The Andes mountain range runs along the western fringe of South America like a giant windbreak. Inland, to the east, gentle plains give way to dense forest and eventually to the vast Amazon rainforest. One tenth of the world’s known species live here, and the respiration of hundreds of millions of trees give it the name ‘the lungs of the world’.

At the foothills of the Andes on the northern edge of the Colombian Amazon lies the small border town of Florencia. The capital of Caquetá province, Florencia is one of the mountainous country’s gateways to the rainforest. In the central square, nearby palm trees stand tall against a backdrop of distant mountains.

On June 8, 2011, four Chinese engineers were kidnapped by armed men 150 kilometres north-west of here, in a place called San Vincente del Caguán, and held captive deep in the mountains. They were employed by a company subcontracted to Emerald Energy, a subsidiary of China’s Sinochem Group. The kidnappers were members of FARC, Colombia’s radical leftist guerrillas. Since commencing armed struggle against the Colombian government in 1964, FARC has used kidnapping and the drug trade to control territory outside the reach of the Colombian government in an attempt to achieve political aims it says represent the grassroots population. Statistics show that 220,000 Colombians died and around 7.3 million were displaced during the 52 year conflict – a heavy toll for a country with a population of only 48 million.

In the then FARC stronghold of Caquetá, Chinese oil workers found themselves tied up in a civil conflict in a foreign land. In November 2012, after 17 months in captivity, the four workers were freed – not because of a ransom payment or daring rescue, but because of a fundamental political change: In October 2012, FARC and the government started historic peace talks and the release of the remaining foreign hostages was a symbol of good faith.

Four years later the country witnessed another historic change.

Ready for business

On November 30, 2016, the two sides reached an overall peace agreement after the rejection in a referendum the previous month and the renegotiation of a new deal with significant amendments. After half a century of fighting, FARC and the government ceased fire and Colombia entered a post-conflict, or at least a post-peace deal (post-acuerdo), era. FARC laid down its weapons and became a legitimate political party. On December 10, Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos gave a moving speech in Oslo, Norway, as he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize.

There is much rebuilding to be done in Colombia. Reintegrating FARC soldiers into peaceful society will be a difficult process and there is still much bad blood. But the process has started. As Santos said in his speech: “The long-awaited process of implementation has begun, with the invaluable support of the United Nations. This agreement marks the beginning of the dismantling of an army – this time, an irregular army – and its conversion into a legal political movement. With this new agreement, the oldest and last armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere has ended.”

Peace means opportunities for Colombia’s political and business elite. When the peace talks started in 2012, Santos embarked on a China “roadshow”, inviting Chinese firms to invest in Colombia as part of China’s “going out” strategy. On the eve of the referendum on the peace deal, Colombia’s ambassador to China, Oscar Rueda Garcia, said in an interview with the Xinhua news agency that the positive changes brought by the peace process would mean more investment and partnership opportunities for Chinese firms, including reconstruction in conflict and rural areas.

Peace means opportunities for Colombia’s political and business elite. When the peace talks started in 2012, Santos embarked on a China “roadshow”, inviting Chinese firms to invest in Colombia as part of China’s “going out” strategy. On the eve of the referendum on the peace deal, Colombia’s ambassador to China, Oscar Rueda Garcia, said in an interview with the Xinhua news agency that the positive changes brought by the peace process would mean more investment and partnership opportunities for Chinese firms, including reconstruction in conflict and rural areas.

Chinese firms were cautiously optimistic about the improvements in Colombia’s investment environment. According to analysis by the China International Chamber of Commerce for the Private Sector, mining, travel and agriculture would be open for investment, but companies should be wary of violent crime filling a vacuum left by FARC.

Dissent in the mountains

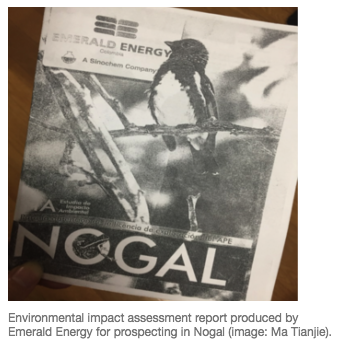

After the trauma of the kidnap, Sinochem finally had the peace and opportunity it had been waiting for. The company has witnessed political, economic and environmental changes in Colombia – it has worked in the country since 2009, when it purchased UK firm Emerald Energy, which owned assets mainly in Colombia and Syria. The acquisition gave Sinochem a number of oilfields in Colombia, making the country a reliable supplier of oil to the group. Colombia is South America’s third largest producer of oil, after Venezuela and Brazil. In 2013, with the security situation improving, Emerald Energy announced the exploration of three new oilfields in partnership with the national oil company. Of these, the Nogal block in Caquetá was regarded as enjoying “low prospecting risk, high resource potential.”

