China has long been the object of scrutiny at COP – the annual United Nations climate conference – as the world’s largest emitter. Once seen as an obstructionist, the country has become the darling of a climate community desperate for a champion after Trump’s election. But this elevated status has also invited further inquiries into its climate actions.

At this year’s COP in Bonn, Germany, civil society observers began to interrogate China’s vast global development ambitions. Of the 195 nations that attended the climate negotiations, 68 of them are members of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – China’s dominant foreign policy. The initiative started as an effort to build infrastructure along the historical Silk Road routes and has since ballooned into a catch-all for the country’s booming overseas development.

This conjoined development-diplomacy has strong implications for climate change. China is increasing emissions in Belt and Road countries by offering coal-fired power plants as a solution to their energy poverty crises. At the same time, China is providing climate finance and building renewable energy projects in some of the same countries.

Weighing these actions against each other, does China’s overseas footprint align with the Paris Agreement? As a convener for civil society debate on the Belt and Road Initiative, the Bonn COP helped to inform a verdict.

Climate finance with Chinese characteristics

One of the central negotiating issues at the COP was how to provide financing to developing countries to mitigate and adapt to climate impacts. Some, like this year’s co-host Fiji, need immediate help to respond to rising sea levels. In 2009 at the Copenhagen climate talks, developed countries pledged to mobilise US$100 billion (661.4 billion yuan) per year in climate finance by 2020, a pledge further cemented in the Paris Agreement text.

But the Trump administration has dealt a blow to this commitment by refusing to make further payments to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the UNFCCC mechanism for national governments to deliver climate finance. With the US abdicating, China has come under pressure to step up.

"Others expect us to fill the financial gap, but we do not plan to do so," said Xie Zhenhua, China's top climate envoy. "We are not obliged to pour money into the Green Climate Fund. We insist on our stance as a member of the developing countries."

Although per capita income in China has risen significantly in recent decades, it is still well below the developed country line as defined by the World Bank.

China may have no intention of filling the void in the GCF left by the US, but it has offered to assist developing countries on its own terms. At the Paris climate talks in 2015, it pledged US$3.1 billion (20.5 billion yuan) of climate financing to developing countries through its South-South Climate Cooperation Fund.

The GCF and China’s own fund will likely support many of the same recipient nations, begging the question: why does China not contribute directly to the established fund? Joining the body of developed country donors to the GCF might send the signal that China is ready to abandon its “common but differentiated responsibilities” position and be answerable to all the expectations of a developed country on climate change.

China’s home-grown climate finance scheme allows it to maintain its identity as a developing country while adopting the magnanimity of a developed country.

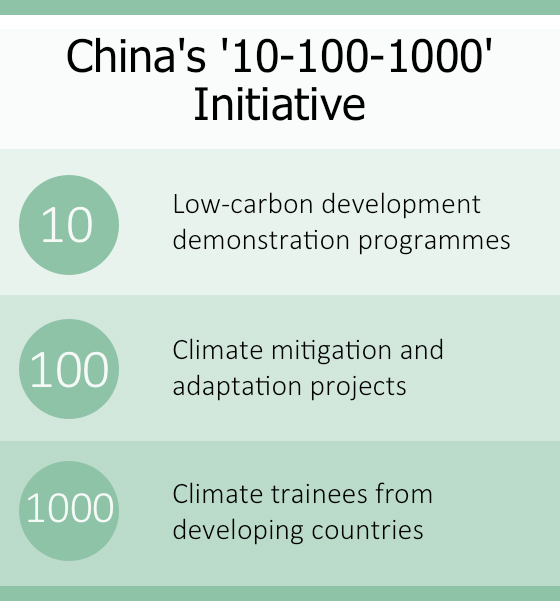

China’s fund is expected to support the “10-100-1000” South-South climate cooperation initiative, developing ten low-carbon development demonstration projects, one hundred climate mitigation and adaptation projects, and climate training programmes for one thousand representatives from developing nations.

The details of the fund are still being hashed out according to Chai Qimin of the National Centre for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation (NCSC). But some of the training programmes are already underway. Arnord Simwaba, one of Zambia’s COP delegates as director of the Department of Energy, told me he had travelled to Hangzhou for a three-week training course on mini-hydro development.

“In terms of training our people, so many people from the energy sector – be it from the government side or from the utility, that is the power generation company – so many officers … they go to China for short courses,” said Simwaba.

