If Angela Merkel is to win another term in Germany’s upcoming election on September 24, then winning the western state of North-Rhine/Westphalia (NRW) will be essential.

NRW is the country’s most populous state, making up a fifth of the electorate. It’s also the epicentre of another political tussle: What to do about Germany’s coal sector?

The state is the historic heart of Germany’s industry; an industry that is largely powered by coal. NRW sits atop Europe’s biggest lignite coal region, and despite Germany’s rapid adoption of renewables, NRW still generates 75% of its electricity from coal, making it responsible for almost 1% of global annual greenhouse gas emissions.

So it’s no surprise that the Rhineland coalfields near Cologne have become a hot spot for climate activists in the past few years. As recently as August, thousands of people blocked train tracks and roads between the coal mines and power plants. The activists recognise that blocking trains won’t stop the industry but see the symbolic nature of the protests as important.

“Our powerful protests have put climate justice on the political agenda,“ said Janna Aljets, spokesperson of the “Ende Gelände” campaign, which translates literally as “the end of the terrain”. “Coal no longer has public acceptance,” she added.

Coal country

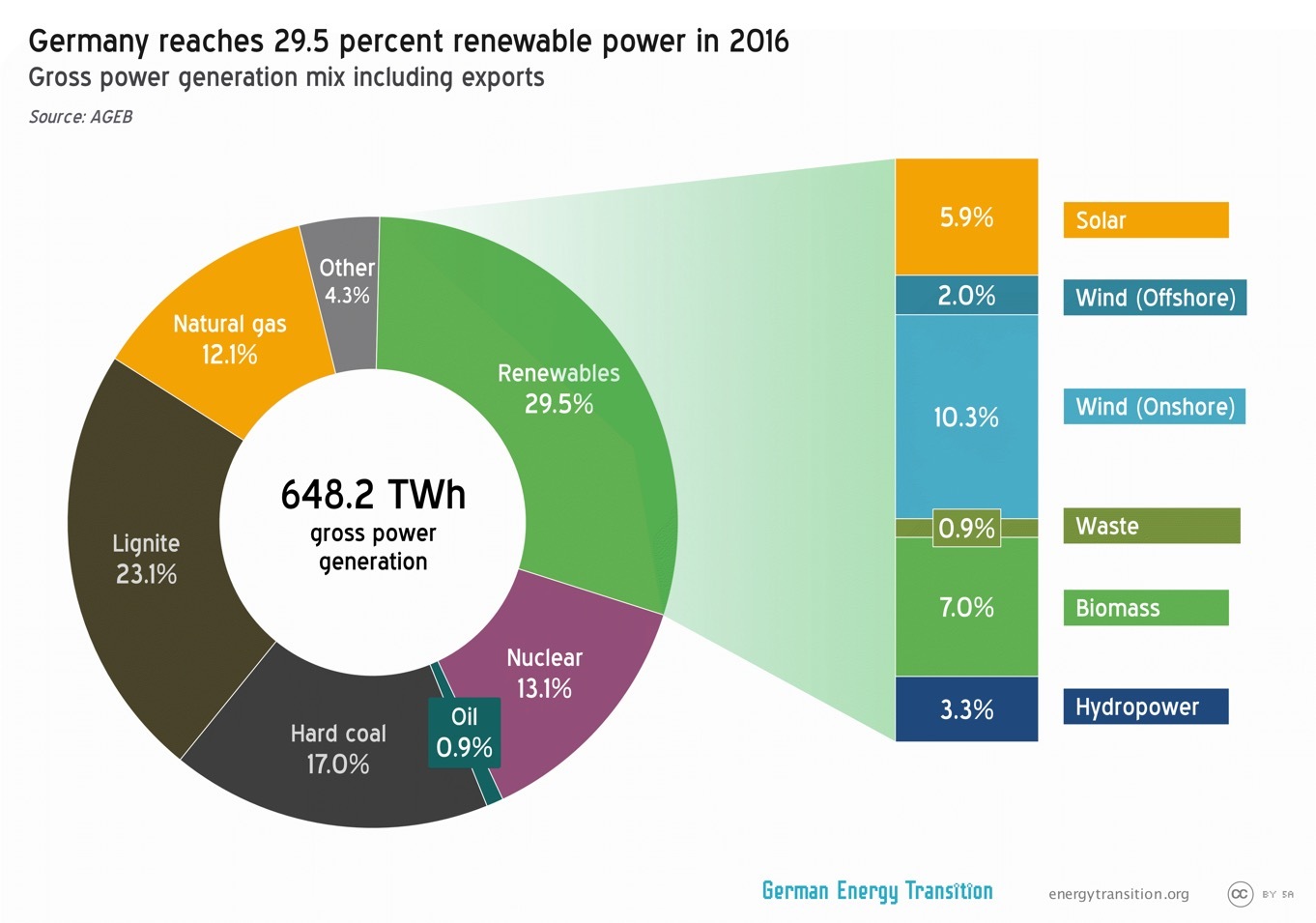

Internationally, Germany is well-known for its Energiewende energy policy, a transition away from nuclear and fossil fuels to renewables. But despite the aggressive push toward renewables, coal remains central to Germany’s power supply. In recent years, electricity production from coal has hardly fallen, unlike in other developed countries such as the UK and US. In fact, lignite coal provided 23% of gross power production in 2016, and hard coal 17%.

Some critics argue that coal still dominates Germany’s power generation because the country has chosen to phase-out nuclear power, with the remaining plants to shut by 2022. In the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster in Japan, around a dozen new coal plants opened in Germany.

What’s missing from reports about the alleged “German coal renaissance” though is that Germany’s coal surge was part of a Europe-wide trend, and not just a reaction to the nuclear phase-out. Construction of many of the plants started long before the meltdown in Fukushima.