But the development at Nogal hasn’t received a wholehearted welcome in Florencia, or Caquetá more broadly. The 240,000-hectare block isn’t far to the south of the city and encroaches on the Amazonian regions of Morelia, Milan and Valparaíso. Before drilling can officially start, Emerald Energy needs to carry out stratification and seismic testing across about 20,000 hectares.

There is much debate about the project in the village of Valparaíso. It takes three hours on a rural bus and then a motorbike over bumpy roads to get here. Wide and beautiful mountain plains are studded with patches of pristine forest, with livestock and horses grazing leisurely. Farming couple Blanca Barragán and Simeón Cortés have built a simple wooden home here. Ripe oranges hang from the trees out front, while a sapphire blue parrot rests in the branches. In the kitchen Blanca is preparing dinner and recounting the time she was electrocuted by a river stingray whilst fishing in the forest.

The last of the evening sun filters in through cracks in the walls, illuminating the faces of several gathered farmers.

“We’re farmers, the oil industry won’t mean anything for us,” says the youthful Rigoberto Valencia, the most talkative of the group. He worries the seismic testing will affect the local water supply. Farmer Jose Antonio Saldarriaga tells me that he raises over 100 head of cattle and plants corn, bananas and cassava on his farm. There’s also a patch of pristine forest, watered by a small stream and a spring. “The farm is our only livelihood.” Wastewater and possible leaks from oil drilling are a concern for the farmers.

Emerald Energy has not ignored these worries. Back in 2014 the company arranged a number of meetings in Caquetá to tell community representatives about the project. The environmental impact assessment for prospecting in Nogal was completed late last year. The assessment evaluated the impact of work on the local water, forests, biodiversity, the community and economy. The assessment said there would only be “moderate negative impacts” on water quality.

But the meetings weren’t enough to convince the locals. “It was more like a one-sided lecture,” complains Saldarriaga. The villagers are also critical of some of the report’s conclusions, particularly those regarding one of the area’s endangered animals, a monkey called the Caquetá titi (Callicebus caquetensis). The report said that: “Although there is data showing the monkey lives in this region, no sightings were made during the evaluation period.” The villagers think that might have been deliberately downplayed. “We hear them in the trees on our farms!” says Luis Eduardo Ortiz, pushing open the door and pointing off into the forest. Javier Garcia, a biologist at the Universidad de la Amazonia and the discoverer of this species of monkey, says it does live here – and that its distinctive call is easy to identify.

But the meetings weren’t enough to convince the locals. “It was more like a one-sided lecture,” complains Saldarriaga. The villagers are also critical of some of the report’s conclusions, particularly those regarding one of the area’s endangered animals, a monkey called the Caquetá titi (Callicebus caquetensis). The report said that: “Although there is data showing the monkey lives in this region, no sightings were made during the evaluation period.” The villagers think that might have been deliberately downplayed. “We hear them in the trees on our farms!” says Luis Eduardo Ortiz, pushing open the door and pointing off into the forest. Javier Garcia, a biologist at the Universidad de la Amazonia and the discoverer of this species of monkey, says it does live here – and that its distinctive call is easy to identify.

Increasing opposition

The villagers have long lived under the shadow of armed conflict, and it isn’t just environmental concerns that make them wary of the oil industry. Prior to 2006 FARC occupied the forests deep in the mountains of Caquetá, and private militias (called paramilitary groups in Colombia) sprung up to combat the guerrillas. The constant fighting forced many villagers to leave.

The villagers are worried that the arrival of the oil companies will end a long-awaited peace and that the influx of money will cause disaster. “The militias signed a deal with the government ten years ago and disarmed – but not completely. The temptation of all the oil money may tempt some of them back into organised crime,” said Yolima Salazar, head of the community affairs office of the Catholic Church in Morelia.

In June 2015, worried villagers of Valparaíso decided to step up their efforts, blockading the only road to one of the seismic testing points to prevent the company from carrying out its work. The riot police were sent in and used tear gas to disperse the villagers. One villager, Juan Pablo Chávez, was left bleeding badly after being struck by a tear gas grenade. Many others were hurt. Violence had returned to the mountain village, albeit for different reasons.

Wilson Vaquiro (l) and Luis Eduardo Ortiz display the sign they held when protesting the prospecting activity. The picture is of a Caquetá titi monkey (Image: Ma Tianjie).

