the developing world did not start with President Xi’s 2015 pledge. From as early as 2007, China’s foreign aid programme already incorporated climate elements. It underwent a major upgrade in 2012 when the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the ministry in charge of climate and energy issues, announced its intent to roughly double its aid for addressing climate change, bringing its annual spending on south-south climate cooperation to about US$72 million.

Since then, a specifically designated Climate Change Equipment Donation Programme has been running under the management of the NDRC’s climate change arm, which coordinates the donation of goods that help recipient countries to better respond to climate change, with a designated line of financing from the Ministry of Finance. The programme has so far operated smoothly with 28 Memorandums of Understanding (MOU) already signed between China and recipient countries. Some of the highlights include China donating a meteorological satellite to Ethiopia so that the African country could “better monitor flood, drought, and changes to its water resources and forestry.”

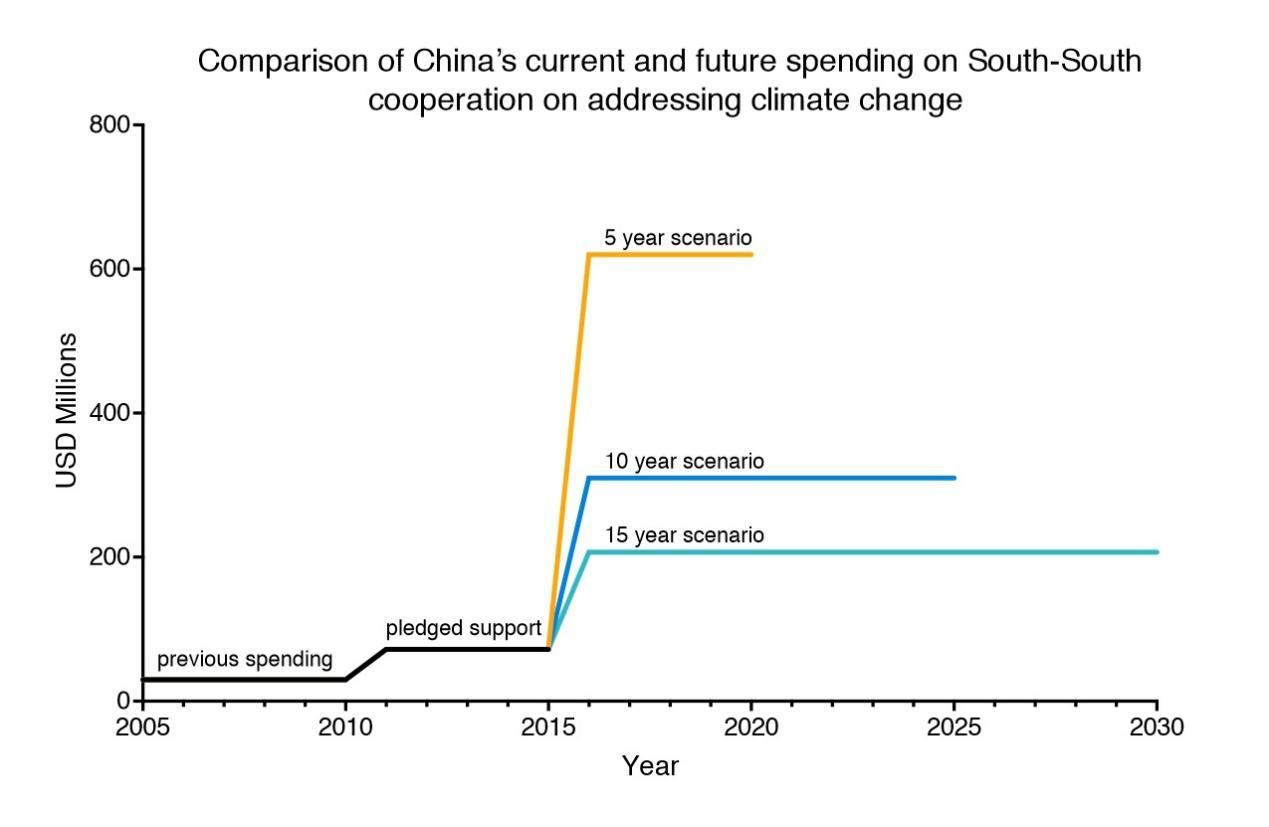

China’s current and projected spending on climate change south-south cooperation based on three scenarios of spreading the 20-billion-yuan fund. Source: UNDP 2016

With the SSCCF still under preparation, much of the “10-100-1000 Initiative” has to be carried out within the financial framework of the original equipment donation programme. This works fine for the 100 adaptation and mitigation projects that are equipment focused. “We have basically adapted the equipment donation programme to fit the 100-project,” Chai tells me.

But for the 10 low-carbon demonstration projects, which are more ambitious, the old foreign aid financing model presents a challenge. “Ministry of Finance has set very strict rules about how such funds can be dispensed,” says Chai, “for example, payments cannot be made directly to the foreign recipients. All procurement is supposed to happen within China.” The above-mentioned UNDP report also confirms that “administrative guidelines dictate that the funds allocated to NDRC for climate change south-south cooperation need to be spent within China.”

The 10 low-carbon pilot projects are expected to go beyond one-off donations and demonstrate low-carbon development within a defined area (e.g. an industrial park or a residential neighbourhood) that involves multiple elements such as planning, design, infrastructure and operation, with participation from local authorities, businesses and civil society. They simultaneously require more substantial funding and more flexible ways to spend such funds. The restricted financing scheme of the equipment donation programme would be ill-equipped to carry such integrated and comprehensive endeavours, which is the main reason why more innovative funding schemes such as the SSCCF might be needed.

Taking shape

The exact form of China’s newly upgraded climate change south-south cooperation initiative is likely to be shaped by multiple stakeholders. Recipient countries have traditionally been influential in determining the content of such aid, as the UNDP survey suggests. “Needs based” and “recipient country driven” are some of the key words describing such projects.

Chinese non-governmental organisations such as GEI, which has been instrumental in facilitating China’s climate change south-south cooperation projects in countries like Myanmar, may also leave their mark in the formulation of the initiative, particularly the low-carbon development demonstration projects. “It’s going to be an innovation and a new challenge for China as it moves from simple equipment donation to integrated development projects, where the government sets standards, civil society participates and green investment from the private sector comes in,” says GEI’s director Jin. “We are feeling our way at the moment. There is no fixed template for such projects yet.” Chai Qimin indicates that criteria for selecting the 10 pilot projects are under development.

The involvement of private sector actors will be a key factor informing the design of China’s south-south cooperation scheme, and not just in getting equipment or service providers on-board. At the 2014 climate talks in Lima, Wang Yi, director of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Policy and Management, implied that commercial funds should be part of the mix that would finance SSCCF. Chai suggests that it is still an “open option” for the SSCCF to accept financing from commercial sources. “Nothing is off the table at the moment, as no final decision has been made yet.”