China’s shale gas industry has been shaken by controversy after three earthquakes in Sichuan province.

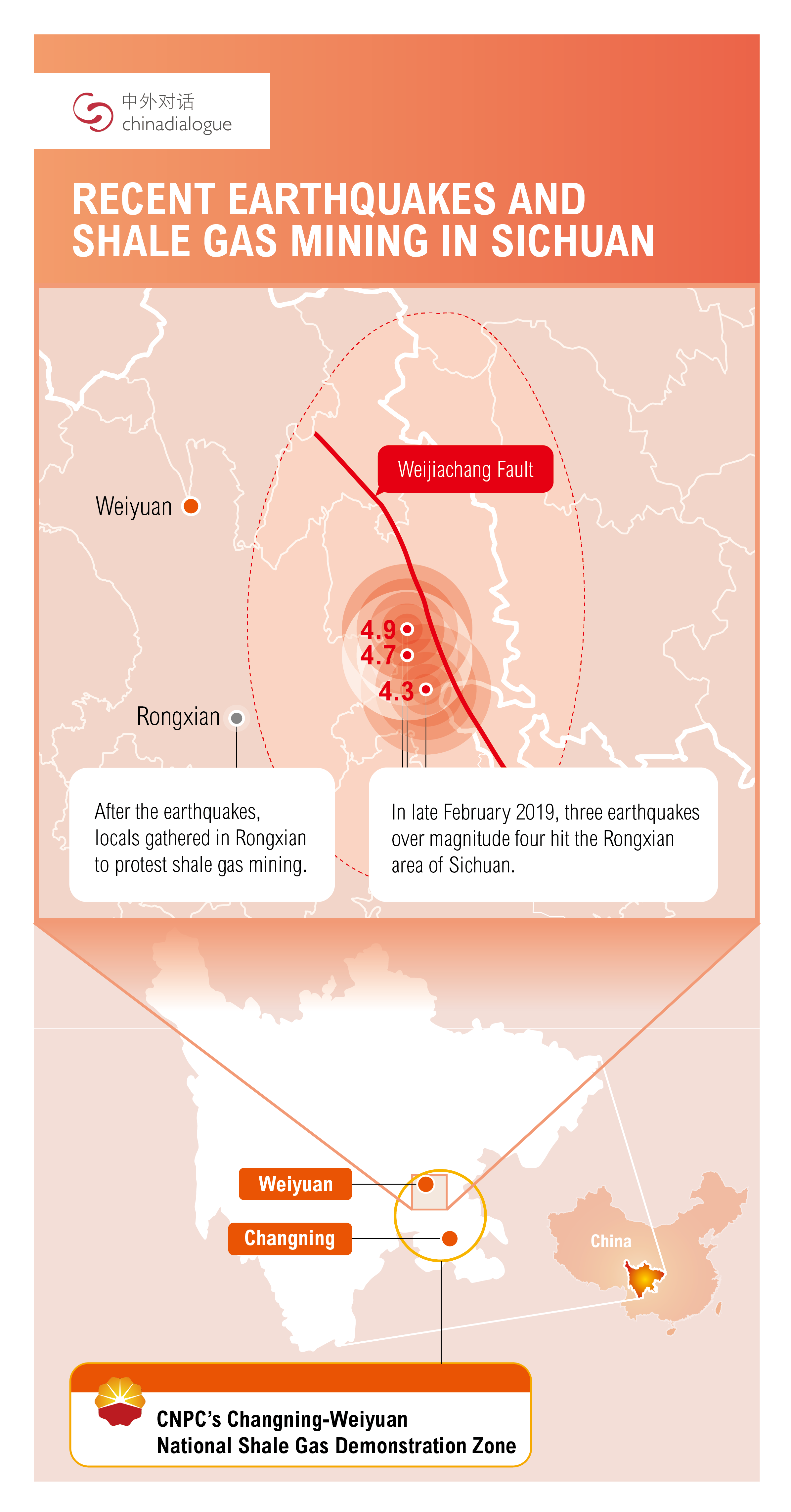

The earthquakes, all with a magnitude of over four, hit Rongxian near the city of Zigong on the 24th and 25th of February. They killed two people, injured 12 and damaged numerous buildings. Locals suspect shale gas extraction was to blame, and according to the local government, about 3,000 people gathered in Rongxian to protest the practice shortly after the earthquakes hit.

On the 25th the local government instructed shale gas firms to temporarily halt operations for the sake of what they called “earthquake safety”. There has been no word as yet on when extraction will start again.

Shale gas mining has proved highly controversial worldwide due to its potential safety risks and environmental impacts. Although the public response in China has not been equivalent, February’s protests are a sign of how high feelings run. Nevertheless, experts say this is unlikely to reduce the ambitions of government and businesses.

Cleaner energy

Market demand is behind China’s increased efforts to find and extract shale gas.

Shale gas is referred to as an unconventional natural gas, but it is effectively the same fuel. A cleaner and lower-carbon option than coal, natural gas is viewed as a transitional source of energy as the mix of energy changes to tackle air pollution and climate change. As a result, it has seen rocketing demand. In 2017 demand for natural gas outstripped supply by 4.8 billion cubic metres in northern China (where need is higher due to heating demand) and 11.3 billion cubic metres nationwide.

Na Min, chief information officer with BSC Energy, said: “Shortages naturally mean more capital flowing into the shale gas sector, encouraging upstream companies to prospect and increase output.” According to the firm’s calculations, China’s demand for natural gas will continue to grow in 2020.

