Hurricanes in the Caribbean and deadly floods across South Asia have once again raised the issue of climate justice.

The association between such events and climate change is now beyond serious question: we have had 30 years of well-founded scientific warnings about the relationship between increasing global temperatures and the incidence and severity of extreme weather. Much more problematic is the question of responsibility for climate change itself, and who should justly pay compensation for the resulting damage.

This is complicated, and there are no clear categories of winners and losers, or responsible and blameless. Consider how the benefits from greenhouse gas emissions are usually divorced from the impacts of climate change, yet hurricane-hit Texas owes much of its wealth to oil. Or look at the extraordinary inequalities among those affected by the storms – most are relatively poor, but a few are among the world’s richest people.

The long struggle for ‘climate justice’

International debate on climate justice has usually occurred within the UN, via its Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in a process which led to the Paris Agreement. For much of the time since its inception in 1992 there was a heavy focus on cutting emissions rather than on adaptation to the damaging consequences of climate change.

Responsibility for global warming was usually framed as an obligation for developed states to make the initial moves to reduce their emissions, under the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”. Climate justice was seen as something developed states owed less developed states, and were obliged to deliver so the latter had an incentive to cut their emissions, too.

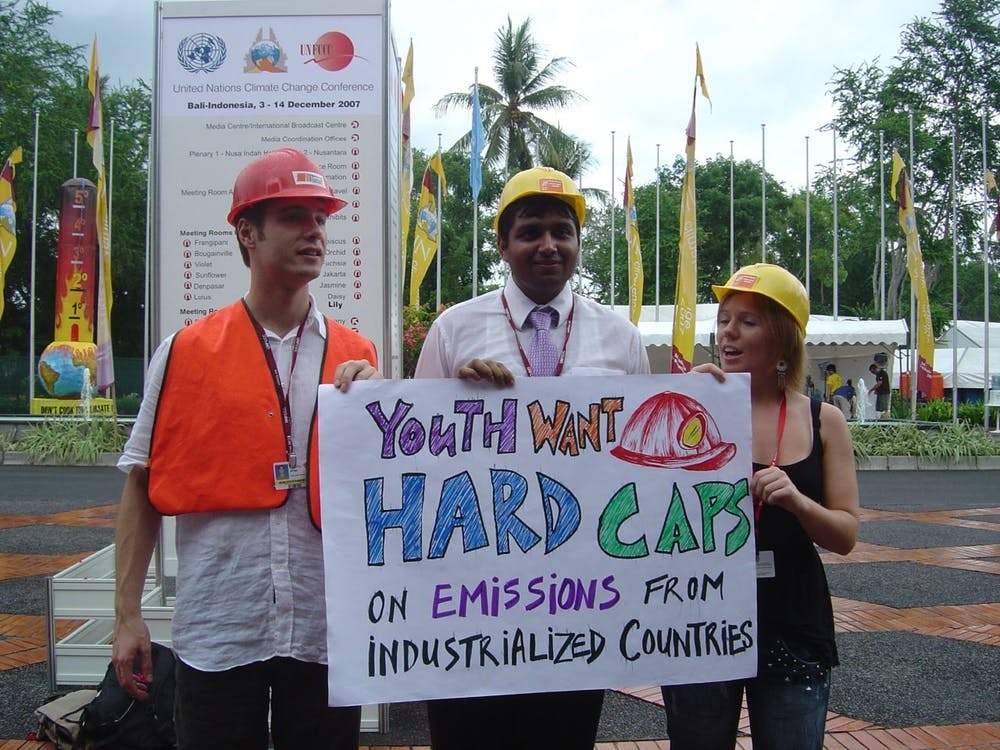

Calls for ‘hard caps’ on emissions at the UN climate conference in Bali, 2007. OpenDemocracy, CC BY-SA

However, by the Bali conference in 2007 it was clear that climate-related sea level rise and extreme weather events were already happening. Adaptation was therefore moved up the agenda alongside emissions cuts. In crude terms, if the developed world wanted a new comprehensive agreement on tackling climate change it would have to provide sufficient guarantees of assistance for the less developed majority. These included a proposed US$100 billion per annum Green Climate Fund but also new form of compensation for “loss and damage for countries vulnerable” to hurricanes and other climate-related disasters.

The “loss and damage” mechanism made it into the 2015 Paris Agreement but has not yet been fully implemented. It was a controversial topic, however, as it raised the question of liability or even reparation for climate damage. Direct responsibility was both difficult to establish and resolutely rejected by developed countries.

Focus on vulnerable individuals

The problem is these issues are discussed within the context of a system of self-interested nation states. Climate change requires a global, concerted effort, yet entrenched political structures within each country reinforce competitive and antagonistic outlooks. It is always difficult, for example, to make the case for foreign governmental assistance when this is ranged against domestic poverty.

To be sure, some of the more progressive rich countries do reflect a “communitarian” approach which recognises some moral obligations to assist vulnerable states. This goes beyond the strict minimum in international law of the avoidance of harm, but it certainly does not admit any direct responsibility or liability. At most, this conception of international climate justice is based upon a recognition that the populations of other countries should not be allowed to deteriorate below minimal standards of human existence and is common to other areas of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

Yet such state-based thinking remains unable to handle the complexity and all-encompassing nature of climate change. What’s needed is an alternative “cosmopolitan” approach to climate justice. Under cosmopolitanism the focus is on individual human beings and their needs and rights, all of whom would exist in one community where nationality is considered irrelevant to moral worth. This means a Bangladeshi farmer or Caribbean fisherman have as much right to be protected from the impact of global warming as someone in Texas or London and, in this sense, cosmopolitan climate justice mirrors the evolution of international human rights principles.

Should protection from flooding be a universal right? Greenpeace / Sataporn Thongma

Nationality is often used to indicate development, or vulnerability to natural hazards, yet such categories are essentially misleading. As illustrated by flooded homes and destroyed roofs everywhere from Barbuda to Houston, it is more useful to think of rich and poor (or safe and vulnerable) people rather than countries.

True climate justice will have to reorientate the debate away from state sovereignty and international standing towards a focus on personal harm. A system of individual carbon accounting would also help so that people make a contribution to poverty reduction and disaster relief appropriate to their wealth and lifestyle.

As hurricanes engulf numerous countries at once, and indirectly affect even more, climate change powerfully illustrates the need for creative thinking about a truly global cosmopolitanism in which the avoidance of human suffering comes before self-interest and it is recognised that there are many poor and vulnerable people in “rich countries” and fabulously rich people in “poor countries”.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation and is republished here with permission.

![View of Pul Doda from the road above, a half submerged structures of a mosque, a temple and a few houses can be seen [image by: Majod Maqbool]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2017/10/A-view-of-the-Pul-Doda-area-from-the-road-above.-The-half-submerged-structures-of-a-mosque-a-temple-and-a-few-houses-can-be-seen-here.-300x184.jpg)