In the past year, Egypt signed contracts to build the world’s largest coal-fired power plant and broke ground on the world’s largest solar farm – both with the help of Chinese banks and contractors.

These mega projects highlight a growing gap between China’s vision of South-South climate cooperation, which prioritises clean energy projects, and its actual investments across the African continent, which still include coal and hydropower projects that pose serious environmental risks.

Setting the energy and climate roadmap

Leaders from 53 African nations are gathered in Beijing from September 3-4 for the triennial Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Established in 2000, FOCAC is an arena for China and Africa to deepen their political and economic ties, which are increasingly important given that China has become Africa’s third largest investor.

At past summits, Chinese presidents committed major loans to African nations – US$5 billion in 2006, US$10 billion in 2009, US$20 billion in 2012, tripling to US$60 billion in more broadly defined “investment” in 2015.

A portion of these loans has gone toward energy projects. Boston University data shows that energy lending to Africa by the Export-Import Bank of China, and China Development Bank, which are the main financiers of the country’s overseas investment, went primarily to hydropower, oil, and coal from 2000-2016.

Although China is still funding fossil fuel projects and hydropower (the latter is low-carbon compared to natural gas or coal-fired power but it produces more greenhouse gases than wind and solar), it has signalled at previous FOCAC summits the need to mitigate climate change in its investment decisions.

At the 2009 FOCAC, Premier Wen Jiabao proposed an initiative to build 100 clean-energy projects in Africa. China’s US$3.1 billion South-South Climate Cooperation Fund was referenced in the 2015 FOCAC action plan as a way to bolster climate action in Africa.

Nonetheless, some experts think that China is not taking strong enough action. In a recent podcast interview by The China Africa Project, experts anticipated green issues would be side-lined at this year’s conference. Civil society leaders in Africa have called for change: Makoma Lekalakala, director of the non-governmental organisation Earthlife Africa in Johannesburg, said “We hope that at this year’s FOCAC there will be a greater focus on Chinese investment in clean energy in Africa.”

Fossil finance

China is in a position to shape the direction of Africa’s energy development. According to a report by Oil Change International, China was the largest provider of public finance for energy development in Africa from 2014 to 2016. Most of this went to upstream oil and gas (72%), followed by coal-fired power and large hydropower projects.

Source: Oil Change International's Shift the Subsidies Database

Around a third of African coal-fired power plants built in the decade up to 2016 were constructed by Chinese contractors, the majority with Chinese funding, according to a 2016 report by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Coalswarm, a Wiki encyclopaedia that tracks coal projects globally, shows that China has been involved in the finance or construction of 15,700 megawatts of coal capacity in Africa – around 10% of the continent’s total power capacity (168,000 megawatts in 2016).

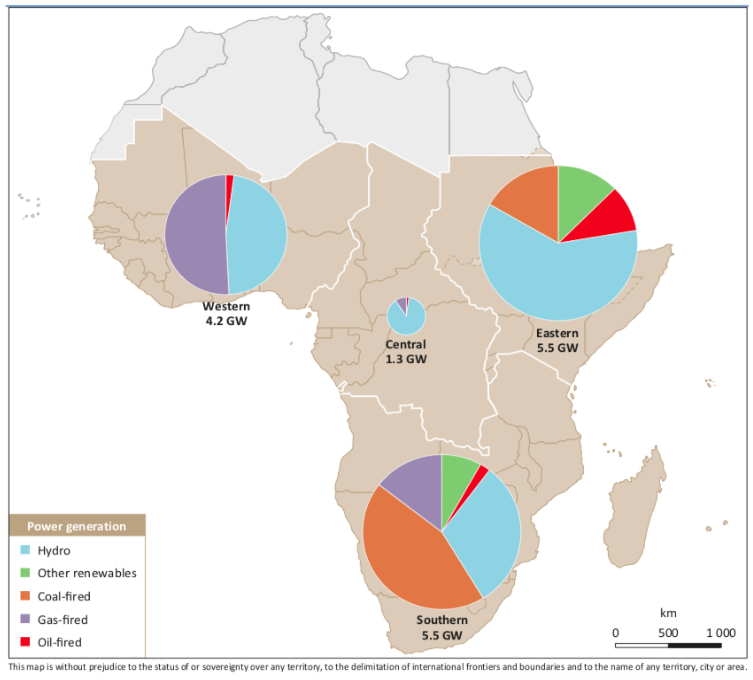

These coal power projects have typically been located in countries with domestic coal resources: almost three-quarters of Chinese-built coal-fired capacity is in Southern Africa where coal reserves are available, the IEA report says.

Distribution of Chinese projects in power capacity, by sub-region, 2010-2020

Source: IEA

Source: IEA

However, new projects have been proposed in countries where coal is not a mainstay of power generation, including Kenya, Ghana, and Egypt. The latter’s 6,600-megawatt Hamarawein mega project, which will be built by Chinese contractors, represents a further backslide toward coal following Egypt’s reversal on a ban on imports for coal power in 2015.

Nascent clean energy development

China’s involvement in Africa’s renewable energy sector (excluding hydropower) has been limited. According to IEA, from 2006-2016 only 7% of Chinese-built power generation in Sub-Saharan Africa were non-hydropower renewable plants. These include solar projects in Comoros, Kenya, DRC, and Senegal, and wind projects in Djibouti and Kenya.

However, a new wave of projects is on the horizon. A 2018 report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) cited an additional 200-megawatt solar farm to be built by PowerChina in Bui, Ghana; and the 244.5 megawatt De Aar wind farm being built by China’s Longyuan Power Group Corporation near Cape Town, South Africa; along with the Benban solar farm in Egypt.

Chinese solar and wind companies are also serving as equipment manufacturers and suppliers. In 2014, Jinko Solar built a solar PV factory in South Africa, and GCL just announced it is following suit in Egypt, increasing the companies’ access to the African market.

Shifting to green

The South-South Climate Cooperation Fund, launched in 2015, established a vision of China as an emissary of clean energy in other developing countries. One of the fund’s goals is to support 100 climate mitigation and adaptation projects.

The fund has had a slow start. However, Wang Binbin, a researcher at Peking University, argues it is gathering pace and will be helped by the creation in April of China’s first aid agency, which will assume responsibility for the fund.

Directing both climate aid and loans toward renewable energy would have major implications for Africa’s energy development. For instance, Kenya aims to be a clean energy hub by harnessing its rich renewable energy resources, but it is also planning to build its first coal-fired power plant with the help of Chinese financing. A change in China’s investment priorities could alter Kenya’s calculus about coal as other international lenders are increasingly unwilling to support such projects.

Egypt’s Benban solar farm, which is part-financed by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank – China’s flagship multilateral bank, could help drive a shift towards renewable projects, although the bank has been criticised for not sufficiently delivering on its motto to be “green, lean, and clean.”

The significant stock of fossil energy projects China has built in Africa means that it will take much more than a few high-level pledges and pilot projects. With climate change visibly impacting Africa from Cape Town’s severe drought to desertification in Mali, FOCAC presents an opportunity for leaders to align energy development with the reality of climate change.