When super-typhoon Meranti made landfall on September 15 in the Xiang’an district of Xiamen, it was the strongest typhoon to reach land anywhere in the world this year, and the strongest ever to hit the Fujianese mainland.

“Everything in the room was blowing about, even the duvet!” said Cai Lingting, who lives near the sea on the east of Xiamen.

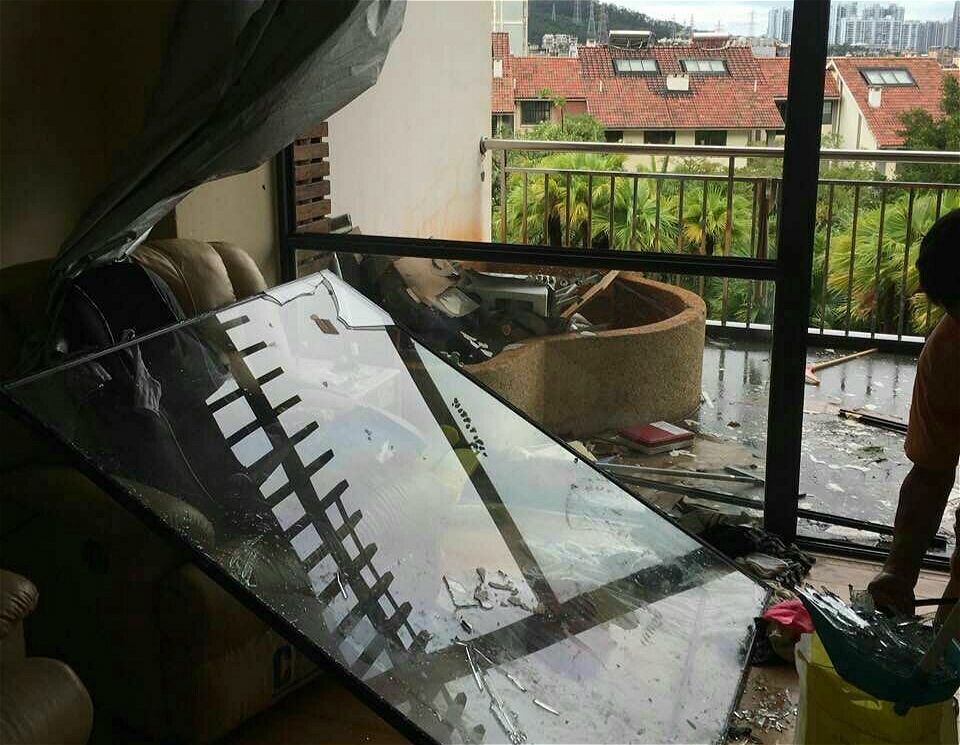

The typhoon shattered two of her glass windows, damaged furniture and other items, and left the room sodden. The windows will be replaced by the apartment complex’s managers, and Cai’s worker’s union will provide some compensation, although Cai hasn’t asked for any. She’ll cover the other costs herself.

Meranti left 28 dead and 15 missing across Fujian province and neighbouring Zhejiang, and caused 20 billion yuan (US$3 billion) in damage. Half of this – totalling 10 billion yuan (US$1.5 billion) – was in Xiamen. That’s the equivalent of one sixth of the city government’s annual income. A total of 17,000 buildings collapsed, mostly workshops and factories. Agriculture was also hit badly. The livestock sector suffered losses of 900 million yuan (US$133 million) and 105,000 mu of crops were lost or damaged.

Damage from super-typhoon Meranti in Xiamen. (Image from weibo)

Is climate insurance needed?

Climate change is expected to increase the likelihood and severity of typhoons. Summer temperatures hit record highs this year, and rising sea levels may worsen the effects of flooding when typhoons make landfall. But despite the enormous losses that people can suffer when a typhoon landfalls, the climate insurance market in China remains nascent.

