China’s carbon emissions could fall to 43% of their 2010 level by 2050, simply by persuading its newly affluent consumers to spend less flashily, or guiding them towards modest habits through government policies, according to the latest Annual Review of Low-carbon Development in China (2015-16).

The report, published by Tsinghua-Brookings Center for Public Policy, predicts two starkly different outcomes, depending on which growth models China pursues.

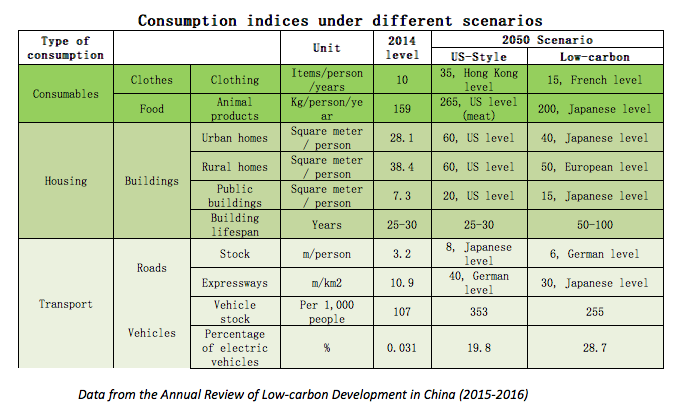

The report’s authors examined how China’s energy consumption and carbon emissions would fare under two options, loosely described as the US “big house, big car” high-carbon consumption lifestyle, versus the “European and Japanese model.”

The authors considered the latter more open to cutting unnecessary products and services, and to consumer goods with longer lifespans.

In the US-style scenario, China would not reach peak carbon until 2030 and energy consumption would be twice the 2010 level by 2050.

By contrast, the more moderate Europe-Japan model would mean total energy consumption of 4.63 billion tonnes of standard coal equivalent (tce) by 2050, assuming normal technological progress. This is 280 million tce less than under the high-consumption scenario.

Carbon emissions would fall 43% by 2050 from a 2010 baseline.

Saving 280 million tce through lifestyle choices offers more than three times the possible reductions than by relying on technological progress alone, the report argues.

“Do we need 60 square metres of housing per person and two cars per household? Or 40 square metres, like in Japan?” asks Dong Wenjuan, a researcher with the Tsinghua-Brookings Centre who contributed to the report.

Big homes and cars

Nonetheless, it will be a hard message to sell to consumers who have been promised visibly greater prosperity as their major measure of personal, and national, progress for more than three decades. For most Chinese, the answer to Dong’s question would be yes, they do.

“A big comfortable house would make me feel safe,” says Meng Qingfang, a migrant to Beijing from Shandong province. She dreams of a three bedroom home, with a lounge and all mod cons. Her friend agrees – if you have the money, of course you’re going to buy a big home. She would consider second-hand appliances, but definitely not second-hand clothes. Charity shops and vintage fashion styled from used clothing are common in the West, but virtually unknown in China.

Daily life – our consumption and lifestyle choices – often involves hidden carbon emissions. Buying one new garment a month or running air-conditioning for an extra 30 minutes a day might seem minor, but the carbon released in making clothes or power-generation adds up.

Policies needed to change habits

The only effective way to make such changes is through government policies reshaping consumer choices, according to speakers at the report’s launch in March. “Structural change cannot occur without strong, enabling policies such as carbon and pollution taxes and the abolition of fossil fuel subsidies,” said keynote speaker Lord Nicholas Stern of the London School of Economics.

He warned the coming two decades would be a crucial period for achieving these changes, “a climacteric for climate change.” Brookings-Tsinghua Center director Qi Ye spoke of “a new normal”.

The message is timely, as China’s national policy goals for the next five years include fostering consumer-led economic growth, yet cutting carbon emissions to reduce deadly smog and halt climate change.

What’s more, the middle class is growing rapidly, along with urbanization. Zou Ji, deputy head of the National Centre for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation told a recent meeting in Beijing that the middle classes are China’s main consumers, and if this group reaches 30-40% of the entire population its consumption will have a significant impact on China’s carbon emissions. At present China’s middle class represents around 30% of urban households.

Consumption habits are not easily changed once formed, he warned.

State policies to encourage low-carbon energy-saving habits are vital, and “much easier than making changes after habits are already set,” says Li Huimin, a member of the research team and the faculty of Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture.

Consumerism

Some central government bodies have begun calling for more modest lifestyles – for instance, the Ministry of Health in June urged people to eat less meat. Although mainly intended to tackle obesity and diabetes, the move was warmly welcomed by environmental campaigners for its potential to reduce levels of methane, a greenhouse gas.

China is already a consumer society, with high levels of production, consumption and waste. Detached houses and powerful cars are popular among the elite; driving holidays, seen as emblematic of US recreational choices, are now accessible to those on average salaries.

One survey found that over half of respondents had changed their phone three times in the last five years, and want to continue doing so.

Tyrene White, associate professor at Swarthmore College, told chinadialogue that even in the US, where most middle class people tend to drive everywhere, lifestyle changes are gradually taking hold. She believes greater public awareness could take three generations to change lifestyles significantly.

However, Lydia Marie, a young American living in China, is trying an extreme ‘zero-waste’ lifestyle for one year. She buys nothing packaged, carries water when she leaves home, avoids buying clothes, and composts kitchen waste to grow vegetables. Her waste for three months fits into two small containers.

Lydia Marie, and the waste she produced in three months – medicine bottles, airline luggage tags, bank slips, shopping receipts, tickets from a trip to the US, the labels from second-hand clothes she bought, and a plastic straw she accidentally used. Photo: Zhang Chun.

Lifestyle changes need policy support

When researching low-carbon lifestyles, the report’s authors looked at standards in different countries – all of which remain aspirational. “Differing national circumstances can mean that what looks feasible is actually very difficult, ” says Dong, adding it is helpful to look at the strengths of different countries.

The Annual Review of Low-carbon Development in China looked at energy consumption under three different scenarios. The baseline scenario is US-style consumption; a 2050 scenario based on US-style consumption combined with technological breakthroughs; and a 2050 low carbon or moderate consumption scenario.

“The situation in smaller countries is simpler, while China has huge regional differences,” said Li Huimin. East China’s population already enjoys mid- to high-level incomes, while in west China incomes in many places are far below the national average.

Current research is generating a stronger consensus on the importance of consumption in cutting carbon emissions. What is urgently needed now is appropriate guidance and policy, said Li.

Signs of change

There are hopeful signs. Earlier this year the National Development and Reform Commission, jointly with the Party Publicity Department, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, the China National Tourism Administration and the National Government Offices Administration published a document on promotion of green consumption.

It listed 17 tasks, including the creation of regulations on excess packaging, a revision of the Law on Promotion of the Circular Economy, and encouraging businesses to offer more green products and services, with the aim of creating a consensus on green consumption by 2020 and establishing green low-carbon lifestyles and consumption styles.

And society is quietly changing. Many people are now used to the “clean plates” campaign, which sees restaurants offer smaller portions of food, and public bike hire schemes are becoming more popular.

Businesses are contributing – 32 delivery firms, including China Post, Canada Post and Fedex, are aiming to replace 50% of packaging with entirely biodegradable materials by 2020 and to avoid 3.62 million tonnes of carbon emissions through the use of new energy vehicles, recyclables, and reusable packaging.

Li says achieving the low-carbon scenario modelled will not be easy, but “If there’s a will to act and policies are put in place, it is achievable.”