When crews prepared to erect five wind turbines on the Brunks’ Iowa farm three years ago, Steven and his father, Ronald, watched in awe at the magnitude of the components trucked in — 50-metre blades that a person could stand inside at the base, and large sections of steel towers that would top 90 metres when assembled.

Amid the variability in crop prices, the turbines meant a steady annual income for the Brunk family and the neighbouring farmers who also entered long-term leases allowing the turbines to be built on their land. Such lease payments can net US$5,000 to US$10,000 a year per tower, an amount that typically increases by a small percentage annually.

For Iowa, the turbines on the Brunks’ land alone can produce 11.7 megawatts of clean energy in a state that is rapidly increasing its wind-generated electricity. In total, the 60 turbines that make up the Wellsburg Project — including the five on the Brunks’ property — produce 141 megawatts annually, most of which helps power a new Facebook data centre campus 60 miles away in Altoona, Iowa.

The slowly swirling blades above corn and soybean fields have become a welcome sight for Steven Brunk. “I don’t think there is a chance of my groundwater becoming flammable or an increase of earthquakes,” Brunk says. “The impact is just so much less,” than fossil fuel extraction, including hydraulic fracturing, he says.

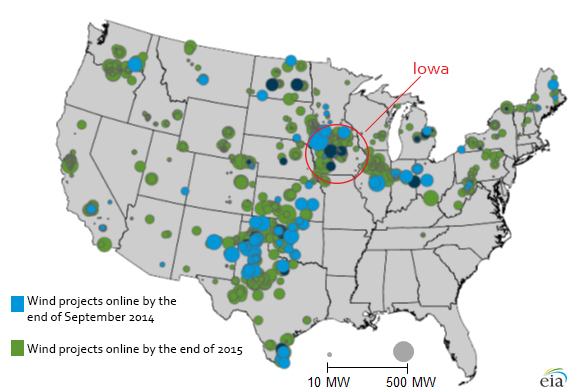

Across Iowa, wind farms such as the Wellsburg project dot the landscape, spreading across western and central regions of the state. The wind industry in Iowa employs roughly 7,000 people, supports 11 facilities that manufacture turbine-related components, and has attracted more than US$10 billion in capital investment.

The state that leads the US in both corn and pork production also has the distinction of leading the nation in percentage of its energy produced from wind, now at 31%.

In overall wind-energy capacity, Iowa is the nation’s No. 2 wind-power producer (trailing only Texas), with 6,364 megawatts of wind turbines, enough to power an estimated 1.3 million to 1.5 million homes, according to the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA).

Iowa offers a glimpse of what a thriving, apolitical renewable energy sector looks like.

Iowa — where support from the state capital came as early as the 1980s, many residents correlate the industry with green jobs, and opposition to wind turbines has not been as vocal as in some other states — offers a glimpse of what a thriving, apolitical renewable energy sector looks like. “In the national perspective, it has become left versus right,” John Boorman, vice president of the Iowa Wind Energy Association, says of renewable energy. “It has never been that here. It has always been about jobs and economic development.”

Outside the state, corporations that strongly support the push for renewable energy are taking note of all the wind farms. Facebook, Google, and Microsoft are among the companies that identified use of wind energy as one of the reasons to locate new facilities in Iowa, including the Facebook data centre in Altoona, says Debi Durham, director of the Iowa Economic Development Authority.

The rapid expansion of wind energy sites is not universally welcomed in the state. Some residents oppose the wind turbines on aesthetic grounds, while others object to the low-level noise created by the spinning blades. Still others are concerned about the turbines killing eagles and other birds. And some county planning commissions have rejected large-scale wind energy facilities on the grounds that they use up valuable farmland.

Despite this opposition, another wave of projects is now in the works in Iowa. The largest is a recently announced commitment by MidAmerican Energy Company, the Des Moines-based utility owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc., to build another 1,000 turbines that would boost the percentage of Iowa’s electricity produced by wind energy to 40%, according to state officials. The proposed US$3.6 billion project is the largest wind project MidAmerican Energy has ever undertaken, and according to the company, it’s being built without an increase in customer electricity rates or financial assistance from the state.

A recent report by AWEA and the Wind Energy Foundation says that by 2030 Iowa could meet all of its electricity needs from wind power and have enough left over to export to other states. The report spurred a roundtable discussion in January by wind energy organisations at the Des Moines Area Community College, where 70% of students in the Industry and Technology Department are enrolled in wind energy-related programmes.

That’s when then-Iowa Governor Terry Branstad — in an effort to move to a mix of industries after the farm crisis of the 1980s — signed the first state renewable energy mandate requiring a certain percentage of alternative energy generation.

According to the 2015 AWEA report, titled “A Wind Vision for New Growth in Iowa,” farmers and other rural Iowa landowners currently receive an estimated US$17.1 million annually in lease payments for hosting wind turbines on their land. The report projects that these payments could grow to US$55 million by 2030.

