The world’s largest privately owned coal producer, Peabody Energy, has filed for bankruptcy in the US, providing yet another sign that much of the world’s production of the fossil fuel – and others including oil – could be economically unfeasible.

Peabody, who five years ago was valued at US$20 billion, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on April 13 after a sharp drop in coal prices left it unable to service a US$10 billion debt which funded its Australian expansion.

It becomes the 50th coal producer, and the largest, to file for bankruptcy in the US in recent years. Divestment campaigners have seized on Peabody’s demise, pointing out that it is another huge setback for an energy source that is the main cause of climate change, and could prompt more financial institutions to ditch investments in the fuel.

The news of Peabody’s collapse had been predicted after its debt troubles began to intensify last year following a forced US$700 million writedown on its Australian metallurgical coal assets, mainly because of a huge surplus of steel in China.

See also: China stokes global coal growth

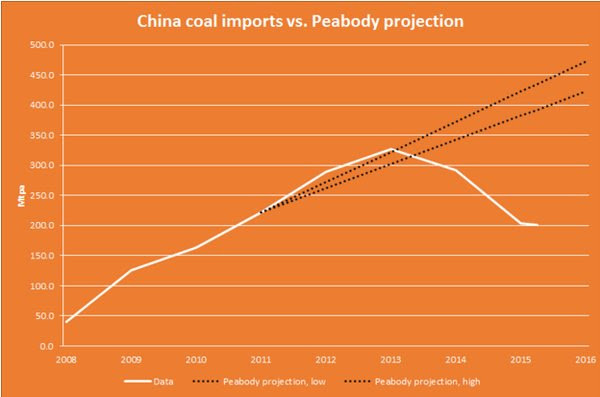

Graphic from Greenpeace

Analysis from Greenpeace says Peabody got it “completely, fantastically wrong” on China’s coal demand.

“A few short years back, the company was projecting a doubling of China’s coal imports from 2011 to 2016 — in reality, the imports are likely to fall back to 2011 levels or below this year, diving more than 40% below their peak in 2013. The difference in the value of the Chinese market is about US$10 billion,” Greenpeace’s coal expert Lauri Myllyvirta said in a blog.

Demand for thermal coal burnt in power stations has slowed sharply in recent years, adding to a major supply glut that hammered futures prices down to 13-year lows around US$36 a tonne in February.

“The demise of Peabody Energy highlights the fundamental structural change which is rapidly reshaping world energy markets as human-induced climate change bites,” said Ian Dunlop, former chair of the Australian Coal Association.

For decades, Peabody was one of the most active in trying to delay, dismantle or prevent climate action, and has been hobbled by two big trends that have made fossil fuels an increasingly risky investment.

Huge oversupply, partly because of major expansions in the past decade of mines and infrastructure in countries such as Australia, China, Colombia and Indonesia, has driven down prices to below break-even for many producers, particularly in the US.

Meanwhile, environmental legislation in countries including China, EU member states and the US to cut carbon emissions and particulates, which cause smog, has prompted closures of power stations and industrial plants that burn coal.

Peabody’s demise could also be regarded as an early example of the financial destruction and ‘stranded assets’ predicted by Bank of England governor Mark Carney if the world shifts decisively towards low carbon energy.

The global ‘Carbon Budget’ – the level of emissions that must not be exceeded to limit global warming to 2C, implied by estimates from the UN’s climate science arm – amounts to between a fifth and a third of the world’s proven reserves of oil, gas and coal.

“The exposure of UK investors, including insurance companies, to these shifts is potentially huge,” Carney said last year.

US ratings agency Moody’s believes that the current coal market downturn which has hastened Peabody’s decline is structural in nature, with weak conditions likely to persist.

“This ends a period of elevated prices that prompted expensive investments, which now look ill-advised,” said a spokesperson from Moody’s Investors Service, adding that some major banks are now refusing to finance coal projects.

Goldman Sachs has said that coal will “never gain enough traction again to lift it out of its slump”.

But many coal assets, particularly in some developing countries, will remain profitable even at these lower prices, ammunition for those who claim that its death has been exaggerated.

However, even if mines in countries such as India and Indonesia remain profitable, many companies elsewhere face an uphill struggle to stay in business.

“Coal will have to innovate in ways that it has not done before. That means smaller markets and fewer mines,” said Tom Sanzillo, director of finance from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

US coal producers face some of the toughest problems as domestic gas prices have fallen sharply, making the cleaner burning fuel more profitable for power generation.

Government legislation is also a factor.

“You also have quite an aggressive stance against coal in the US driven by Obama and various environmental agencies that have also encouraged us to use gas or alternative energy sources where possible,” Hunter Hillcoat, mining analyst at Investec Securities in London, told chinadialogue.

US producers, such as Peabody, haven’t been able to take advantage of weaker currencies enjoyed by other exporting nations, while demand for imported coal in countries such as China and India has been weakening.

The big question now is whether many developing countries, which still plan to build lots of new coal-fired power stations to speed up economic growth, will stand aloof from trends assailing western producers of coal.

Moreover, there are predictions that big oil could go the same way as king coal, particularly if electric vehicles become the norm and a gush of oversupply from the Middle East keeps prices low.