Meditating on the Amazon

Jorge Reinel Pulecio is head of the “Peace Coordination Office” at the Universidad de la Amazonia. His office aims to bring each party to the peace agreement into education and research to help find a way forward for this conflict-ravaged place. On the controversy over Nogal, he said: “The peace agreement was a watershed. One thing the villagers think they should have is a greater right to be heard [as] promised in the peace agreement; the other is that the government and big businesses see a chance to reduce costs.” Before the ceasefire security costs and even ransoms were part of doing business in FARC-held areas – money that companies no longer need to spend.

Sinochem and the local community may have differing opinions on how fierce the opposition to the Nogal project is. As a signatory to corporate sustainability initiative the UN Global Compact, Sinochem lists public welfare undertakings in the region in its annual corporate social responsibility reports, including supporting training in local traditional woodworking skills and building roads. Emerald Energy has also held the usual meetings about the project. In September this year it employed a third party body, the Institute for Conversation, to talk with local representatives, NGOs and academics. According to Caquetá regional government official Carlos Ramirez, who attended those talks, the company has recognised the problem it faces with negative public opinion.

Although locals complain about some of the things Emerald Energy has done during prospecting, such as starting work without landowners’ permission, these are hard to confirm.

But what is certain is that there are different views on how the edges of the Amazon region should be developed. As Jesus Alfredo Gomez of Morelia said, they have a “fundamental” opposition to oil companies working here.

As Gomez speaks, Hernando Cuellar walks into the yard behind us and gift me a plump golden fruit. “It’s called arazá, unique to the Amazon.” I eat it skin and all – the flesh is soft and sweet, and tastes a bit like a mango. “The quality of the fruit here is fantastic, but we can’t transport them, so they rot on the ground,” he says, pointing at the fruit lying in the yard.

As Gomez speaks, Hernando Cuellar walks into the yard behind us and gift me a plump golden fruit. “It’s called arazá, unique to the Amazon.” I eat it skin and all – the flesh is soft and sweet, and tastes a bit like a mango. “The quality of the fruit here is fantastic, but we can’t transport them, so they rot on the ground,” he says, pointing at the fruit lying in the yard.

The farming families in the area go back generations and have their own ideas about how the region should develop – ideas which are shared by others. Catequá’s financial comptroller Eduardo Moya thinks the “uniqueness” of the Amazon region means the government should treat it differently. That uniqueness comes from “a more vulnerable environment” and “high value added products” – value that stems from preserving the environment and sustainable methods of production. “Coffee, coca, fruit, even freshwater fish – all of these have potential on international markets,” he says.

Back in the wooden hut in Valparaíso I ask Rigoberto what other development opportunities there are for Caqueta, if not oil. “We need the chance to bring our products to market, we need good roads and agricultural technology.” He points at the dirt road running past the firm. “How are we meant to compete with anyone else?”

In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, President Santos said: “It is quite comforting to be able to say that the end of the conflict in Colombia, the most biodiverse country per square kilometre in the world, will yield high environmental dividends.”

But in Florencia many are dubious about the national government’s concern for the environment. Support for oil drilling in the Amazon has cast a shadow over showy international environmental commitments – as part of the Paris Agreement Colombia has promised Net Zero Deforestation by 2020. In 2014, Colombia also signed up to the Bonn Challenge to restore one million hectares of forest by 2020, an action that would sequester an estimated 90 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

The opposition in Florencia reflects a fundamental challenge facing China’s energy investment strategy in Colombia, and even Latin America as a whole. Kevin Gallagher, an expert in China-Latin America trade at Boston University, has calculated that 87% of investments by Chinese policy banks in Latin America have been in energy, mining and infrastructure – with significant investments in fossil fuels. In comparison, these sectors account for only 34% of World Bank investments.

In the slightly cramped room of the Peace Coordination Office at the Universidad de la Amazonia, Professor Pulecio is anxious: “We all know China is currently investing huge amounts in a transition to renewable energy at home, and you’ve made incredible innovations in renewable technology. If China comes to Latin America, to Colombia, to the Amazon, only to extract oil and natural resources, rather than assist a similar transition, that would be a huge failure.”

There is no sign the tug-of-war over Nogal will end soon, and in places like Morelia and Valparaíso, it has reached the courts. A representative of Emerald Energy, Juanita Latorre, declined our emailed request for an interview.

We have no way of knowing if the winds of discontent blowing out of the mountains of Caquetá will be felt in the boardrooms of Bogotá and Beijing.

Editor’s note: This article was produced as part of Diálogo Chino’s unique paired journalism fellowship that brought together a Chinese and Colombian journalist’s perspectives in reporting on the social and environmental impacts of Chinese investments in Colombia in the post-peace deal era. The Colombian journalist’s report can be found here.