If the climate community had a New Year’s clock hanging in Times Square, it would currently be counting down to 2020. That is when countries worldwide will set new “resolutions”, or nationally determined contributions (NDC) in climate-speak, for curtailing greenhouse gas emissions. But much work remains before the disco ball drops.

The adoption of the Paris Agreement during Conference of Parties (COP) 21 in 2015 marked a historic moment for global climate efforts. The agreement sets ambitious goals to combat climate change and to the limit global temperature increase to 1.5-2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. While a great achievement, it is a new beginning rather than the end of the United Nations (UN) climate process. The agreement compelled governments to submit their own NDCs but left the details of implementation to future negotiations.

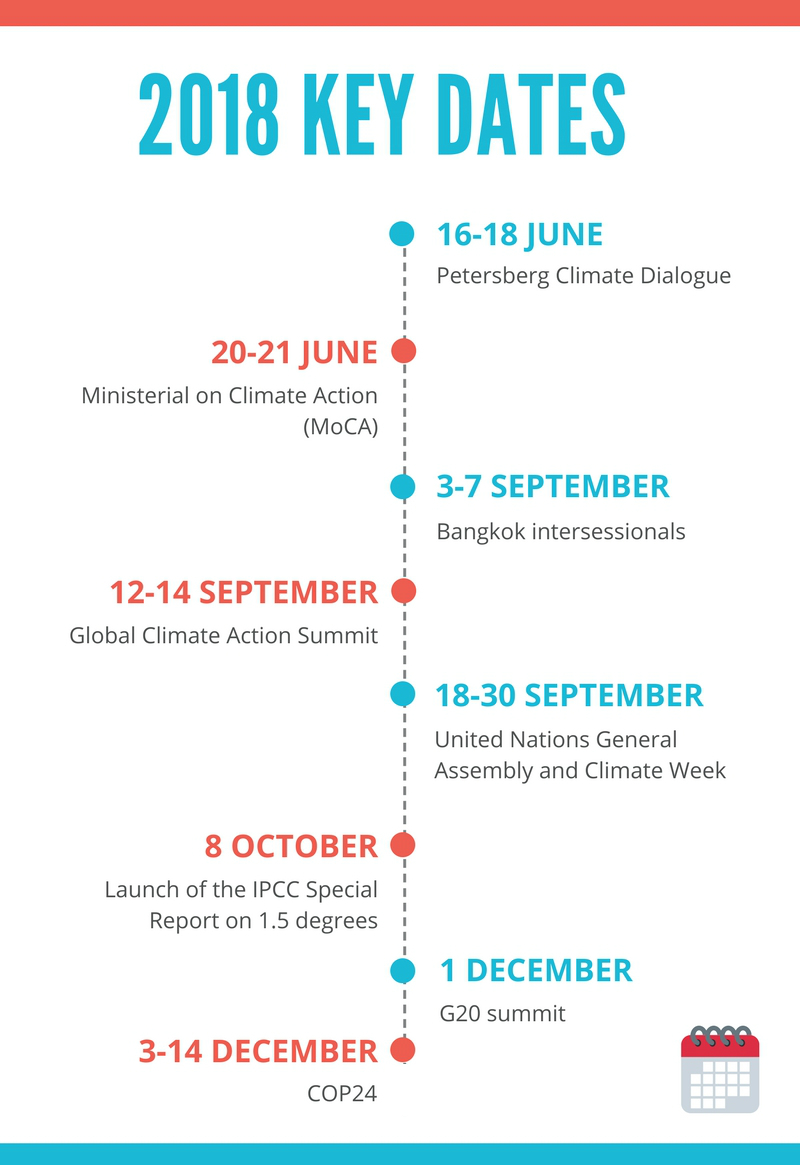

This year countries have to roll up their sleeves and hammer out a “rulebook” for climate action. This makes 2018 the first critical year in the post-Paris era, as countries under the UN framework are required to deliver concrete progress on two key issues: the rulebook and Talanoa Dialogue.

The rulebook

This will provide the operational guidance for the implementation of the Paris Agreement. If we see the ambitious goals set in the Paris Agreement as the destination, then the rulebook will clarify how countries can arrive at their goals collectively, and how each government will fulfil its requirements.

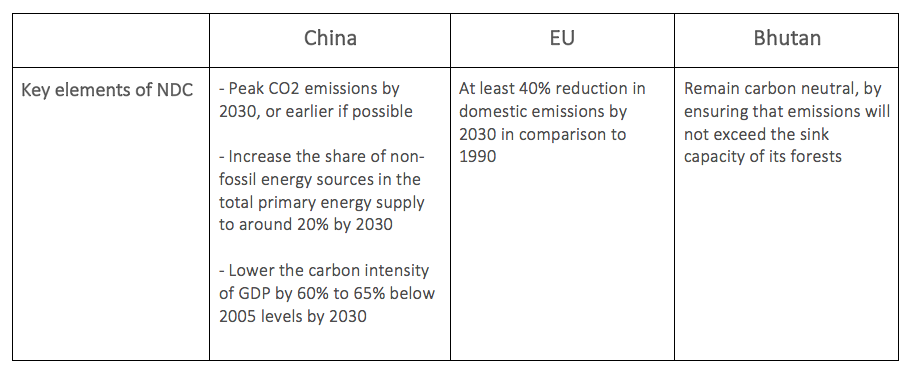

More specifically, the rulebook is expected to provide common metrics so that commitments from different countries can be compared side-by-side. This is necessary because governments submit their NDCs in various formats under the Paris Agreement (see examples in the chart below). The rulebook must also be able to hold all countries accountable and make sure governments’ actions are in line with their words. Finally, it must establish a mechanism that reviews collective efforts and leads to governments scaling-up their actions over time.