Beyond the border of the Paris Agreement

Beyond the border of the Paris Agreement

China may be charting its own path on climate finance but its efforts align clearly with the aims of the Paris Agreement. This cannot be said for its Belt and Road Initiative. The BRI has no direct oversight under the agreement, which is built on country commitments known as Nationally Determined Contributions to deliver emissions cuts within national borders. It has no provisions for monitoring overseas investments.

This is a blindspot for the Paris Agreement. BRI countries (including China) contribute over half of global greenhouse gas emissions and their emissions are projected to grow. Shaped by the Belt and Road, their growth trajectories will determine whether the world can limit average global temperature increase to two degrees Celsius.

Guo Hongyu of Greenovation Hub, a Beijing-based non-governmental organisation, highlighted that the Nationally Determined Contributions of many BRI countries are conditional, meaning they will only be able to achieve low-carbon development with sufficient financial support from other countries.

Whether BRI investments will align with a low-carbon path in these countries rests in large part on China applying stricter standards to its overseas financing to promote low-carbon projects.

Nguyen Tuan Anh, Vietnam’s Minister of Planning and Investment, reported that China is still investing in high-carbon infrastructure. “The Chinese investors presently in Vietnam appear interested mainly in coal power generation,” he said, while also noting that Chinese investors have begun building solar PV manufacturing facilities in the country. He cautioned that the Vietnamese power sector still requires major investment and will need to carefully balance its infrastructure needs and climate goals.

Recent research shows that Vietnam’s experience is not unique. Chinese overseas investment skews heavily toward coal power over renewable energy, particularly in Southeast Asia. This trend could be on the decline, though; a study from the Global Environment Institute shows that Chinese investment in coal-fired power projects has decreased slightly since it peaked in 2010.

Aligning overseas finance with Paris

How to manage and redirect China’s overseas finance was a major topic of discussion at the COP Belt and Road side events. Ma Jun, chair of China’s Green Finance Committee, spoke about the committee’s new Environmental Risk Management Initiative for China’s Overseas Investment. Its guidelines call for Chinese investors operating overseas to adhere to the highest environmental standards for their industry whenever possible.

Ye Yanfei, an inspector at the China Banking Regulatory Commission, said that the government oversight body released its own guidelines on environmental and social risk for banks investing outside of China in January. To ensure they are meeting the guidelines, the CBRC dispatches teams to inspect the bank’s overseas investments, according to Ye.

Guidelines are certainly helpful for setting standards and shifting expectations but they remain non-binding, said Zhang Jingjing, an environmental lawyer, who has visited Chinese projects across the world. She told chinadialogue that “it’s mainly the laws of the host nation that control the environmental and social risks of projects with Chinese investors.”

She added that the National Development and Reform Commission is working to strengthen the domestic legal framework. It has drafted a Method for Management of Company Investments and is creating a list of sensitive sectors that will require extra approval processes for overseas projects.

Multilateral institutions that provide project finance such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, New Development Bank, and Asian Development Bank are also helping to raise standards. Increasingly, these banks are focusing their infrastructure investments on green rather than conventional energy projects.

Speaking in Bonn on the Asian Development Bank’s new strategy to double climate finance by 2020, Lu Xuedu, the bank’s lead climate change specialist, said it has signed an agreement with China’s Ministry of Finance to support BRI projects. “We will continue to use ADB’s high standard on environmental safeguarding and climate change … so that we can really have a demonstration role for the Road and Belt development,” he stated.

Growing expectations

How countries choose to meet their commitments to reduce emissions under the Paris Agreement is their responsibility, meaning China is not technically accountable for the carbon emissions of projects it invests in abroad.

However, during a US-China bilateral meeting in 2015, China agreed to “strictly controlling public investment flowing into projects with high pollution and carbon emissions both domestically and internationally.”

And in the wake of President Xi’s speech at the 19th Party Congress in October where he described China as a “participant, contributor, and torchbearer in the global endeavour for ecological civilization,” the nation will face increasing pressure to align its BRI decision-making with its rhetoric.

China’s efforts to support other countries through South-South cooperation show the country stepping beyond its status as a developing country in the realm of climate diplomacy. But these initiatives do not cancel out the country’s overseas fossil fuel projects. The greater test of China’s global climate leadership remains whether it will commit to shifting Belt and Road investments from high- to low-carbon infrastructure.