An unusually intense May wildfire roared into Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada, last week, forcing the largest wildfire evacuation in the province’s history. The flames rode the back of hot, windy weather and only a last-minute change in wind direction spared most of the oil town from the flames.

The wildfire is the latest in a lengthening lineage of early wildfires in the northern reaches of the globe that are indicative of a changing climate. As the planet continues to warm, these types of fires will likely only become more common and intense as spring snowpack disappears and temperatures rise.

“This (fire) is consistent with what we expect from human-caused climate change affecting our fire regime,” Mike Flannigan, a wildfire researcher at the University of Alberta, said.

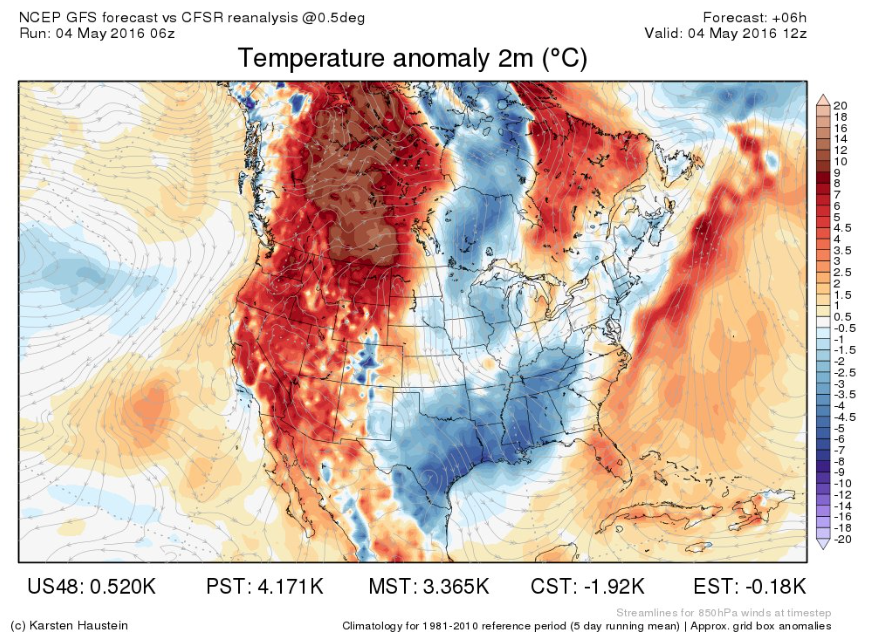

At least one neighbourhood of the northern Albertan city of 61,000 has been nearly entirely razed as the blaze last week ripped through the city from the west. Temperatures soared to almost 35C — up to 22C above normal for this time of year — coupled with high winds helped fan the flames. That sent 80,000 people in the city and surrounding area scrambling north and south through a post-apocalyptic landscape of trees lit up like matchsticks and flashing emergency lights.

People fled the fire using the one road in and out of town even as flames licked the side of the pavement and pea soup-thick smoke turned a daylight drive into one that felt more like dusk.

“You just couldn’t see two feet in front of your truck through all the smoke,” Fort McMurray resident Dan Bickford told the Globe and Mail newspaper from an evacuation centre in the nearby town of Lac La Biche.

The footage evacuees captured is reminiscent of California’s Valley Fire last year, which flared up under similar conditions and destroyed roughly 2,000 buildings in Lake and Sonoma counties.

Despite the harrowing escape for many Fort McMurray residents, not a single fatality has been reported.

Fort McMurray fire chief Darby Allen told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation that Tuesday was the worst day of his career as firefighters scrambled to combat the wildfire. Preliminary reports indicate that 80% of the homes in one neighbourhood have been destroyed, though the full extent of the damage isn’t fully known yet. And it may very well not be over as hot, dry conditions are expected again on Wednesday.

What’s happening in Fort McMurray is a perfect encapsulation of the wicked ways that climate change is impacting wildfire season. A drier than normal winter left a paltry spring snowpack, which was quickly eaten away by warm temperatures. That left plenty of fuel on the ground for wildfires to consume.

Add in the soaring temperatures, and you have a clear view of how climate change is affecting wildfire season, not just in Alberta but across the northern reaches of the globe.

Boreal forests are burning at a rate unprecedented in the last 10,000 years.

See also: California’s wildfires spark debate about water management

A Climate Central analysis of Alaskan wildfires last year showed that the season is 40% longer than it was 65 years ago. Large wildfires there have also doubled over that time.

In Canada, wildfire season now starts a month earlier than it used to and the average annual area burned has doubled since 1970, according to Flannigan.

Climate change has been altering background conditions, but this year’s El Niño also likely played a role in this particularly severe start to wildfire season in western Canada. Following the 1997-98 super El Niño, western Canada experienced a particularly severe wildfire season.

“In this part of the world, El Niño means warm and dry. We’ve had a warm and dry winter and now a warm and dry spring,” Flannigan said. “If I was putting odds on it, odds are we will have another bad fire season.”

When these fires reach cities and towns, the results are devastating. In Fort McMurray, which was the hub of the Canadian tar sands boom that has since quietened with the collapse of oil prices, the economic cost could reach hundreds of millions of dollars, if past fires are any indicator.

But wildfires like this can also wreak havoc on the global climate, too. Boreal forests contain nearly 30% of all the world’s carbon stored on land. As they light up, they send that carbon into the atmosphere where it warms the globe.

Intense wildfires are already turning some forests into carbon polluters in certain years, creating a feedback cycle that drives temperatures higher and raises fire risks even further.

Scientists are also concerned about the vast stores of peat in the boreal forest that spans Alberta and other parts of Canada. That peat contains significant amounts of carbon and once it catches fire, it’s exceedingly hard to put out and can smoulder for weeks or months. It can even survive winter cold to re-emerge in the spring.

That makes living in the woods an increasingly perilous proposition. And it also means that what happens in the forest is unlikely to stay there.

The original version of this story was published on climatecentral.org and can be found here