Gold is the most valuable metal in a phone. One tonne of gold ore contains around 1-5 grams of pure gold – but a tonne of mobile phones contains upwards of 300 grams, explains Professor Jason Love. In fact, an estimated 7% of gold in circulation around the world is contained in the circuitry of electronic devices, he points out.

Love is head of inorganic chemistry at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. His focus is on using chemistry to recover valuable and toxic metals from old technology. The digital junk people throw away offers a huge and valuable resource if the metals can be recovered and recycled through what’s known as “urban mining”. This can also avoid the extraction of new materials.

The professor’s team is developing a new compound that can be used to separate gold from other elements in a mobile phone.

“All electronics contain lots of valuable metals, and we really should be recycling them because it takes a lot of effort and energy to get them out of the ground and separate them from other materials,” says Love.

The team is aiming to make a process that is more environmentally friendly than smelting, which is the most common way of recycling phones, but which is very energy intensive, he adds.

The next stage of the research is to team up with a geoscientist who is interested in developing a biological method using bacteria to dissolve metals, which could be combined with the chemical method.

As the world becomes increasingly high-tech, a huge environmental problem is piling up. Our old phones, laptops and TVs often end up in landfills or in unregulated reprocessing, polluting air, soil and water as toxic materials seep out. Meanwhile, mining virgin materials to replace discarded products generates more pollution and carbon dioxide emissions.

But the value of e-waste as a resource is growing. Modern electronics contain a variety of precious metals including gold, copper, platinum, and rare earth elements, such as neodymium and tantalum.

The Global E-Waste Monitor (GEM), a project involving the United Nations University, International Telecommunications Union and the International Solid Waste Association, estimated the total value of all raw materials present in e-waste in 2016 at approximately 55 billion euros.

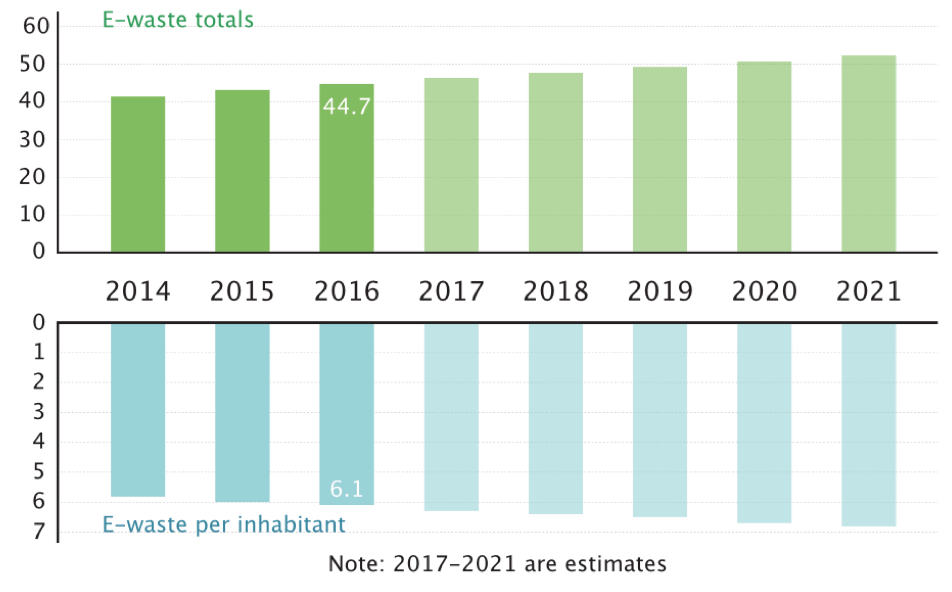

The GEM also estimated that nearly 45 million tonnes (Mt) of e-waste was generated globally in 2016, which is expected to grow to 52.2Mt by 2021.

