Record-setting levels of smog this week shut down Harbin, a city of 11 million people in northeast China. Officials blamed increased coal consumption during the first days of winter heating, underscoring the urgency of the China State Council’s recently announced initiative to address persistent smog in major cities.

But while the Air Pollution Control Action Plan has ambitious goals—cutting air particulates and coal consumption—it may create unintended problems for the country’s water supply.

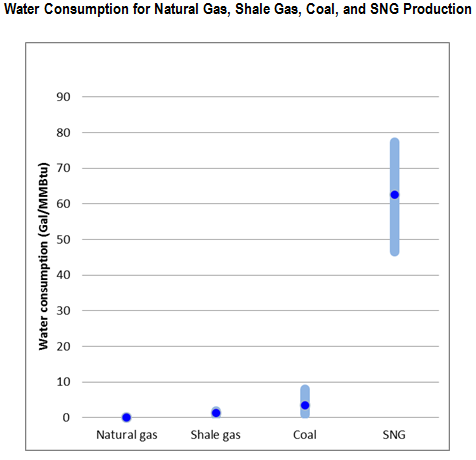

The Plan aims to reduce particulate matter in the North China Plain by 25% and reduce coal’s share of the national energy mix to 65% by 2017. One of the plan’s key recommendations is to replace coal with cleaner natural gas, including synthetic natural gas (SNG) converted from coal. Converting coal to natural gas, however, is an extremely water-intensive process. One cubic meter of SNG requires 6 to 10 litres (1.58-2.6 gallons) of freshwater to produce. China’s attempt to control urban air pollution in the east might jeopardize its water supplies elsewhere.

The World Resources Institute (WRI) overlaid the locations of the approved SNG plants on water stress maps to assess the potential water risks. Many of these plants are located in water-stressed regions, and could exacerbate water scarcity.

China’s proposed SNG plants, most of them located in arid and semi-arid regions in Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia, will together consume (i.e. not return to the source) a total of 500 to 700 million cubic meters of freshwater annually at full operating capacity. That’s almost 20% of the region’s total industrial water use in 2011. The plants would therefore significantly exacerbate stress in areas already experiencing chronic water shortages.

More than 76% of the proposed SNG capacity will face high or extremely high baseline water stress, meaning each of the locations either competes with many other users for limited available water supplies, or has very little water available at all.

11 of the approved plants, eight from Xinjiang Province and three from Inner Mongolia, are located in catchments that do not have major reservoirs. They also face medium-to-high or high risk from seasonal variability. So, in the dry season, those plants may have to reduce production capacity or experience temporary outages due to the lack of resilience in water supply.

Beijing will also become the first Chinese city powered by SNG, receiving at least 4 billion cubic meters of the fuel annually. This production would consume more than 32 billion litres of freshwater, enough to meet 1 million Inner Mongolians’ domestic needs for an entire year.

SNG development around the city of Ordos illustrates how these water-intensive plants can disrupt regional water security. In the middle of the Mu Us Desert, Ordos’ booming coal-to-gas bases face severe competition for water between domestic and industrial users. WRI’s analysis found that Ordos’ five approved SNG plants will need approximately 140 million cubic meters of freshwater annually, which is around 10% of Ordos’ total water supply, or 40% of the region’s industrial water use as of 2011. Once these SNG plants are completed, they could further disrupt water supplies for farmers, herders, and other industries.

While SNG emits fewer particulates into the air than burning coal, it releases significantly more greenhouse gases than mainstream fossil fuels. Peer-reviewed studies in the journal Energy Policy estimate that life-cycle CO2 emissions are 36–108% higher than coal when coal-based SNG is used for cooking, heating, and power generation. Rapidly deploying SNG projects might, therefore, be a step backward for China’s low-carbon energy strategy.

China’s government will need to think carefully about whether SNG’s air pollution benefits outweigh its water and climate change costs. Water authorities should consider tightening caps on industrial water withdrawal and water-pollutant discharge or introducing stricter local environmental standards in high water-risk area.

A version of this piece was first published on the World Resources Institute website