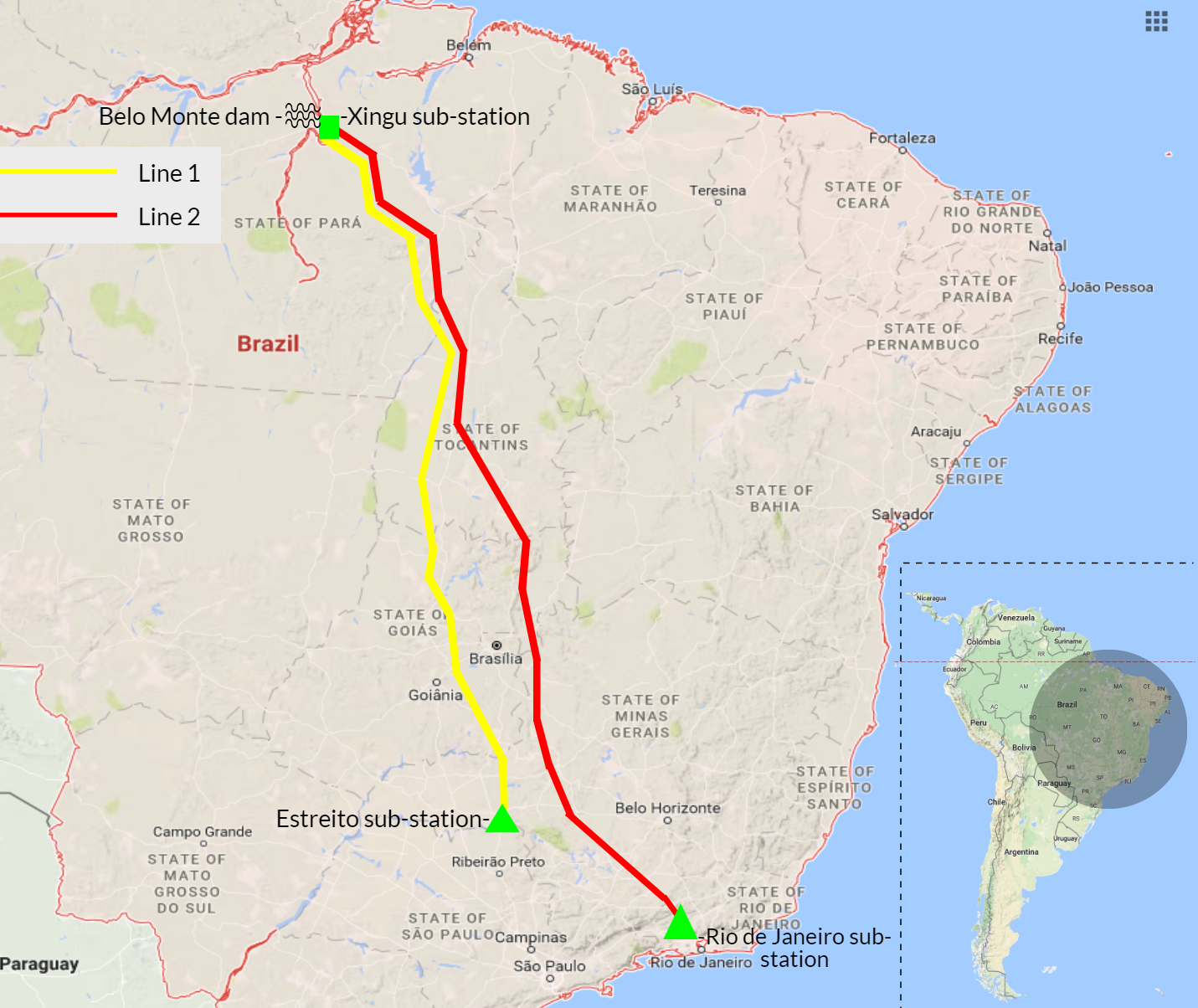

Two giant transmission lines transporting electricity from the Belo Monte hydroelectric project, in northern Brazil, to a sub-station 2,100-kilometres away will clear areas of native vegetation equivalent to 1,700 football pitches in the Amazon and Cerrado Savannah.

