One hour west of Cambodia’s capital an array of iridescent panels stretches between palm trees, glistening through dust clouds from a neighbouring highway. A year ago it was a barren expanse of chalky soil. Now it’s Cambodia’s largest solar farm.

The joint Cambodian-Chinese project, which came online in August, is only Cambodia’s second utility-scale solar project. But the government has approved more than four major solar farms to be built across the country.

For a nation that has relied on massive dams, fuel oil, and more recently, coal power for electricity, the solar surge is a significant step toward a lower-carbon electricity grid. However, Cambodia has also signed off on more fossil fuel power plants. As electricity demand in the country and across Southeast Asia continues to climb, whether solar can displace fossil-fuel-generated power will greatly influence the region’s air pollution and carbon emissions.

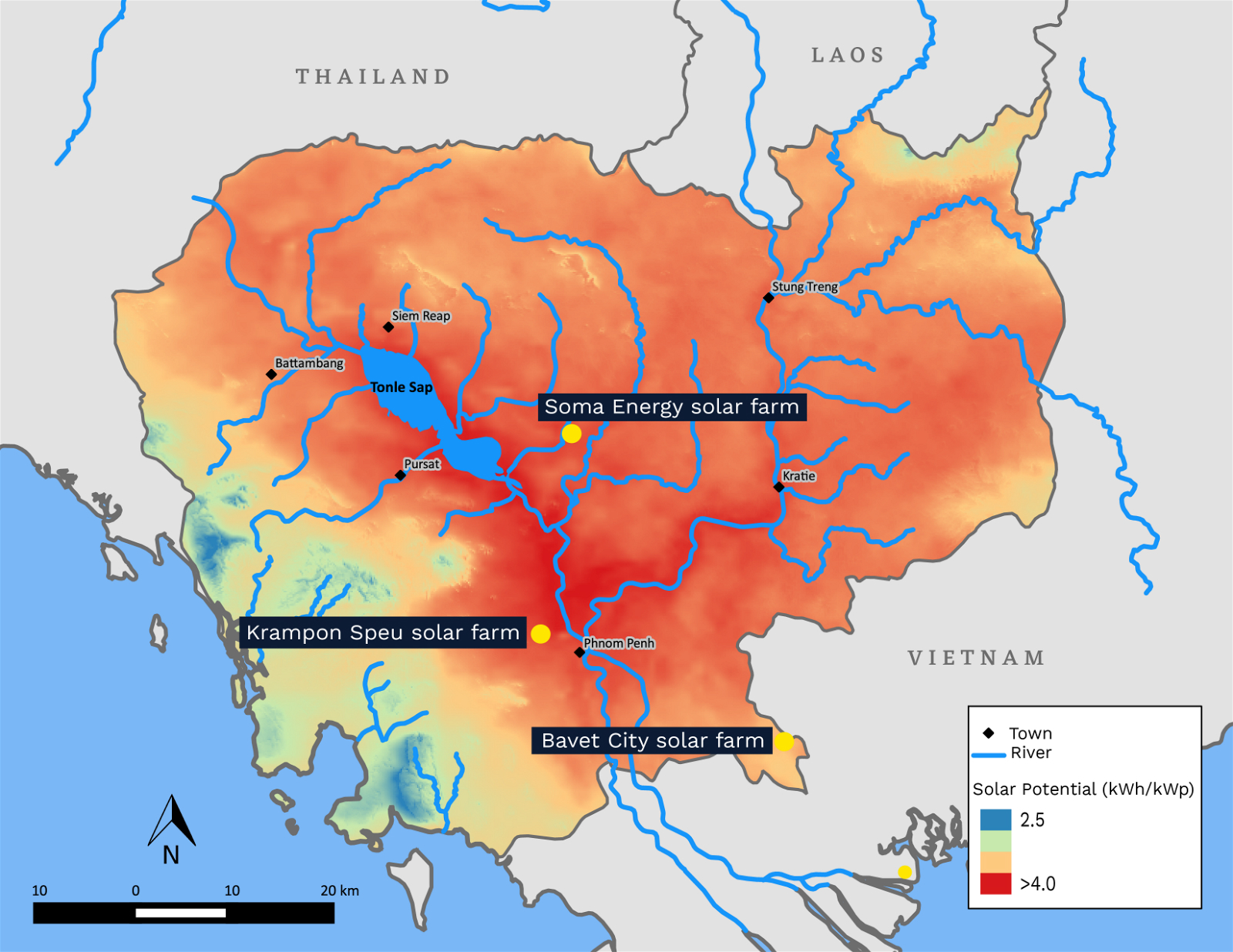

Cambodia’s solar potential

(Image: adapted from Stimson Center)

With its sunny climate, Cambodia has strong solar-development potential: an estimated minimum of 8,000 megawatts of capacity. But as recently as 2016 the Cambodian government was sceptical of solar. Policymakers expressed concerns that it was too expensive and unreliable, and the government did not include any renewable energy projects or targets in its national energy plan.