Estimate of global e-waste (million tonnes)

Source: Global E-Waste Monitor

The problem is that the vast majority of e-waste is not recycled. Two-thirds of the world’s population is covered by laws governing e-waste, but only 20% is recycled properly, according to GEM. Around 4% is thrown in the bin, while 76% is unknown, or recycled under poor conditions for environmental and human health. Companies lack the incentive to collect and process e-waste as the cost of sourcing raw materials is often cheaper.

Challenges

China’s e-waste waste is expected to grow from 15Mt in 2020 to 28.4Mt by 2030 – making it a larger generator of e-waste than the United States or the European Union.

However, it has also emerged as a leader in urban mining, says Xianlai Zeng, associate professor at the School of Environment at Tsinghua University, who specialises in urban mining and e-waste management.

Collecting e-waste is the main obstacle for both developed and developing countries, adds Zeng.

In Europe, e-waste is regulated by the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive, which contains measures to improve collection, treatment and recycling of electronics at the end of their life.

There, collecting e-waste from consumers is still a major challenge. “A lot of small electronics end up in the bin. There’s nothing to compel the consumer to take them to a civic amenity site,” says Susanne Baker, head of environment and compliance at trade body Tech UK.

The Chinese government has promoted collection and extraction of valuable materials from e-waste through subsidies. For example, metal recovered from one cathode ray tube (CRT) television earns US$13, which Zeng says has been vital to the attractiveness of urban mining in China.

The subsidy has meant that urban mining is cheaper than virgin mining in China. A study by Zeng, together with professor Jinhui Li from Tsinghua University and professor John Mathews from Macquarie University in Australia, estimated that virgin mining for the metals in a CRT TV was around 13 times more expensive than extracting the metals through urban mining. For PCBs, the materials were seven times more expensive through virgin mining, it found.

How is it done?

Of the e-waste that is currently recycled, most is carried out by industrial smelters. Printed circuit boards from laptops are crushed and transported to these facilities, which can then remove copper, gold and silver. Smelters are energy intensive, heating up to 2000 degrees Celsius, which produces a large amount of carbon dioxide.

The difficulty with removing metals from e-waste is that the materials used in electronics are very complex, for example, different metals, glasses, plastics, and solder connectors. They need to be physically disassembled before anything can be done with them, adds Prof Love.

