China’s heavily-laden banquet tables are under threat from changing tastes as the country’s growing middle class indulges in lighter, healthier foods.

Element Fresh has been serving dishes in Beijing’s Sanlitun district since 2008. The Western restaurant is a landmark in the area, attracting expats, tourists and a fair share of street photographers. But increasingly its menu is facing competition from at least four other healthy eateries nearby.

Restaurant manager Kelly He told chinadialogue that changing food habits and health concerns are attracting more Chinese people too, drawn in by the low-sugar, low-salt and low-calorie options.

Peak pork?

The nation’s health has declined in recent years and is linked to a rapid change in lifestyle including diet. A 2015 report into nutrition and chronic disease found obesity and various chronic diseases worsened between 2002 and 2012 across China. National health and nutrition surveys have repeatedly linked obesity with health problems in groups with poor diet.

Official nutritional advice from the government recommends eating less red meat, poultry and seafood, and there are signs that consumers are listening.

After peaking at 42 million tonnes in 2014, China’s pork consumption dropped slightly to 41 million tonnes in 2016, bucking a rising trend. Leading producers of frozen dumplings, such as Wanchai Pier and Sinian have even reduced the amount of pork in their products in recent months.

People are also eating more fresh fruit and vegetables, according to data from Euromonitor, which recorded an increase of 4% in 2016. China now consumes 40% of the global total.

China consumes 40% of the world’s fruit and vegetables

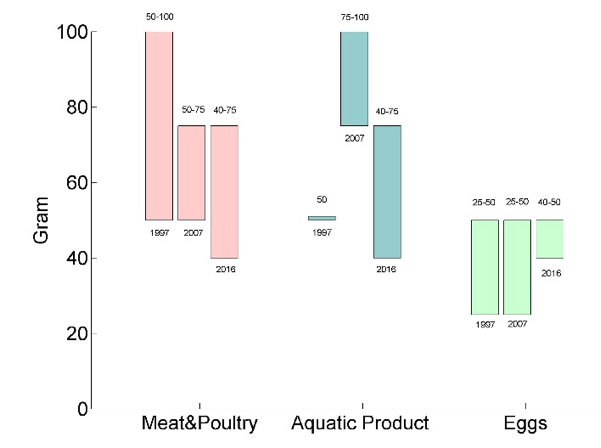

Recommended daily consumption of meat and poultry, seafood and eggs in 1997, 2007 and 2017. Source: China Nutrition Society

Health campaigns are also trying to influence people’s habits. Environmental group WildAid held an event in Beijing in August 2017 to promote vegetarianism.

The actor Huang Xuan explained that his family is eating more and more vegetables, a change from the traditional diet in his native province of Gansu in China’s north-west, which is high in beef and mutton.

“My family eats very little meat now, and rarely orders it when eating out. It’s a natural change,” said Huang.

He thinks it’s because people are more aware of the links between meat-eating, high blood pressure and obesity.

The Beijing Farmers' Market is Beijing's longest running market selling organically grown food (Image: 北京有机农夫市集/weibo)

The Beijing Farmers' Market is Beijing's longest running market selling organically grown food (Image: 北京有机农夫市集/weibo)

Middle class tastes

China’s middle class in particular seem to be shifting toward diets that focus more on quality, style and health.

Diets are focusing more on quality, style and health

There is no consensus on the size of China’s middle class, but everyone agrees that it’s huge. Credit Suisse’s 2015 report on global wealth put it at 109 million people – larger than in the United States. Consultancy group McKinsey predicts China’s middle class will include 400 million people by 2020, with half of these in the “upper middle-class” bracket, earning between 106,000 and 229,000 yuan (US$ 16,500-35,600) a year.

Growing incomes are having a noticeable effect on food trends, including a greater willingness to pay more for higher quality, healthy foods.

Gu Shaoping, a senior official at the National Certification and Accreditation Administration, told an industry conference that organic food sales in China grew about 18-20% in 2017.

Data from Euromonitor shows double digit percentage growth for consumption of organic foods in China annually between 2012 and 2016, prompting more producers to go organic. While the past ten years have seen numerous organic farms providing products free from fertilizers and pesticides spring up around Beijing, including Little Donkey Farm, Phoenix Commune and Shared Harvest.

More than diet

Changes in eating patterns are connected to deeper changes in how people think about food. The growth in organic food is part of a broader promotion of vegetarianism and an understanding of the links between food and the environment, particularly in cities.

WildAid is promoting vegetarianism to cut meat consumption and so reduce the environmental and climate impacts of livestock farming.

Similarly, Jian Yi, the independent filmmaker behind the What’s For Dinner documentary, has started a Good Food Academy website and launched a nationwide lecture tour – hoping to increase awareness of how food is produced and consumed so people will realise the true costs of food, again with the aim of improving the environment and public health.

But it is hard to say to what extent consumers are really interested in issues such as agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and the environmental impact of industrialised farming. Currently, just 0.9% of China’s arable land is used for organic farming, and most of what’s produced is exported.

But the initiatives are succeeding in creating more space for discussion of these issues, and creating pressure for higher minimum food standards. For example, many supermarket vegetables now have tracking labels, so shoppers know the origin of their food.

Global impacts

The enormous purchasing power of China’s middle class is a major force affecting global food production.

Pork consumption may have peaked in China, but seafood and beef are still rising. According to Bloomberg Intelligence the amount of beef people eat increased a third between 2012 and 2016. China also accounts for 60% of global aquaculture output.

With readier access to global markets, Chinese people can source their food and drink – be it beef, coffee, rice or fruit – from anywhere in the world.

Take the avocado. UN trade figures show that between 2010 and 2016 China’s imports of the fruit rose from 1.9 tonnes to 25,000 tonnes – an 13,000-fold increase. China’s main avocado suppliers, Mexico and Chile, saw avocado exports rise from 154 tonnes to 50,000 tonnes over the same period, with China a major contributor to the increase.

Fernando Reyes Matta is a former Chilean ambassador to China and head of the China Studies Centre at Adres Bello University.

Regarding an agreement that allows Chilean avocados to enter the Chinese market he told chinadialogue:

“This represents a big challenge for avocado producers, which already have a lot of capacity to export, but which have a long-held ambition to export to the Chinese market. This will have a very significant impact on Chile's agro-industrial exports.”

In 2015 Chile signed an agreement with China on the export of avocados and it soon overtook Mexico to become China’s biggest supplier.

Avocados may be healthy but growing them requires huge quantities of water. Matta says growth in the sector has added to conflicts over water between Chile’s farmers and the mining industry.

But it isn’t just health concerns that are shaping the food habits of China’s middle class – quality, taste and status are factors too. This has led food suppliers to make some ethically questionable decisions.

Last July a popular Chinese shopping site, JD.com, announced with great fanfare it would be selling Australian Southern bluefin tuna, a species classed as critically endangered by the IUCN. Criticism from conservation groups was swift and sparked a fierce debate.

China’s consumption of shark fin and totoaba maw also encourages cruel practices such as shark finning and even threatens the survival of endangered species elsewhere in the world.

Be it shark fin, sea cucumber, or an ordinary bowl of dumplings – China’s changing appetite is already having lasting impacts on the global environment and will continue to for decades to come.