Strong growth in demand for natural gas has also caused reliance on imported gas to escalate, with policymakers becoming concerned about energy security. In September 2018 the State Council published its first document promoting development of the natural gas industry, instructing domestic oil and gas firms to increase prospecting and development funding to boost output and reserves.

Li Rong, chief public sector researcher with Cinda Securities, said there is little chance of natural gas discoveries being made in China in the near term, so any breakthroughs will have to come from unconventional sources: shale gas, tight gas and coalbed methane. “Future increases in domestic gas production will mainly come from unconventional sources, such as shale gas,” she said.

A growth bottleneck

But China’s shale gas ambitions predate the recent leap in demand for natural gas.

Shale gas extraction started in the United States, where technological improvements in the early 2000s led to rapid expansion, making the country much less reliant on energy imports. China is now looking to the US and hoping to replicate that success. According to estimates from the US Energy Information Administration, China has more shale gas reserves than any other nation – using current technology, its recoverable reserves are 68% larger than those of the US. China hopes this will provide energy self-sufficiency.

China’s Ministry of Land and Resources started investigating shale gas resources in 2004 and the first exploratory well was drilled in 2009.

2012 saw an ambitious five-year plan for shale gas development, with a production target of 6.5 billion cubic metres per year for 2015, and a subsidy of 0.4 yuan (US$0.06) per cubic metre for shale gas firms between 2012 and 2015. But by 2015 production stood at only 4.5 billion cubic metres per year, with only the two state-owned oil and gas giants, CNPC and Sinopec, running commercial operations.

BSC Energy’s Na Min says that further increases in output are being held back by bottlenecks in the prospecting and commercialisation process.

The Sichuan basin, where the recent earthquakes occurred, is one of China’s three richest natural gas basins and currently the most suitable for drilling. But reserves are deeper compared with the US, and the geology is more complex. That means technology used at one well may not be useful at another, even when its nearby, making prospecting and extraction more challenging and costs harder to control. The area is also densely populated, and intensive drilling could ferment public discontent.

Despite this, the current five-year plan for shale gas has raised production targets again: “Assuming policy support is in place and market conditions are favourable, strive for annual shale gas production of 30 billion cubic metres by 2020.” This is lower than a pre-2015 target for 2020 of 60-100 billion cubic metres, but ongoing subsidies and tax breaks show that China still has high hopes for shale gas.

Earthquake worries

One of the main reasons members of the public oppose shale gas extraction is the link with earthquakes. This is especially so in Sichuan, where memories of the 2008 earthquake that killed over 69,000 people are still raw.

The gas is found in layers of shale rock, and hydraulic fracturing – the high-pressure pumping of water, sand and chemicals into the rock formation – is necessary to extract it, by enlarging cracks and allowing the gas to escape. This creates a lot of contaminated wastewater, which is often dealt with by injecting it into deep disposal wells.

Although the whole process is controversial, for both safety and environmental reasons, it is the injection of this wastewater that is thought to trigger earthquakes. In 2013 the US Geological Survey published research in Science saying “several of the largest earthquakes in the U.S. midcontinent in 2011 and 2012 may have been triggered by nearby disposal wells”.

The epicentres of February’s earthquakes were all about eight kilometres from Rongxian, right in the middle of CNPC’s Changning-Weiyuan National Shale Gas Demonstration Zone.

Despite this, some experts say it is hard to draw a direct link between the earthquakes and shale gas extraction in the region. Zhang Jianqiang, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Chengdu Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, explained that the epicentres lay five kilometres beneath the surface, some distance from the deepest fracking at about 3.4 kilometres. Zhang claimed that a causal relation could therefore be eliminated, although further research would be necessary. He made no reference to wastewater disposal wells.

According to Tian Bingwei, associate professor at the Sichuan University – Hong Kong Polytechnic University Institute for Disaster Management, this area is prone to seismic activity. There have been five earthquakes of magnitude four or above within a 50-kilometre radius of February’s epicentres since monitoring began in 1970, a relatively high number.

But there are also other concerns about fracking, such as the huge quantities of water used. According to research from the World Resources Institute, 61% of China’s shale gas reserves are in areas under high levels of water stress. But WRI researcher Luo Tianyi argued that Sichuan lies in the Yangtze River basin so has more water available than many other areas. As such, it shouldn’t suffer increased water stress, but there may be localised competition for water in the short-term, he said.

Unshakeable ambition

On 4 March during the Two Sessions, China’s biggest annual political meetings, CNPC chairman and delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Wang Yilin said in an interview that his corporation plans to produce 12 billion cubic metres of shale gas annually by 2020, and to double that to 24 billion cubic metres by 2025. This was only a week after the earthquake protests in Rongxian.

Sichuan is a focus for that expansion. In 2018 CNPC drilled 330 new operational wells in the Sichuan Basin – nearly 60% more than the total number of wells the company had in production by the end of 2017 (about 210).

Experts interviewed by chinadialogue generally agreed that the controversy over the earthquakes will not reduce the market and energy security ambitions of the shale gas sector and the government. But they said it will be necessary to address the discontent of residents and avoid putting the public at risk.

Li Rong of Cinda Securities said there should be a full scientific review of the risks of shale gas mining to ensure the safety of locals and their homes. She also suggested that during mining or well drilling, seismologists should be employed to monitor any links with earthquakes, and during initial site selection, seismic risks should be an essential part of environmental impact assessments.

Commenting on the huge quantities of water used, the WRI’s Luo Tianyi said that mining firms need to plan when and how they mine in line with seasonal water availability, local hydrology, and local demand for water.