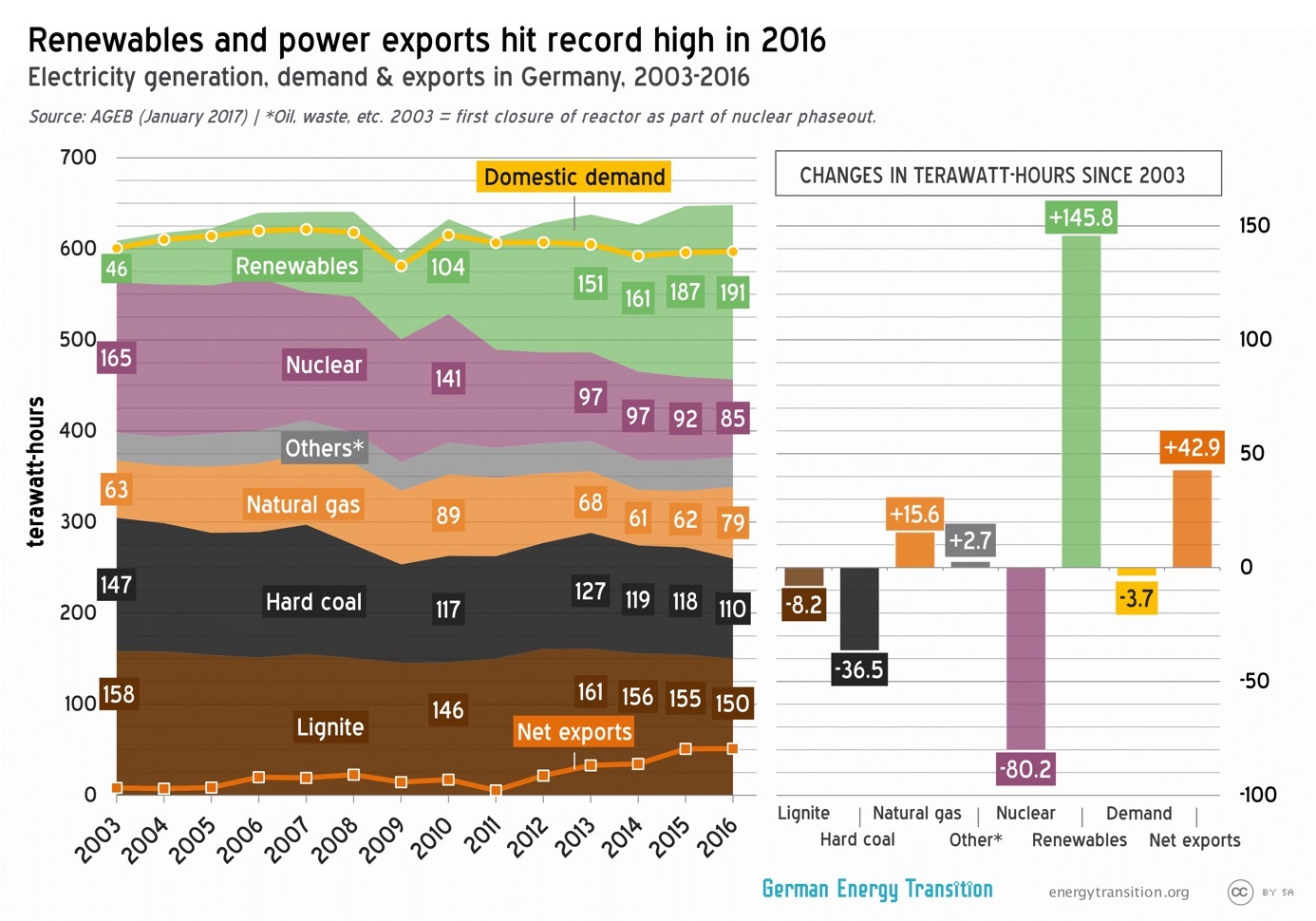

German utilities began abandoning coal projects around 2011 for the simple reason that there was no demand for them. By then, it was clear that renewables growth had been underestimated. Investors cancelled two dozen projects. The surge in wind and solar power combined with on-going coal power production led to an oversupply of electricity. As a result, power exports hit a record high by 2016. Almost 8% of electricity generated in Germany last year was used in neighbouring countries.

These developments have led to the so-called “Energiewende paradox”: Germany’s rapid development of renewable power has barely dented carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions even though electricity generated from renewables has more than replaced nuclear power.

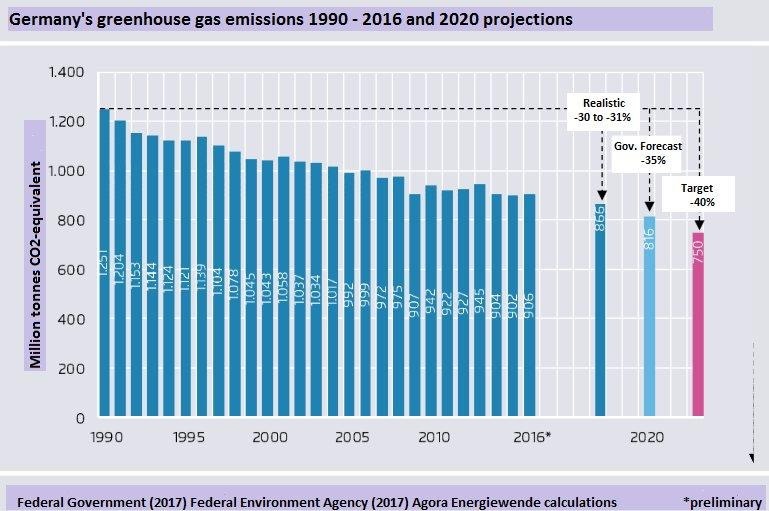

The result is that Germany's greenhouse gas emissions actually increased in 2016, and are expected to grow even more in 2017.

This begs the question: how will Germany kick its coal habit?

Coal on the agenda

For Germany to meet its climate goal of becoming close to carbon-neutral by 2050, it needs to stop burning coal and leave it in the ground today. Germany is also on course to spectacularly miss its 2020 climate target, according to a study by the think-tank Agora Energiewende, which says the government’s estimates are too rosy. The country also risks jeopardising its international reputation as a leader in the global fight against climate change.

There is an urgent need for action but a fierce political debate is raging over how the coal phase-out process should unfold.

To get back on track with climate targets, Agora is calling for Germany to adopt an emergency "Climate Protection 2020" programme as soon as possible after the federal elections this month.

And some utilities are already shutting down old coal plants for economic reasons. The power company STEAG, for instance, will decommission five coal-fired units because of low wholesale electricity prices. Other companies are hoping that a political agreement on phasing-out coal power will be sweetened by financial benefits for those shutting down plants.