Comparing commitments by China, the EU and Bhutan

Climate apples and oranges. Measuring commitments is a challenge without common metrics. Source: Climate Action Tracker

Climate apples and oranges. Measuring commitments is a challenge without common metrics. Source: Climate Action Tracker

At COP22 in Marrakech, the first COP after the Paris Agreement entered into force in November 2016, negotiators set 2018 as the deadline to finalise the guidelines. The rules will be applied from 2020 (since the Paris Agreement covers the period from 2020 onwards).

Under such a tight deadline, overcoming technical challenges and delivering the rules on time is already a huge task, not to mention the political sensitivities around certain issues. For example, as developed and developing countries’ administrative capacities differ, the rulebook must allow for some flexibility while still providing a single set of rules with sufficient rigour.

However, after several rounds of negotiations between technical experts since Marrakech, negotiations opened smoothly at the Bonn intersessional this week, signalling that the challenge now is not whether countries will agree on a rulebook, but to make sure the rules are strong. To achieve this, the discussions need to move from the technical level to the higher, political level, and countries need to show real political will for broader cooperation.

Talanoa Dialogue

Although countries submitted targets for 2025 or 2030 under the Paris Agreement, vulnerable nations are calling for an increase in ambition and actions now. At COP21, countries agreed to take stock of the overall progress on their actions in 2018 for the first time, and to use the assessment to identify how they can scale up their NDCs by 2020 (countries are expected to ratchet up their internal targets every five years under the Paris framework).

Such a process was initially called the Facilitative Dialogue but it was renamed the Talanoa Dialogue at COP23 when Fiji held the presidency. Talanoa is a term in Fijian that means to tell a story or have a conversation. The Talanoa Dialogue process was launched at the beginning of this year, and countries submit their actions via an online public portal.

At the Bonn intersessional, the Talanoa Dialogue will offer a platform for countries and non-party stakeholders to showcase their progress towards a low carbon economy in all kinds of sectors and inspire each other while at the same time demonstrating the risks of inaction. Most countries referenced the dialogue in their opening statements, and over 130 countries have made submissions to the Talanoa Dialogue.

As the name suggests, the current process is inclusive and emphasises the storytelling approach, but it lacks clarity in terms of outcomes. Countries need to make sure their discussions are solution- and future-oriented so that dialogues can be useful in increasing ambition.

The march to 2020

The impact of Talanoa Dialogue will only be fully revealed in 2020 when all countries are supposed to submit their updated targets under the Paris Agreement. As the graphic below shows, current country commitments are still far too unambitious to remain within the safe temperature boundaries set under the Paris Agreement.

Source: UN Environment 2017 Emissions Gap Report

Source: UN Environment 2017 Emissions Gap Report

Alongside the rulebook and Talanoa Dialogue, a series of key events over the next two years will lay the groundwork for countries to increase ambition by 2020. Technical negotiations to secure the rulebook and sort out thorny issues, such as how to compensate countries for losses and damages that result from climate impacts, are underway at the Bonn intersessional. The annual UNFCCC COP negotiations will take place in Poland in December, marking the deadline for the rulebook and Talanoa Dialogue.

Meanwhile, politicians and officials will engage in climate diplomacy outside of the UN cycle. In June, country representatives and ministers will gather in Petersberg, Germany for discussions, and Brussels, Belgium, for a “MoCA” (Ministerial Meeting for Climate Action). In recent years, these meetings have served as key moments for more ambitious countries to form alliances, such as when Canada, the EU, and China together reaffirmed their commitment to climate action in the wake of President Trump’s attack on climate action last year.

Canada, China and the EU announced last year that they would improve cooperation on climate action. Canadian minister of environment and climate change Catherine McKenna is pictured with Chinese special envoy Xie Zhenhua and EU commissioner on climate action and energy Miguel Arias Cañete. Source: Catherine McKenna/Twitter

Canada, China and the EU announced last year that they would improve cooperation on climate action. Canadian minister of environment and climate change Catherine McKenna is pictured with Chinese special envoy Xie Zhenhua and EU commissioner on climate action and energy Miguel Arias Cañete. Source: Catherine McKenna/Twitter

New summits, such as this September's Global Climate Action Summit hosted by Governor Brown in California, will provide opportunities for national, sub-national, and non-state actors to come together. This summit reflects an upside of Trump’s threat to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement: climate action has become more inclusive of a broader array of parties such as businesses and states rather than just national governments.

Another notable moment will be the G20 held in Argentina just before this year’s COP in December. While the G20 agenda extends far beyond climate change, it has become an important platform to discuss green finance issues in particular after China launched a working group on the topic in 2016. The G20 also serves as an important moment of reckoning for how other top nations treat the US, including the degree to which they accommodate the Trump administration’s climate stance.

The jockeying that occurs at these meetings will influence the outcome of the UN negotiations and ultimately determine the level of ambition countries bring to the table. These summits, especially heading into 2019, will also provide opportunities for countries to signal or announce their new commitments. All eyes will be on the world’s top emitters to close the ambition gap as 2020 nears.