The announcement of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 has given rise to a lot of discussion about “transboundary connectivity”, the building of pipelines, roads, railways and electricity connections.

One of the most ambitious embodiments of this idea is the Global Energy Interconnection (GEI) initiative, a borderless network that would enable electricity to flow freely between countries. It was put forward by Liu Zhenya, chairman of the State Grid Corporation of China (the world’s second largest company after Walmart) in 2015.

To move the initiative forward, the State Grid launched the Global Energy Interconnection Development and Cooperation Organisation (GEIDCO). This Beijing-based organisation has since been joined by dozens of equipment manufacturers, energy corporations, business associations and civil society groups.

GEIDCO claim that the grid could help the United Nations (UN) implement its “Sustainable Energy for All” agenda, and help meet the Paris Agreement target to expand access to low-carbon electricity around the world. Even the UN secretary general praised it as a means of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

Not the first proposal

The idea of a transnational grid has been around for a while. As Walt Patterson wrote for chinadialogue in 2016, similar proposals date back at least to the 1970s when an initiative known as the Global Energy Network Institute pushed for an electricity grid spanning the entire planet.

A less ambitious proposal was announced in 2003 by Desertec. It envisaged huge investment in North African solar generation connected by subsea cables across the Mediterranean and into the European grid.

But those early dreams never made it off the drawing board because of multiple political, cultural and economic obstacles.

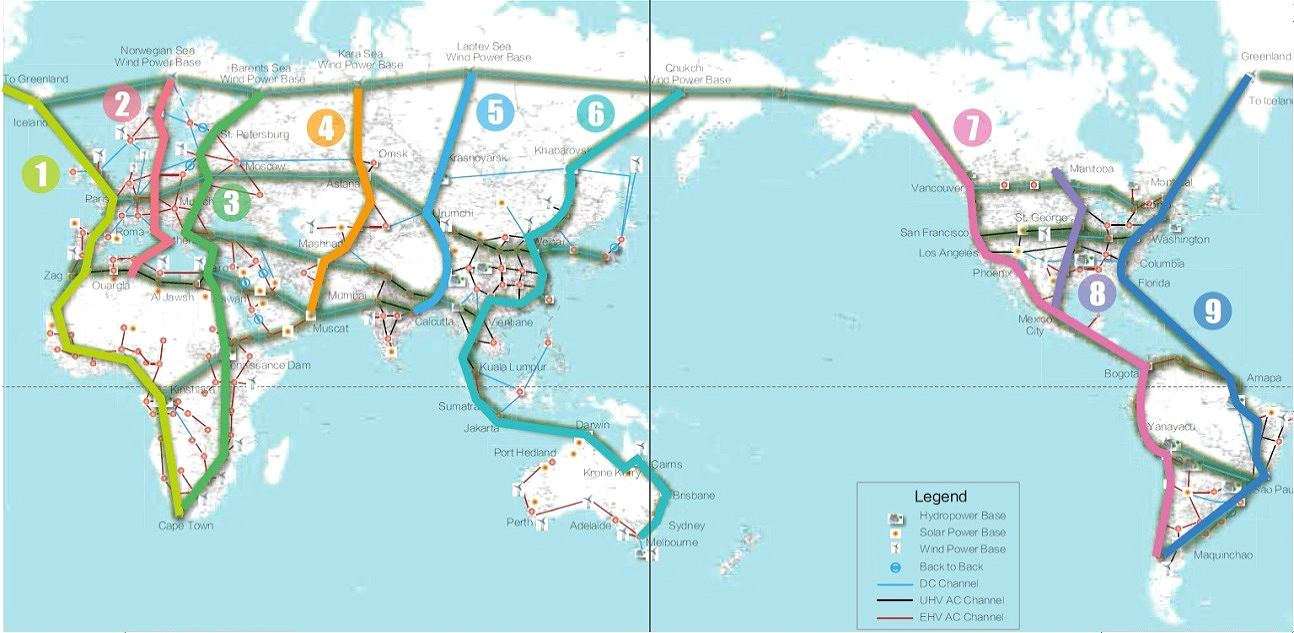

China’s own technocratic vision for a global supergrid envisages high-voltage interconnection crossing continents and the ocean. By 2050 it promises 720 gigawatts of transboundary power flow, at an estimated cost of US$38 trillion, including US$11 trillion in power grid investment.

By 2050 it promises 720 gigawatts of transboundary power flow at an estimated cost of US$38 trillion

The power would flow from large “clean energy bases” with showcase mega-projects, including; a massive 50 gigawatts of Siberian hydropower from the Lena and Amur rivers basins; a 100-gigawatt “wind power circle” in the heart of the Arctic; and African dams to harness the flow of the Nile, Congo and Zambezi rivers. To top it off, solar farms would cover 5% of the Sahara Desert.

According to Liu Zhenya, the GEI is the only means to ensure the deployment of renewable energy on a global scale.

Map of GEI land and sea channels by 2070 (Source: Global Energy Interconnection Backbone Grid Research, GEIDCO 2018)

Map of GEI land and sea channels by 2070 (Source: Global Energy Interconnection Backbone Grid Research, GEIDCO 2018)

Smarter supply

In some cases, electricity interconnection projects can reduce the need to build new power generation thereby benefiting the environment.

