Mozambique’s forests are as magnificent as they are threatened. As with so many forests around the world, weak laws, corruption, and illegal and excessive logging are destroying this precious resource.

But together with its largest trading partner China, Mozambique has a chance to turn things around, as we show in China in Mozambique’s forests: a review of issues and progress for livelihoods and sustainability – a new report from the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) published today.

Regulation that encourages Chinese companies and their Mozambican partners to invest in high value processing within Mozambique and better law enforcement is crucial to stop the destruction.

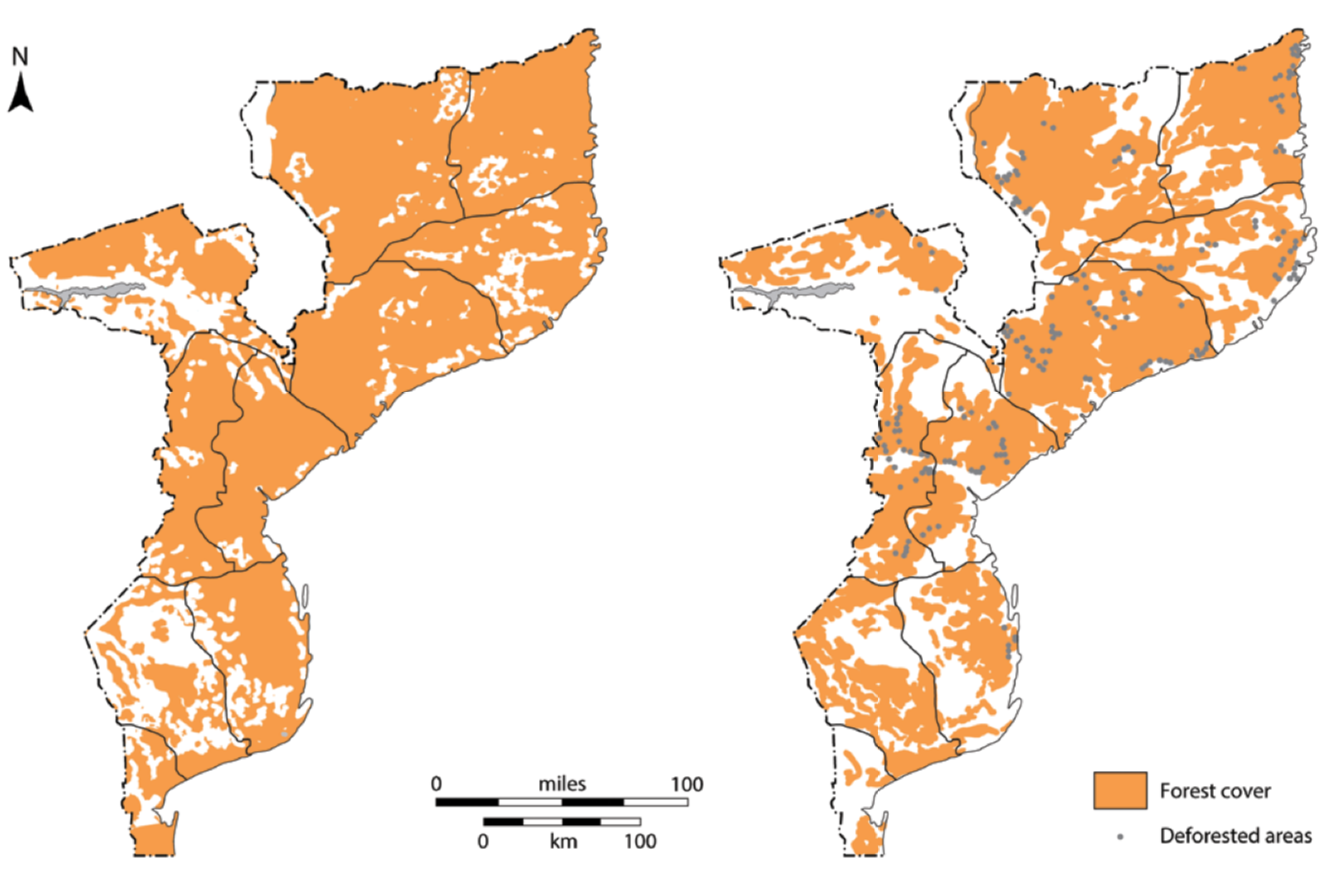

Alarmingly, 219,000 hectares of Mozambique’s forests are cut down every year – about 10,000 square metres every minute.

