To help them prosper in the twenty-first century, a group of about 70 advanced and emerging economies in Asia, Africa and Europe has planned infrastructure investments worth an estimated US$6 trillion. These countries don’t want high-carbon, twentieth-century infrastructure. More and more of them are making it clear through their national climate plans that they want modern, sustainable, climate-resilient solutions.

The need to fill this infrastructure gap is one of the most important economic and business opportunities of the century. But who will capitalise on it?

The Chinese government, for one, has made it clear that it wants its financial institutions and companies to play a leading role. In May 2017, the Chinese government pledged US$113 billion in “special” government funds to encourage its banks and enterprises to invest in Africa, Asia and Europe under its “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI).

China can play a massive role in meeting green infrastructure needs worldwide, but only if it can align its financial flows with low-carbon investments in BRI countries.

Sizing up the opportunity

To understand the scale of the investment opportunity for China, it is helpful to put some numbers on the table. World Resources Institute recently collaborated with colleagues at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center to examine BRI countries’ national climate plans, or “Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)” submitted as part of the international Paris Agreement on climate change. Of all the NDCs, we focused on the 31 that contain quantitative targets and estimated the financing required to meet them.

Our research teams found enormous opportunities. Those 31 countries alone will need about US$470 billion just to implement renewable energy commitments. About half of that would finance solar photovoltaic (PV) projects, and 40% would go to wind and hydropower.

Source: World Resources Institute

We estimate that much of this financing will be in the form of debt, generating major opportunities for banks, and that meeting the solar PV commitments alone will require as much as US$190 billion in debt financing. There will also be room for equity investors; as much as US$100 billion in equity investments will be needed to meet the solar and wind targets.

Quantifying potential investments in the BRI region’s transportation sector proved more difficult, as the NDCs generally lack detailed information. But here, too, the commitments suggest major investment opportunities. Twenty-four BRI countries included transportation infrastructure in their NDCs, including metro and bus lines, railways (both high-speed and traditional) and new roads to reduce congestion. According to an International Finance Corporation study that used a different methodology, private, low-carbon opportunities in the transportation sectors of 17 BRI countries amount to US$2.4 trillion from 2016 to 2030.

In both the cases of energy and transport, the underlying message is clear: countries’ Paris commitments are generating substantial investment opportunities in low-carbon infrastructure.

More brown than green

Chinese finance may well play a key role in filling this financing gap. Indeed, the Chinese government has made clear through several high-level documents and policy pronouncements that it wants BRI investments to be environmentally sustainable.

However, we found that the actual flow of Chinese investments so far has not always matched this ideal. Chinese banks and equity funds will have to get considerably more comfortable with – and more adept at – financing low-carbon solutions abroad if they are going to contribute to a “green” BRI. Chinese capital can do much better at financing sustainable pathways, in collaboration with the BRI countries in which the investments will take place.

A few data points are instructive. Between 2014 and 2017, six Chinese banks (the China Development Bank (CDB), the Export-Import Bank of China and the “Big Four” state-owned commercial banks) participated in US$143 billion worth of syndicated loans to the BRI region’s energy and transportation sectors. Almost three-quarters of the total volume of this finance went to the oil, gas and petrochemical industries. Of the finance that went to the power-generation sector, more than half financed fossil fuel power plants, including US$10 billion for the coal plants.

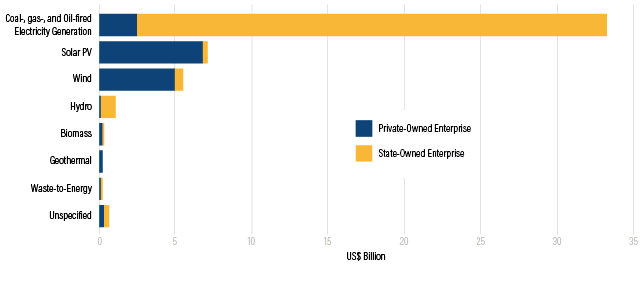

Greenfield investments and M&As by Chinese corporations in the power generation and transmission sector by ownership in 56 BRI Countries (2014-2017)

Greenfield investments involve a parent company building a subsidiary company to conduct operations in a foreign country. Source: WRI. Ownership information is obtained from publicly available sources.

Over the same period, CDB and the Export-Import Bank of China also provided US$45 billion in direct loans to the energy sectors of BRI countries. More than 40% of that finance went to oil, gas, and petrochemical projects. Of the loans that went to power generation, coal-fired plants received the most lending, about a fifth of the sector’s total.

Our study also examined investments by Chinese corporations. In electric power generation and transmission, Chinese enterprises invested mainly in new power plants, rather than in acquiring existing ones. Chinese state-owned enterprises invested overwhelmingly in fossil fuel power generation; virtually all investments in the sector between 2014 and 2017 went to fossil fuel plants.

Interestingly, Chinese privately-owned enterprises behaved differently. They invested heavily in solar PV and wind power, reaching US$7 billion and US$5.5 billion, respectively, over the four-year period. Still, privately-owned firms were no match in terms of financing volume to their much larger state-owned counterparts.

Will China seize the opportunity?

While China’s financial flows to BRI countries have been more brown than green, there are a few ways Chinese financial institutions can change course.

For one, the Chinese government should require entities receiving special government funds to consider NDCs when developing their investment strategies. The multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, have already started doing this. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has also expressed support for aligning investments with member countries’ national energy plans, including NDCs.

When allocating special funds, the Chinese government should also ask the relevant financial institutions to design instruments or funds that address specific green financing barriers in the BRI region in a way that leverages their comparative strengths. For example, the Silk Road Fund, a private-equity fund financed with China’s foreign-exchange reserves, may be better positioned than other institutions to provide early venture capital funding to green enterprises.

BRI country governments have a role to play as well. BRI-country authorities would be well-advised to update their NDCs with sufficient granularity and quantitative information, so investors can understand the future path of government policy and national infrastructure priorities. More broadly, national authorities should incorporate NDCs into their economic assistance and investment dialogues with all international partners. This will send a clear signal to banks and other investors – Chinese or otherwise – that their countries offer major investment opportunities in green technologies and projects.

Chinese financial institutions are well-positioned to help finance the largest expansion of sustainable, climate-resilient infrastructure in history. The only question is whether they will seize the opportunity.

This article was first published by the World Resources Institute

![The sea ice and mountains in Spitsbergen, Svalbard during the Arctic summer [Image by: Josh Harrison/Alamy]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2018/11/arctic-summer-sea-ice-300x200.jpg)