An EU agreement on stricter pollution standards for existing power plants starting in 2021 will also factor into plans for a phase-out. Notably, the German government voted against these stricter standards.

Gerard Wynn from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) estimates that Germany has many gigawatts of coal and lignite generating capacity above the new limits. Owners are facing multiple headwinds: competition with renewables, sluggish power demand growth, and carbon emissions targets. Owners will have to decide whether to retrofit or close their plants. “Utilities may use this opportunity to close or sell certain coal plants before the new standard is implemented in 2021,” he said.

Germany’s current government coalition has avoided specific discussion of a coal phase-out. But there are signs that preparations for one are underway.

Under a new programme by the Ministry of Economics, lignite mining areas can apply for federal funds to develop model ideas for economic transition in mining regions. The four-million-euro programme starts in 2017.

For the Paris Agreement, deputy economy minister Rainer Baake says Germany will have to shut half its existing coal power capacity by 2030.

Most importantly, the government’s Climate Action Plan includes a commission to address the challenges of a coal phase-out. In 2018, this commission for “growth, structural change and regional development” will develop suggestions to support coal regions in the transition.

This could provide the next government coalition with a foundation for implementing the coal phase-out. But what might that coalition look like?

Parties and coalitions

Clean Energy Wire provide a great summary of where the parties stand on energy and climate issues here. Depending on the result of the election, three scenarios for a coal phase-out appear likely:

Limited action – Another “grand coalition” of Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and Social Democratic Party (SPD) would likely continue the Energiewende with little ambition. The parties support decarbonisation in general but are weak on the details. Both parties highlight the need to provide economic support for coal mining regions, such as workforce retraining. But the state governments of these regions are opposed to a coal phase-out in order to drive up the price for an agreement. The state premier of Saxony-Anhalt, Rainer Haseloff (CDU), says lignite will remain indispensable in Germany until 2050. The Social Democrats are traditionally close to the coal unions and utilities and avoid talking about a coal phase-out, highlighting the need to keep industrial traditions in coal regions by creating new jobs.

Putting the brakes on – The traditional centre-right coalition of CDU/CSU and Free Democratic Party (FDP) would likely slow down renewables growth and delay plans for a coal phase-out. Following the recent win in state elections in North Rhine-Westphalia by the CDU and FDP, the parties are already looking to limit investments in new wind power. The coalition in the state also announced it will overturn NRW’s climate protection law and oppose a coal phase-out at the national level.

Higher ambition – A coalition of CDU/CSU, FDP and the Green Party would be the most fascinating because the parties have contradictory positions on the Energiewende. FDP leader Christian Lindner sees “high hurdles in energy policy” for a coalition with the Green Party. The Greens underscore their demand for a coal exit by 2030, and for shutting down the 20 dirtiest coal-fired power plants immediately. Of course, the Greens wouldn’t be able to force all of their demands, but in comparison to the other likely coalition options, this one seems to be the most likely to push forward with a coal phase-out.

Coal power protesters march in front of a power station owned by utility RWE (Image: Ende Gelände/Flickr)

After the elections

Three out of four Germans expect the next government to issue a coal phase-out plan. In a survey commissioned by Friends of the Earth Germany (BUND), 59% of respondents said that German coal-fired power plants should be decommissioned “soon”.

Chancellor Angela Merkel, who is a strong favourite for a fourth term, said her government is still committed to reaching the country’s 2020 climate target, despite the recent increase in emissions. Asked if she thinks the government will succeed, Merkel said: “I’m working on making it happen, yes.”

Internationally, Merkel gets a lot of credit for her constructive role in securing the Paris Agreement. She also strongly defended the Paris Agreement against the US government as president of the G20 in 2017. But so far, she has done little at home to deserve her climate reputation. “There’s a growing gap between successful climate diplomacy on the international stage and a virtual standstill on domestic climate policy,” says Christoph Bals of the non-governmental organisation Germanwatch.

So it remains to be seen when Germany will go coal-free, although most predictions range from 2030 to 2050. Clearly, the election will have an impact on the way forward, with the Green Party being the most ambitious in a potential coalition. But the government will continue to respond to pressure from stakeholders.

That’s why Ende Gelände is calling for more mass actions of civil disobedience.

Arne Jungjohann is an energy policy analyst and Green Party member.