Advocates of big carbon cuts in China have had many reasons for optimism lately. Coal consumption and steel consumption are falling after a long period of overproduction. Hopes are high that carbon emissions will peak soon after an apparent high water mark in coal demand and industrial commodities.

China’s economic slowdown, which has had a disproportionately big impact on heavy industries, could help lower emissions further. And they are further encouraged by China’s commitment to the Paris Agreement on combating climate change last December.

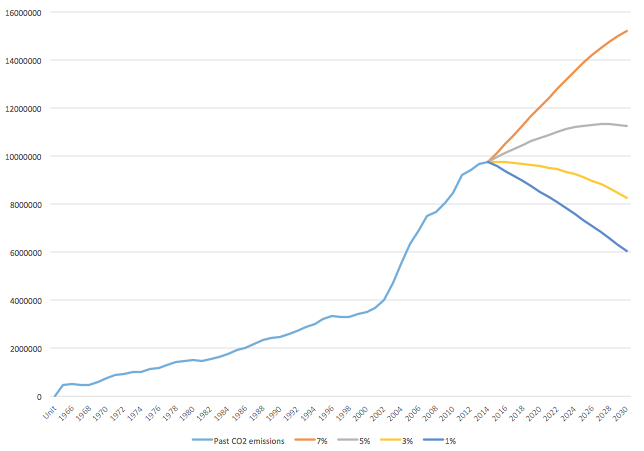

China's historical and forecast CO2 emissions

Yet, expectations of a swift change towards a low-carbon economy in China are premature. Under stable economic conditions, China would be expected, over the long term, to steer its coal-addicted economy toward a new model of low-carbon economic growth. But the very economic slowdown that is stoking expectations of falling emissions could eventually hinder China’s efforts to slow and reverse growth in greenhouse gas emissions.

The immediate effect of the slowdown is a drop in energy consumption and CO2 emissions growth. In the medium to long-term, however, weaker growth will increase the temptation to stimulate short-term growth at the expense of long-term climate goals.

Three scenarios

Three possible scenarios can be drawn for China’s future CO2 emissions under an economic downturn.

In the first, and most likely scenario, which we call “delay”, maintaining growth and preventing unemployment becomes the priority, necessary structural changes to the economy are likely to be postponed. Short-term stimulus through infrastructure and construction would delay the reduction in carbon intensity. In this scenario, even a phase of low growth would be accompanied by a slower but continuing increase in CO2 emissions.

In our second scenario, “backslide”, political pressure to create immediate growth wins out at the expense of emission reduction goals. Driven by short-term fears about an uncontrolled economic downturn, rising unemployment and the connected risk of political crisis, the government primarily tries to generate growth quickly by supporting traditional, highly polluting industries, through investments in infrastructure and construction. Channeling stimulus through these tested methods appears as the “safest bet” to the political leadership.

This backslide scenario mimics past practices. Previous stimulus packages in China have tended to support established industries. For example, the government’s response to the global economic crisis in 2008-2011 was to pour 70% of funds into infrastructure and construction, with devastating implications for coal consumption and CO2 emissions. Despite the environmental cost, the response did produce rapid short-term growth. The temptation to repeat the past is therefore high.

The hope that bolstering heavy industry and construction will stabilise employment is a central driver of the backslide scenario. The sharper the economic downturn, the more urgent a problem short-term unemployment becomes.

In a sharp downturn, the priority is saving jobs within established industries, such as mining, heavy industry, manufacturing, and construction – rather than transferring jobs to emerging and less carbon-intensive sectors such as services and internet-related technologies.

However, these methods are losing their effectiveness. Nearly twice as much investment is needed today to generate the same amount of job growth as in 2008. Job creation in these industries is therefore becoming increasingly difficult.

While these measures might still deliver short-term economic relief, it is unlikely that they can successfully stimulate growth for a prolonged period of time. This ultimately renders the most pessimistic scenario an unappealing option for the government. But even partial developments in this direction could cause a major setback for China’s climate change efforts. China misses its targets of a 60-65% reduction in CO2 intensity by 2030.

Missed opportunities

In an optimistic “acceleration” scenario, China seizes the opportunity of the slowdown for accelerating the transition towards a more sustainable economic structure. The government uses stimulus hasten economic restructuring and rapidly expands less carbon-intensive parts of the economy.

This scenario also earmarks environmental technologies as catalysts for growth. Studies estimate that economic transition could eliminate 2.9 million jobs in energy-intensive sectors, but create 12.5 million new jobs in environmental industries by 2020.

Assuming the acceleration scenario is realised, CO2 emissions will decline rapidly. China will outperform its non-fossil energy and CO2 intensity targets for 2030 and emerges as a driving force of global climate change mitigation.

However, in the context of acute economic slowdown, stimulus measures focusing on a long-term strategy towards green growth seem unrealistic. It would be a high-risk endeavour for the political leadership to base stimulus attempts primarily on untested industries like environmental technologies or the internet economy. Their ability to quickly create growth across the entire economy is uncertain.

Under economic and political pressure, extensive green job creation is rather unlikely as well. It is uncertain whether a rapid transfer of employment into new industries is possible and whether China’s education system would be able to prepare workers for their new jobs in time. It would be a high-risk proposition for the government to place its bets mainly on quick green job creation.

Delay to ‘carbon peak’

The pessimist “backslide” and the optimist “acceleration” scenarios represent the less likely outcomes, whereas the “delay”, a combination of the two, is more feasible.

In this scenario, China’s leadership takes stimulus measures in infrastructure and construction to raise employment levels and steer the economy through the most dangerous phase of any major economic downturn.

Eventually, as the output of these industries decline, the political leadership gradually returns to stimulus measures more in line with a long-term economic transition. But this will delay the long-term process of job transfer into new sectors.

The existing environmental framework prevents a full “backslide” scenario. However, the economic slowdown halts the expansion of new regulations and policies. Willingness to make environmental investments decreases among local governments suffering from high budget deficits and debts. This puts new initiatives, such as the carbon market projected to be rolled out nationally by 2017, effectively on hold.

Under the “delay” scenario, CO2 emissions quickly increase after the initial drop. As China’s government then gradually returns to stimulus measures more in line with low-carbon growth, the emission increase slows down. China eventually achieves a CO2 emissions peak at a high emissions level, but misses the 2030 target.

Afterward, even with low economic growth, absolute reductions in emissions progress slowly as the structural change is continuously disturbed by ad-hoc reactions to economic turbulence. China struggles to make a major contribution to avoiding dangerous climate change.

The years to come are a decisive period

China’s economic policy decisions over the next years will be a crucial factor for making the Paris agreement a reality.

If China’s economic policy breaks free from short-sighted temptations, attempting to achieve an “acceleration” scenario, it can make a major contribution to turn the tide in the global fight against climate change.

But the danger is great that immediate economic necessities will prevail over a long-term vision for China’s economic and ecologic well-being. If China is heading into the “delay” scenario that postpones important economic structural changes and substantial climate change measures, the global climate change mitigation efforts are doomed to fail.

![A one-horned rhino in the grasslands of Orang (left) and a tiger in its wetlands [Images by Forest Department, Government of Assam]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2016/03/Orang_Wildlife_Image_Forest_Department_Assam-300x98.jpg)