Volvo made headlines earlier this month when it announced that electrification will be “at the core of its future business” and is “paving the way for a new chapter in automotive history”. But while the Chinese-owned company’s commitment to stop producing new vehicles powered solely by internal combustion engines by 2019 is bold, it makes a lot of sense given global trends in the automotive sector, and China’s own ambitions to become a world leader in electric vehicles (EVs).

To shift away from combustion engines, Volvo will introduce a portfolio of EVs across its range that includes fully electric cars, and hybrid cars, which use both battery power and a conventional engine.

“This announcement marks the end of the solely combustion engine-powered car,” said Håkan Samuelsson, Volvo Cars president and chief executive. “Volvo Cars has stated that it plans to have sold a total of one million electrified cars by 2025. When we said it we meant it.”

Julia Hildermeier clean vehicles and e-mobility officer at Brussels-based campaign group Transport and Environment, said: “Volvo’s announcement is quite eye-catching. But when we look in detail it’s not such a surprise. It’s an early announcement of what most car makers will be doing in the next ten years.”

Regulations on fuel-efficiency and carbon dioxide emissions in the US and Europe are pushing automakers to put more efficient cars on the road, and most are moving in this direction, she said. Volkswagen, Daimler and BMW have all announced targets for EVs to make up 20-25% of their fleets by 2025, she noted.

Hildermeier said the shift to electrification is also being driven by an 80% drop in the cost of batteries for EVs in the past ten years and a similar sized improvement in performance. EVs are predicted to be price-competitive with conventional cars by the early 2020s, in terms of the total cost of ownership over four years. “We think we’re now at the beginning of an exponential development of the EV market. By 2050, you can see an almost total electrification of the fleet,” she added.

A bold move

Volvo has been lauded by commenters for taking a bolder position than other brands, which are still manufacturing conventional cars in parallel with electric vehicles and hybrids.

Hildermeier said: “It is a bold statement compared with other car companies. The main reason for this is that Volvo is owned by a Chinese company so they have a very clear technology choice to make.”

Volvo parent company Geely Auto announced in November 2015 that it would shift from internal combustion engine vehicles towards new energy vehicles. By 2020, Geely Auto is targeting 90% of its vehicle sales to be EVs, plug-in electric hybrids and hybrid electric vehicles.

Christian Hochfeld, chief executive of Agora Verkehrswende, a German initiative to decarbonise the transport sector, said that Volvo’s statement goes further than other car companies because it is the first to state that it will not invest any further in the optimisation of the internal combustion engine.

“This means that they don’t see a bright future for combustion propulsion in the medium to long term, which is a very important sign,” he said.

David Tyfield, a reader at the Lancaster Environment Centre at Lancaster University and director of the Joint Institute for the Environment, Guangzhou, does not believe that Volvo’s announcement on its own is enough to swing the market towards announcing similar phase-outs of internal combustion engines, calling it “another drip in a growing stream of transformations in the car industry”.

“It shows some kind of growth in momentum, but I don’t think it signals a tipping point. I don’t think it is likely to precipitate a stampede of other car companies following suit. Volvo is a reputable company but it’s not a rainmaker in the industry [in terms of sales size].”

The reason Volvo was bought by Chinese company Geely in 2010 was that it was not profitable for GM, Tyfield points out. “You could say that Volvo positioning itself as a leader in electric vehicles comes from a position of weakness rather than strength,” he said.

China’s electric ambition

Chinese ownership of the brand has catalysed its decision to phase out production of cars powered only by fossil fuels, Hochfeld maintained. China has ambitions to be a world leader in EVs, with the government’s latest five-year plan setting a target for cumulative sales of electric vehicles to reach more than five million by 2020.

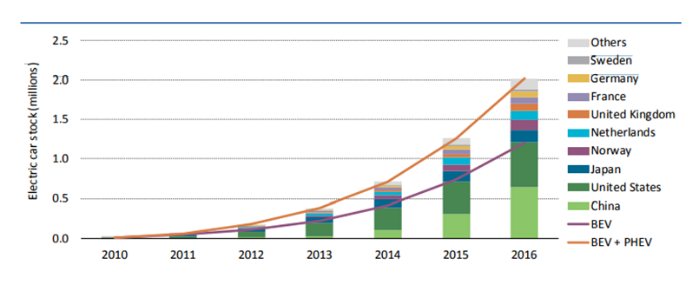

Last year, China overtook the US as the world’s largest market for EVs, with around a third of the global total sales and more than double the amount sold in the US, according to a report by the International Energy Agency.

Global electric car stock, 2005-2016. Source: IEA

Global electric car stock, 2005-2016. Source: IEA

Though it still ranks far below Norway (29%), the Netherlands (6.4%), and Sweden (3.4%) for the total number of electric vehicles in its fleet, the Chinese government is implementing comprehensive policies to boost growth further, including zero emission vehicle mandates (ZEV). Pioneered in California, these require car makers to sell a set portion of ultra-low or zero-emission vehicles. China is aiming for 8% of new car sales to be electric by 2018, rising to 12% by 2020. Rules in place since 2011 place a cap on the registration of new fossil-fuel powered cars.

China has also installed charging infrastructure to address “range anxiety” by potential purchasers of electric cars. The State Grid Corporation of China and China Southern Power Grid together have opened more than 27,000 charging stations. Although critics say this is insufficient, it is still ahead of charging infrastructure in the EU, where member state governments have been slow to deploy charging points, according to Hildermeier.

China is also co-leading the Electric Vehicles Initiative, a multi-government policy forum established in 2009 under the Clean Energy Ministerial, which aims to accelerate the deployment of electric vehicles worldwide.

Domestic pressure to act on air pollution and a clear industrial policy to support electric vehicles have contributed to China becoming a world leader in the technology, Hochfeld said. It has also been a matter of international competition. “The Chinese government and Chinese companies understood that they were lagging behind in the quality of the product in terms of cars with internal combustion engines and they didn’t really catch up with the international benchmark.”

Five or ten years ago there were not many international companies working on e-mobility so they decided to leapfrog traditional technologies and focus on this, he said.

Whether China can maintain this momentum depends on what investments are made in other countries, Hildermeier said. “China has a very comprehensive set of policies to encourage companies and private owners to buy electric vehicles.”

Wider impacts of EV growth

A growth in electric cars must be accompanied by a growth in renewable energy, Hochfeld pointed out. Without this, the benefit of electric vehicles would be limited to their greater efficiency, but they would still be powered by fossil fuels.

There are also implications for electricity grids, which will have to cope with increased demand. Yoann Le Petit, clean vehicles and e-mobility officer at Transport and Environment pointed out that as the share of renewable energy increases, electric vehicles can provide flexibility to grids helping to manage fluctuating supply from renewable electricity sources. EV batteries can be used to send electricity back to the grid when demand is greater than supply.

Ultimately, it will be up to car companies and governments to ensure that policies and business plans on electric vehicles complement each other. “More and more we see the shift to e-mobility as not just an environmental issue but it’s also an industrial decision – the question is can you combine both of these in a way that meets climate goals and that we save the future for jobs and growth, both in Europe and China,” Hildermeier said.