China’s eight-day holiday, which covers both National Day and the Mid-Autumn Festival, is big business for the tourism industry. As the holiday comes to a close, the China Tourism Academy estimate that as many as 710 million trips will have been made.

Of course, most people will have travelled the conventional way using planes, trains, buses and cars. But despite arriving on the Chinese market just a decade ago, cruises are a growing business.

Almost one million mainland Chinese took a cruise in 2015, according to an industry report from the Cruise Lines International Association. This was almost half of all cruise passengers from Asia, with much of this growth in passengers recent. Between 2012 and 2015, China added 770,000 new cruise travellers, a rise of 66% a year.

The government is doing its part to encourage this. Plans for the tourism sector during the 13th Five Year Plan period call for the development of ports both as embarkation points and as intermediate stops. The plan covers Tianjin, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Xiamen and Qingdao. Half of all cruise ships stopping in China do so in Shanghai.

Islands of pollution

But as the enormous cruise ships carefully inch their way into China’s ports, they bring with them more than tourists and the promise of a good time.

For a start, the air on deck is none too fresh. In July, reporters for Dispatches, a documentary programme for the UK’s Channel 4 television, travelled undercover on a cruise ship carrying almost 2,000 passengers. At some locations on deck, the levels of particulate pollution were as bad as those in Delhi.

Cruise ships don’t need to be fast so tend to have underpowered engines and rely on inexpensive heavy fuel oil that burns to produce large quantities of nitrogen and sulphur oxides. In a ranking of 34 cruise ships plying European waters, the Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU), a German non-governmental organisation, found that only two of the ships had scrubbers and selective catalytic reduction equipment, which convert the nitrogen oxides in exhaust fumes to nitrogen and water.

Axel Friedrich, formerly head of the environmental office at the German transport ministry, said that particulate pollution from an average cruise ship can be equivalent to over one million cars.

And it’s not just cruise ships. The fuel oil used in large ships worldwide contains on average 19,000 parts per million (1.9%) of sulphur, and it can be as much as 35,000 parts per million. For comparison, at the end of this year vehicle fuel sold in China can contain sulphur at no more than 10 parts per million (0.001%).

Dirty port air

It’s not just passengers and crew that are exposed to air pollution from shipping, port residents are harmed by it too. Research has shown that almost 50,000 people in Europe die prematurely each year because of shipping pollution. In China, the figure is approximately 18,000.