A good example is the Egiin Gol hydropower project in Mongolia that’s located in the Lake Baikal Basin, which is shared by Russia and Mongolia. Environmental NGOs, scientists, the World Heritage Committee, and even Russia’s President Putin, insist that hydropower stations planned on the Selenge River and its tributaries that feed Lake Baikal threaten this World Heritage site. Responding to pressure, the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) froze a US$1 billion loan for the proposed project two years ago.

However, the hydropower plant could help Mongolia respond to its intermittency problem, according to the government. The country has new wind and solar projects licensed for construction but says it needs other, more constant forms of generation for when these sources fail.

Russia’s solution has been to propose a draft agreement to guarantee a transparent, equitable and secure electricity trade across the border. It even dropped the price for exported electricity during Mongolia’s daily peak demand to discourage investment in new hydropower.

The agreement also calls for “consideration of environmental impacts of energy projects planned in the region” and invites “third countries” to implement energy supply projects. Unsurprisingly, the third country referred to is China.

China is in a position to use its advanced electricity transmission technologies to build a better transboundary grid along the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor. In this case, such a grid would offer an alternative to building additional harmful power generation.

An opportunity for China

Liu Zhenya, GEIDCO chairman, has said that the supergrid is “a road towards transformation, green development, prosperity, harmony and happiness.” But for all this lofty rhetoric, GEI is principally a means for China to spread its industrial capacity globally, also a key objective of the Belt and Road initiative.

China already possesses the advanced technologies in high-voltage transmission, hydro-engineering, and solar and wind power to deliver on proposed projects and can introduce its technology on all continents.

Chinese companies have announced investments of US$102 billion in building or acquiring power transmission infrastructure across 83 projects in Latin America, Africa, Europe and beyond over the past five years, according to the Financial Times. China’s State Grid alone has spent at least US$30 billion in Brazil, Australia, Italy, Greece, the Philippines, Hong Kong and Portugal buying grids and utility companies.

Unfortunately, none of the detailed documents published by GEIDCO acknowledge the potential negative environmental impacts of its intended energy system or ways to prevent them.

Greenwashing

The planned Evenkiyskaya dam in Siberia’s Yenissey River Basin; the Grand Inga dam in Congo; and the Belo-Monte dam in Brazil (which included a high-voltage 4,500 kilometre transmission line built by State Grid) are just three examples of how supergrids can enable environmentally and socially damaging “clean energy” projects, which block major rivers essential to indigenous peoples’ livelihoods.

Giant transmission lines also have major impacts. They fragment pristine ecosystems and displace local communities. GEI envisions the construction and maintenance of 175,000 kilometres of “backbone” supergrids by 2050, at a cost of US$4 million per kilometre. This could prove to be a disastrous waste of money.

High-voltage grids designed to carry clean energy are often dominated by coal power instead. State Grid is also planning to link to large coal-thermal energy bases abroad such as the 4-gigawatt Erkovetskaya plant in Russia and 8-gigawatt Shivee-Ovoo in Mongolia.

However, China’s domestic supergrids have been highly-subsidised and are struggling to inject electricity from western regions into east-coast provinces, where local generation is preferred. The experience is a cautionary tale for the prospects of unimpeded “transprovincial” energy trading, let alone transnational trade.

Supergrid or distributed renewables?

Multilateral development banks seem predisposed to ideas such as GEI given their tendency to invest in mega-projects and promote transboundary infrastructure and trade.

One example is the CASA-1000 Project initiated by the World Bank a decade ago, which would transmit hydropower from Tajikistan and the Kyrgyz Republic to consumers in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The project is still struggling to hire contractors to erect transmission lines. Despite being unfinished, the transmission project is still used to justify the construction of new hydropower in Central Asia that could link to it.

A more recent example of this predisposition to transboundary projects among development banks is the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which promotes “connectivity” as one of its key principles.

At public consultations on the AIIB’s Energy Strategy, NGOs argued that financing high-voltage transmission lines across national borders and regions promotes continued investment in large, centralised energy systems. They suggested that investment in small-scale renewables combined with smart grid management would be more appropriate in many cases.

The AIIB has acknowledged the “potential social impacts and risks of ecosystem fragmentation” from new electricity generation projects but does not consider the risks associated with connecting projects.

This risk management approach, which fails to recognise the risks of generation projects and connectivity together, is practised by most international finance institutions. It means that support for highly destructive energy systems continues despite commitments to high environmental and social standards.

NGOs trying to advocate for sustainability in energy projects also tend to be compartmentalised. Many address the impacts from coal, some look at hydro, and few monitor the potential impacts on biodiversity and local community livelihoods from new wind and solar, which together made up almost 60% of net capacity additions in 2017 worldwide.

But practically no one monitors the environmental consequences of supergrids as a whole. It is time for all GEI stakeholders and critics to suggest a framework for assessing the social, economic, geopolitical and environmental sustainability of supergrids in the context of alternatives available for global energy system development.

Only then might GEI’s goal of “green development, prosperity, harmony and happiness” be achieved.