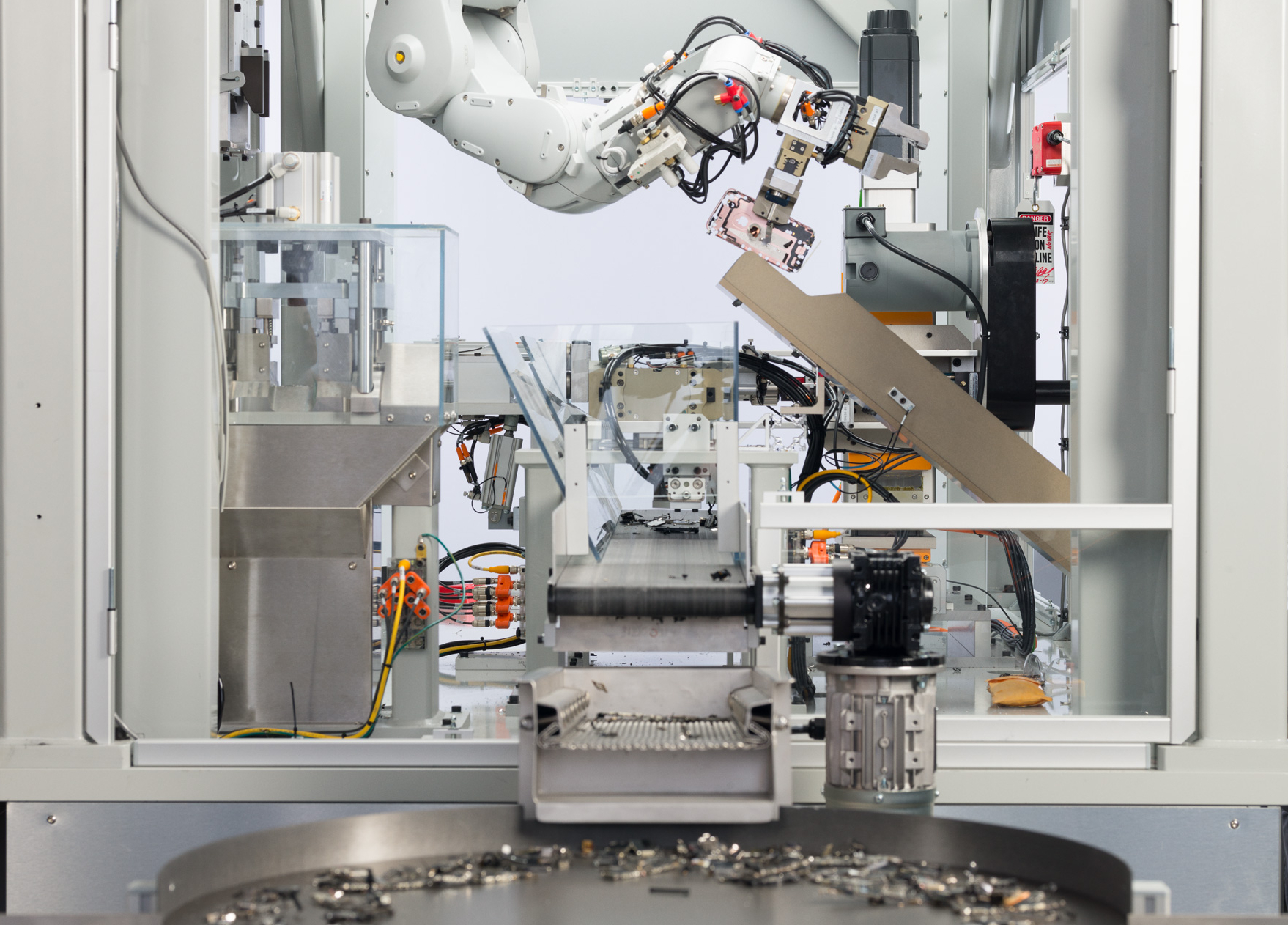

Daisy the robot can disassemble 200 iPhones every hour and doesn't require rest breaks (Image: Apple)

Manufacturers see the potential

Some global electronics manufacturers have begun to look into incorporating urban mining into their supply chains. Technology giant DELL is using gold recovered from computer motherboards in new ones, and has also partnered with a jewellery designer to create earrings and cufflinks from the metal.

Gold from this reclaimed process has an environmental impact 99% lower than conventionally mined gold, according to a report last year by analysts Trucost. The company has pledged to recycle 100 million pounds of recycled content into its product portfolio by 2020.

Meanwhile, Apple has developed a robot to disassemble its iPhone. The latest incarnation, Daisy, can take 200 iPhones apart every hour, and removes and sorts the components for recycling. The tech firm has a goal to completely eliminate virgin materials from its product manufacturing.

The value chain

Efforts have also been made to make data on metals and rare earth elements more accessible. An urban mine database has been developed by a collaboration involving research institutes, geological surveys and industry.

The so-called ProSUM project identifies the largest stocks of specific materials, and allows users to see the changing makeup of e-waste over time across the EU. For example, it reveals those metals that are increasing in use and those that are decreasing. It aims to provide a factual basis for policy makers to design legislation, and for academia to define research priorities and innovation opportunities in recovering raw materials.

Meanwhile, University College Cork is working on a project to make urban mining more lucrative. The RecEOL project aims to increase the amount of metals reclaimed from e-waste recycling from 70-80%, to up to 95%.

The process will also be the first recycling technology of its kind to capture critical and special metals, such as indium and tantalum from PCBs and LCDs, according to the researchers, which aim to show the process is economically viable and environmentally better than current methods through a pilot plant.

“We know what’s in the urban mine, we just need more innovation in the sector to be able to extract it. The challenge to crack is to extract the metals at a cost that can compete with virgin materials, and to get steady and sufficient quantities of that material so that there’s bankable, predictable process. That’s the next frontier,” says Tech UK’s Baker.