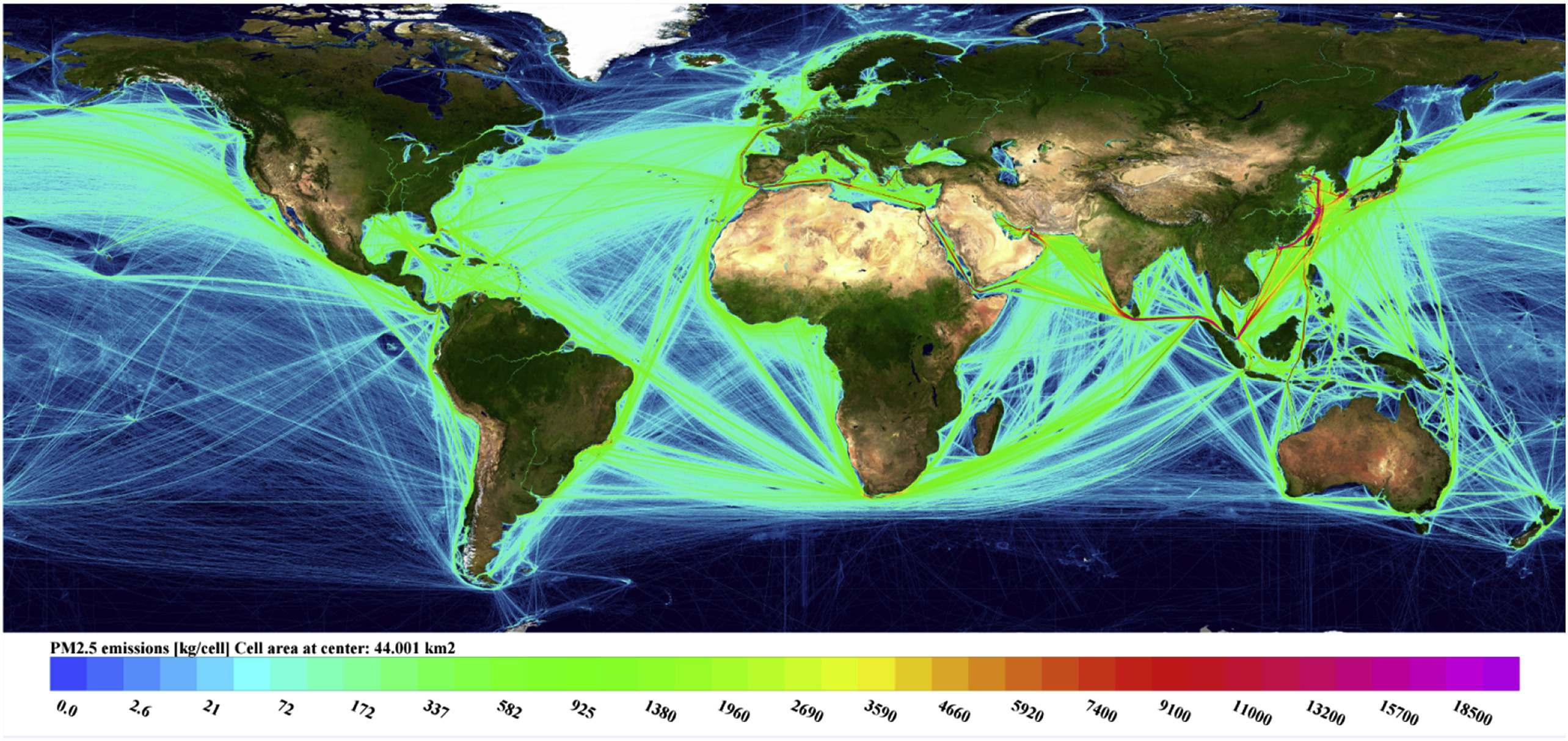

China has seven of the world’s 10 biggest ports, mainly in Shanghai, Guangdong and Zhejiang, and the surrounding areas are densely populated. This makes the threat to local health from shipping pollution hard to ignore. For example, 40% of sulphur dioxide pollution in the port city of Shenzhen comes from shipping. A recent paper on shipping pollution found that the seas off China’s eastern and southern costs have the highest densities of PM2.5 and SOx in the world.

Geographical distribution of the modelled total PM2.5 emissions from shipping in 2015. The legend refers to the emission divided by the area of each numerical grid cell (in units of kg km−2). (Source: Atmospheric Environment)

Geographical distribution of the modelled total PM2.5 emissions from shipping in 2015. The legend refers to the emission divided by the area of each numerical grid cell (in units of kg km−2). (Source: Atmospheric Environment)

Cleaning up shipping

The equipment required to reduce shipping air pollution, such as exhaust scrubbers, selective catalytic reduction and particulate filters, has long been available, according to NABU. Ships can also rely on power provided by ports rather than use their engines when docked.

An alternative fuel, known as distillate oil, is also available that has a sulphur content of less than 0.1%. However, the industry has been slow to adopts these measures because they come at a cost.

Change is happening though. In 2016, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) put forward a new proposal requiring all vessels to use fuel containing less than 0.5% sulphur by 2020. Previously the IMO had decided that vessels stopping within five emissions control areas (the North Sea, the Baltic, the English Channel, North American waters (covering the US and Canada) and the US Caribbean) must use fuel with sulphur content of less than 0.1%. There are no IMO emissions control areas covering Asia’s busy ports.

But in China, time is running out for vessels using heavy fuel oil. A standards document issued in August 2016 on limiting and monitoring pollutants in exhaust fumes from ship engines ruled that by July 2018, all coastal trading vessels must use fuel containing less than 0.5% sulphur, and by July 2021, this will fall to 0.1% sulphur.

According to Zou Shoumin, head of the technical standards department of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the new standard will have huge environmental benefits. The improvement in fuel used by cargo vessels alone, ignoring fishing vessels, will reduce annual sulphur dioxide emissions by 650,000 tonnes from 2021, and particulate pollution by 50,000 tonnes.

China is also controlling pollution from ocean-going vessels visiting Chinese ports. In April 2016, emissions control policies were put in place for key ocean areas: the Bohai Gulf and the Yangtze and Pearl deltas. By 2020, ships entering these areas must use fuel with less than 0.5% sulphur content. This move will bring sulphur dioxide and particulate pollution down 65% and 30% respectively, on 2015 levels.

China is also building power systems on shore so that ships can turn their engines off. In July 2016, the first such system in Asia for cruise ships went into operation at Shanghai’s Wusong International Cruise Ship Terminal.

However, the system is only suitable for a limited number of cruise ships. Ye Xinliang, deputy head at the cruise ship terminal, said there is no single approach for creating a greener cruise ship terminal and an urgent need exists for better environmental management and norms.

To reduce pollution further, Clean Air Asia suggest that China should widen its emission control zones beyond 12 nautical miles, which is much less than the 100-200 nautical miles common elsewhere. It also recommends toughening fuel requirements within the zones to 0.1% sulphur content.

Another issue is the lack of a single monitoring system to ensure vessels actually comply with fuel standards. Jiang Kejuan, a researcher at the National Development and Reform Commission’s Energy Research Institute, told chinadialogue that the Ministry of Transport is looking at how to check whether or not vessels entering the controlled zones have switched to cleaner fuel.

But Jiang said that there is no need for ports to wait for the ministry to act – if the ports want to be greener, all they need to do is refuse mooring to polluting vessels.