This could be about to change. The government plans to establish an insurance system to deal with climate-related hazards, and in August, the People’s Bank of China and seven other government authorities released a paper on building a green finance system.

Guo Peiyuan, general manager of SynTao Green Finance, a sustainable finance consultancy, said the government is right to encourage action on climate insurance. He told chinadialogue that the majority of insurance firms have a limited understanding of climate change and ‘green insurance’, and that the insurance industry has been slow to acknowledge the importance of sustainable development.

“Whenever we talk about environmental issues with Chinese insurance firms, they just bring up pollution liability insurance,” he said, referring to the obligation companies have to buy insurance if their operations pose a high environmental risk.

Insurance penetration is very low in China, and many insurance firms do not provide cover for risks such as typhoons. However, Guo pointed out that efforts to expand climate insurance cover must be coordinated by the state. “Those policies must then be reinsured, and purely commercial operations cannot cover the costs of a huge natural disaster,” he said.

Local governments are already piloting climate insurance schemes in some areas to address risks faced by the agricultural sector from typhoons. In Fujian, for example, the local government is trialling insurance for agricultural buildings, with pay-outs of up to tens of thousands of yuan, either in part or in whole. The scope and coverage of these policies is limited though, according to Guo. The problem, he said, is that insurance companies aren’t looking at typhoons as a climate change issue.

In the agricultural sector, the most relevant type of insurance policy related to climate change in China is called climate index insurance. Instead of determining pay-outs on the basis of damage and loss, policies are based on a weather index that sets compensation levels based on different weather conditions, such as rainfall. For example, if rainfall exceeds a particular threshold then insurance would automatically pay-out.

In January the State Council used its first communique of the year to announce trials of this approach in the agricultural sector. The development of the index will involve a number of different departments and is still in its early stages. In March, the China Property & Casualty Reinsurance Company, the China Agricultural Insurance and Reinsurance Union and the China Meteorology Administration explored using data from weather stations as the basis for deciding on insurance pay-outs, to make climate index insurance more reliable.

Addressing climate risks

Climate insurance is already used widely elsewhere. Japan is often hit by typhoons and has had typhoon insurance included in residential property policies since the 1960s. Like climate index insurance, climate insurance policies have led to changes in the risk management mechanisms used by the insurance industry.

Although the Chinese industry has few climate insurance products, it has long been aware of climate risks. In 2010 the People’s Insurance Company of China established a disaster research centre to carry out basic research into disasters, and theoretical and applied research into disaster management, in order to improve risk management.

China isn’t alone though in responding slowly to the challenge of incorporating climate risks into insurance products. Julian Poulter, CEO of the Asset Owners Disclosure Project, a non-profit that helps asset owners respond to climate change risks, said, “Climate change poses a double threat to the insurance industry. Insurers face mounting costs from claims relating to the impacts of climate change, and the investment portfolios that enable them to meet those claims are exposed to climate risks as the transition to a low-carbon economy accelerates.”

Global losses due to natural disasters stand at US$70 billion for the first half of this year, a significant rise on last year, which means insurers are facing an increase in claims. At this year’s G20 summit a number of global insurers called for G20 nations to plan for eliminating fossil fuel subsidies in order to mitigate the effects of climate change.

But a July report from the Asset Owners Disclosure Project claimed that insurers are doing too little to address climate risks in investment portfolios. Insurance companies control one third of the world’s investment assets, but the report found that just one in eight insurers are taking tangible action to manage climate risk, compared with one in four pension funds. This is both a growing risk and a missed opportunity for insurers. Currently, just 0.2% of insurers’ investments are in the low-carbon sector. And two fifths of insurers are taking no action to protect their portfolios, exposing US$4.2 trillion to climate risk.

Poulter said that if insurers face significant losses to their investments as a result of climate change, it will reduce their long term capacity to cover future claims and put clients’ policies in jeopardy. Given that few insurers are taking action, there is a serious risk of systemic failure which could have catastrophic effects on the wider economy.