This has urgent implications for biodiversity and for mitigating the impacts of climate change. It is also significant for the state of Mozambique’s economy and its ability to develop in a way that is sustainable and can benefit its people.

Change in Mozambique’s forest cover between 2003 and 2013

Source: Simplified and redrawn by IIED from higher resolution maps by DINAF

A stronger partnership

Mozambique exports 93% of its timber to China, so the country has a pivotal role in ensuring that Mozambique’s forests have a future. In June, the two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in which they agreed to work together to stop forest destruction and enable Mozambicans to share the benefits from forest production with Chinese investors.

This move is a crucial opportunity to help save these forests. Through it, Mozambique can become an influential example to other countries in how to develop practical systems for processing forest products based on sustainable sourcing.

China’s commitment to invest in establishing timber processing plants in Mozambique means it can help end the export of whole logs to China, introduce modern processing facilities that are less wasteful and so use fewer trees, create jobs for local people, and increase much needed tax revenue.

Mozambique exports 93% of its timber to China

Pioneering Chinese companies in Mozambique are already starting to do this. One such company is Mr Forest Ltd. I met its CEO, Zheng Fei, in 2017. He came to Mozambique 15 years ago and, in his words, “fell in love with the local trees”.

Zheng is a prime example of how it is possible to love the forest while also using it for business. He has developed sustainable operating practices, adopted Chinese government guidelines on good forestry, and supports associated community engagement to market non-timber forest products. But more is needed from other Chinese investors.

Businessman Zheng Fei, CEO of the company Mr Forest Ltd, came to Mozambique 15 years ago. In his words he 'fell in love with the local trees' (Image: Tamarind Tree/IIED)

Ending illegal logging

The agreement also expects the two governments to work together to develop a bilateral verification system to combat illegal logging and sustainably manage forests. As our report shows, it is vital this includes developing a bar-coded, internet-based, electronic timber tracking system that allows real-time data entry and checking throughout the supply chain. This is crucial to protect forests and tackle corruption.

The volume of timber leaving Mozambique has often been much higher than officially recorded. According to UN Comtrade, in 2013 Mozambique reported exporting 280,796 cubic metres of timber to China. The amount recorded on arrival was more than double this at 601,919 cubic metres.

Inspection and monitoring also need improving. Mozambican forest experts have calculated that the number of forest inspectors needs to increase from 630 to 1,800 to help implement any new timber tracking system.

Long-term management

Key reforms to Mozambique’s forest management and forest law are also required. One problem is how forest land is allocated for logging. The use of simple licences is particularly destructive.

These licences are granted for up to 10,000 hectares of forest designated for logging and are renewable every five years. But some are significantly larger at 60,000 hectares. The short licence period makes these forests especially vulnerable to wholesale plundering of valuable species as there is no incentive for companies to give smaller trees time to mature for future harvests.

Scrapping simple licences and ensuring all concessions are for 50 years, with regular assessments of compliance with sustainable management plans, needs to be standard.

In addition to making sure the MOU is effective in establishing processing facilities for industrial-scale concessions within Mozambique, the country’s forest law also needs to grant commercial forest rights to local forest communities, which already have land rights. This could include establishing new community forest concessions that are conditional on keeping the forest intact. This would give them the right to make money from timber sales to third parties, increasing their incentive to protect the forests.

The action needed to save Mozambique’s forests for future generations is clear – it is vital that Mozambique and China work together to make this a reality.

![Embankment construction on the Sundari river near Raghunathpur [image by: Peter Gill]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2018/08/IMG_9106-300x225.jpg)

![A resident of Raghunathpur standing on an embankment with bamboo revetment on the Sundari river [image by: Peter Gill]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2018/08/IMG_9311-300x225.jpg)