“Five years ago, I think it still was reasonably correct for policymakers to say that they did not see a way for solar to compete with alternatives that were locally available,” said Courtney Weatherby, a researcher at the Stimson Center who focuses on power planning in the region. But since then the country has rapidly changed course, she said.

Over the past decade, Cambodia’s electricity usage shot up – averaging a 20% annual increase in demand since 2010. Power supplies were already having trouble keeping up, but then a lengthy drought struck earlier this year, crippling the country’s dams, which have historically provided the bulk of its electricity.

In response, the government commissioned the four new solar farms, as well as a new diesel power station and a dam. Cambodia now plans to generate 20% of its power from solar within the next few years, up from just 1% in 2018.

The fact solar farms can be constructed in months makes them an appealing choice to address the energy shortage; dams and fossil fuel plants typically take much longer.

Falling costs have also helped boost solar. In many countries across the region, new solar plants are now less expensive than coal plants.

Developers from more mature solar markets in the region including Thailand and Vietnam have sought out opportunities to build and invest in Cambodia’s burgeoning solar market, said Weatherby.

Solar milestones

The 80-megawatt solar farm that came online this summer in Kampon Speu province is the most significant project yet in Cambodia’s turn toward solar. Before it broke ground, Cambodia’s only utility-scale solar farm was a 10-megawatt pilot project funded by the Asian Development Bank.

The Kampon Speu project has shown that solar is commercially viable in the country – selling power to the utility at a rate competitive with other power sources.

One factor driving costs down is the price of panels. SchneiTec, the project’s developer, is a joint Chinese-Cambodian venture and JinkoSolar, a China-based company that is the largest solar panel manufacturer in the world, supplied the site’s panels. Last year, China had a glut of solar panels, which brought panel prices down globally.

An 80-megawatt solar farm developed by SchneiTec in Cambodia’s Kampon Speu province (Image: Lili Pike/China Dialogue)

Arif Ibrahim, a sales manager at JinkoSolar who covers the Cambodia market, said the company is actively looking for new opportunities there. “We have seen a lot of upward movement in the Cambodian solar industry in 2019 compared to previous years.”

The growing strength of Cambodia’s solar market can be seen in a recent milestone. The Asian Development Bank has provided a loan for a 100-megawatt solar park. And an auction for companies to develop the first 60 megawatts of the park saw the lowest solar auction price in Southeast Asia – 3.88 cents per kilowatt-hour. The price was partly driven down by development bank financing and land and transmission costs being borne by the utility, but Ibrahim said it was still significant. “It shows that solar projects in Southeast Asia are becoming more and more competitive.”

Will solar replace fossil fuels?

Although solar has surged this year, its future remains uncertain. Solar resources and land are available, but everything depends on the government’s plans, said Say Sotheara, the general manager of SchneiTec.

“The bright future for solar power in Cambodia depends on the growing support by the government in terms of policies and regulations,” said Ibrahim.

With the looming threat of another crippling dry season, the government has unveiled plans to generate more electricity from fossil fuels along with solar. The government recently agreed to purchase 2,400 megawatts of coal power from across the border in Laos. These projects are part of a broader problematic trend across the region: Southeast Asia has to phase out coal almost entirely by 2030 to stay within the Paris Agreement goals of keeping global warming well within 2C, but dozens of new coal plants are planned or under construction.

However, for a country that had no utility-scale solar on the grid until recent years and a government that was sceptical of renewables, Cambodia is making strides. It has yet to formalise policies to incentivise solar development, but the government is increasingly backing solar. “I do think it is a notable shift that you have got high-level government officials from the ministry of mines and energy and from EDC, the utility company, saying that they want to see this level of solar investment in the country,” said Weatherby. “That itself is a big policy change.”

With reporting assistance from Sokhorng Cheng