State Grid, China’s largest state-owned electric utility, will construct the lines. The company has become a major player in Brazil’s electricity generation and distribution sectors since arriving in the country in 2010. The first line will travel from Belo Monte, in the Amazonian state of Pará, to Ibiraci in Minas Gerais state in the power-hungry southeast of the country.

Once fully operational, Belo Monte will become the world’s third largest dam with an installed capacity of 11.2 gigawatts (GW). Despite delays and controversies over its impacts on the ecology of the Xingu River and indigenous communities, the project began generating power for commercial use earlier this year. The station is currently operating with one turbine; all 18 turbines are expected to be online by 2019.

According to the impact study for the first transmission line, 1,725 hectares of native vegetation in Brazil’s two largest biomes will be lost during its construction; with the majority (1,016 hectares) from the Cerrado Savannah. The Amazon will lose 709 hectares of native vegetation. The line also runs close to 10 conservation areas, three of which are federally protected.

The second line will be 2,500 kilometres in length and will deliver power to the city of Rio de Janeiro. Environmental studies for this second line do not mention how much vegetation will have to be cleared in order to erect the transmission towers.

Source: Milton Leal/ Diálogo Chino

However, supporters of the project claim its benefits outweigh the costs.

The power line is the first in Brazil to use Chinese-made ultra-high-voltage technology, which allows electricity to be transported over longer distances requiring fewer substations while minimising energy losses.

Newton Zerbini, environmental director at Belo Monte Transmissora da Energia (a State Grid majority-owned company), says that by using such long-distance technology supplementary generation projects are not needed, and in long-run, harmful secondary impacts are avoided.

Licensing

Brazil has complex environmental legislation, comprising over 20,000 standards. Navigating this legal framework is a difficult task for foreign companies, such as State Grid, who often see them as cumbersome and an impediment to economic development. The level of environmental regulation in Brazil has come into sharp focus since Michel Temer was confirmed as impeached former president Dilma Rousseff’s replacement on September 1.

Temer’s new cabinet includes members of powerful agribusiness lobbies, who have long argued for an end to environmental licensing, which would allow deals to be struck without the need for environmental assessments and permits. Environmentalists say that the approval of a proposed legal amendment (known as PEC 65/2012) will mean infrastructure projects could get the green light irrespective of their social or environmental impacts.

The environmental licensing process for energy projects in Brazil can cause delays that last for years. The licensing process for both Belo Monte transmission lines, however, was relatively swift.

“They obtained the preliminary licensing in six months,” says Cláudia Barros energy coordinator at the Brazilian Institute of the Environment’s (IBAMA), an energy licensing board. Barros said that one of the reasons was that the new technology removes the need for additional power generators to build along the route.

Last year, State Grid Brasil president Cai Honxgian personally visiting IBAMA to discuss their application, and potential delays which the company sees as a major risk to project. State Grid hired Concremat Ambiental to conduct the environmental impact studies.

Zerbini, who sits on joint board meetings on environmental issues with Chinese directors said they find it difficult to comprehend Brazil’s regulations. “Things are very different in their country,” he told Diálogo Chino.

According to Ênio Fonseca, president of the Environmental Forum of the Electricity Sector (FMASE), Chinese companies operating in Brazil prefer to delegate environmental compliance issues to local partners. “If they don’t have their own staff with the appropriate competencies, they have the resources to hire companies that specialise in these matters,” he said.

State Grid is an important player in Brazil and now controls over 10,000 kilometres of transmission lines having recently acquired a 23% stake in CPFL Energia, one of the country’s largest energy generation, distribution, and sales companies.

Source: Diálogo Chino

Social problems

In Uruaçu, a settlement of 40,000 people in the Goiás countryside, BMTE has built accommodation for the transmission line’s workforce just a few kilometres from the city centre. The project has created many jobs for the locals, but has also raised social concerns as three brothels have sprung up less than 20 metres from worker’s housing. Thiago César Meireles, Uruaçu’s secretary for the environment says this is normal.

“Wherever there is a large population of men, this type of trade opens. The workers live in houses with 10, sometimes 50 men. When they get paid, they want to relax,” said Meireles, who also acknowledged the project’s environmental impacts.

We contacted State Grid for this article, but the company did not answer questions submitted by e-mail. On the company’s website, the section that addresses the environmental issues of the projects is “under construction”.

The original version of this article was published on Diálogo Chino.