More than five years of planning and wind monitoring by RPM Access, a regional developer of utility-scale wind projects in Iowa, was needed before the turbines went up on the Brunks’ farmland. The elder Brunk, who shot video as workers used three cranes to hoist and assemble the different components, was proud to see the project come to fruition. “He was always into sustainability and conservation all his life,” Steven Brunk says of his father, who died in 2015 at age 80.

After construction, RMP Access sold the 60-turbine Wellsburg Project to MidAmerican. The utility operates the wind farm as part of a conglomerate of 448 turbines built from 2013 to 2015. Through an agreement between MidAmerican and Facebook, much of the electricity harnessed at the Wellsburg Project is utilised to offset carbon emissions associated with power consumption of Facebook’s data centre campus in Altoona.

State officials say the extension of the federal wind energy tax credit will help continue Iowa’s wind momentum.

Utilities small and large, from investor-held companies such as MidAmerican to rural electric cooperatives such as the Central Iowa Power Cooperative, are taking part in the state’s wind boom. “They are looking for ways to green up their energy portfolios,” says Debi Durham, director of the Iowa Economic Development Authority. “You are seeing it across the industry.”

She and others say that Congress’ extension of the federal wind energy Production Tax Credit in December 2015 will help continue Iowa’s wind-energy momentum, as will a series of proposed transmission lines that, if built, would move wind-generated electricity across the state and possibly to population centres outside Iowa. (One such proposed transmission line called “The Rock Island Clean Line,” would deliver 3,500 megawatts of wind power from northwest Iowa and the surrounding region to communities in Illinois and other states to the east.)

Companies such as Trinity Structural Towers, Inc. have bolstered wind power’s role in the state’s manufacturing sector. In 2009, the manufacturer of wind turbine towers moved into part of an old Maytag factory in Newton, Iowa left empty when the plant closed in 2007. At its Newton plant, Trinity employs about 250 people who build towers that are 79 to 94 metres tall. “The workforce has proven to be extremely capable and adept,” says Kerry Cole, president of Trinity Structural Towers, Inc.

In the next three to five years, an additional US$8 billion to US$10 billion in investment in wind farms and manufacturing is expected in Iowa, according to wind industry officials. That investment is attracting other green-minded businesses to the state. Since MidAmerican made its expansion announcement in April, Durham says several additional large, high-profile companies have contacted her agency about locating new data centres or other services there.

More land is taken by the highway that goes by my home than by the five turbines,’ says one farmer.

While the wind boom in Iowa has many supporters, from the state capitol to colleges and universities, local concerns have arisen about the aesthetics of the towers, which are getting taller. Opponents also are worried about the impact on birds and on taking farmland out of circulation.

In Grundy County, some of those concerns surfaced as plans for the Wellsburg Project took shape. The Grundy County Planning and Zoning Commission voted down the project, but that decision was overturned by the county’s Board of Supervisors. A proposal for a subsequent wind farm, Ivester Wind Farm, in Grundy County was also voted down by the zoning board; the decision was again appealed by the Board of Supervisors, and the fate of the project is uncertain. The chairman of the planning and zoning board told the The Grundy Register that protecting the fertile soil of Grundy County from non-agricultural development was his chief concern.

When it comes to energy production, there’s always a tradeoff, Brunk believes. He’s heard some residents cite aesthetics or an aversion to the hum of the turbines as the drawbacks of wind energy. But, for Brunk, at least, one concern is unfounded. “The main complaint from people was it took up farmland,” Brunk says. “Each turbine takes up less than an acre. More land is taken by the highway that goes by my home than by the five turbines.”

According to Kirk Kraft, a project manager with RPM Access, developers are trying to address another environmental concern and are working to avoid important areas for migrating eagles. The number of eagles has been on the rise in Iowa, including western Iowa. “In the last year and a half, we have spent a great deal of time and money and effort to find and steer clear of some of those sensitive areas,” Kraft says.

With the number of wind turbines increasing across the state, more farmers understand how wind energy can coexist with agriculture, says Eugene Takle, a professor of atmospheric science and agricultural meteorology at Iowa State University. Furthermore, Takle says his early research on the effect of wind turbines on crops is showing that turbulence can actually promote photosynthesis and have a beneficial effect on crops.

That’s because turbines mix up the air and increase plant motion, bringing both sunlight and some of the natural levels of carbon dioxide to lower leaves of the plants and promoting more CO2 capture by crops such as corn.

“Turbines help to push that CO2 to the plant,” Takle says. “That’s important because if the plants are taking up more carbon, weight of grain and plants will increase.”

Such potential benefits are not on the minds of most Iowans. Mainly, many farmers and other Iowans are happy to be profiting from wind power and are taking pride in the state’s role as the leader in wind power produced per capita, Takle says.

“We don’t have mountains, and don’t have the ocean,” Takle says. “We are looking for things we can be proud of, and I think there is a good feeling about generating very clean energy.”