The catastrophic burning of the Amazon has focussed a great deal of attention on forest fires, but the use of fires in traditional cultivation methods by indigenous populations has not led to this, and must not be confused with this. In South Asia, across the northeastern states of India, and in Bangladesh’s indigenous areas controlled burns for cultivation, called jhum agriculture, have not led to this type of devastation. – eds

As thousands of fires rage across the Amazon, world headlines have highlighted the associated illegal deforestation and international outcry. But the implicit categorisation of all these fires as “wildfires” or even just “bad” fires hides the fact that fire is also used sustainably in the region. In fact, for numerous smallholders and Indigenous peoples, it is part of their livelihood and cultural practices.

The Amazon isn’t one continuous block of lush rainforest as in the Western imagination, but rather a landscape of multiple ecosystems including forest, wetlands and savannas. Indigenous and local communities use fire within these habitats in different ways.

For example, fire is used in small-scale rotational forest farming where typically half hectare plots are cut, burned and planted for a number of years, before being left to regenerate. And in the fire-prone savanna, Indigenous people use fire to drive and trap game such as deer or the pig-like peccary.

Key to traditional fire management is the burning of small areas at different times over the whole dry season, thus producing a mosaic of burnt and unburnt patches across the landscape. This reduces fuel loads, introduces natural firebreaks, and limits the potential for catastrophic fires.

For many Indigenous groups in the Amazon, their entire way of life is predicated on sustainable fire. For example, the Mebêngokrê (Kayapó) people, who live in a remote region of the Brazilian Amazon, use fire to hunt for tortoises. Fire is used to clear tall savanna grasses thus making tortoise burrows more visible and accessible. Hunts like this form part of extended traditional festivals with implications for social processes including courtship, community cohesion, youth initiation and inter-generational knowledge transfer.

The Wapishana and Makushi, in neighbouring Guyana, use fire for gathering resources such as burning along swamps before cutting palm leaves, smoking bees before collecting honey, and stimulating certain trees to fruit, as well as using fire to protect important areas such as sacred forests, farming plots and homes. For all these groups, fire intimately connects livelihoods, culture, history and beliefs.

Anti-fire discourse

Indigenous management has a wider impact: evidence from several satellite studies indicate that Indigenous lands have less deforestation and habitat conversion compared to surrounding areas. This means these areas are more biodiverse and store more carbon.

Yet, there is still a pervasive anti-fire discourse targeting Indigenous peoples and smallholders in the Amazon. In Venezuela, for example, the Indigenous Pemón have been labelled with the derogatory phrase “Pemones los quemones” (crudely translated as “Pemón the pyromaniacs”), and in Brazil there is a notion that Indigenous burning activities represent an inherently destructive mentality. This anti-fire rhetoric is widely used by interest groups in the Amazon, such as the powerful agribusiness lobby, to discredit Indigenous and local communities and as political narratives contesting rights to land.

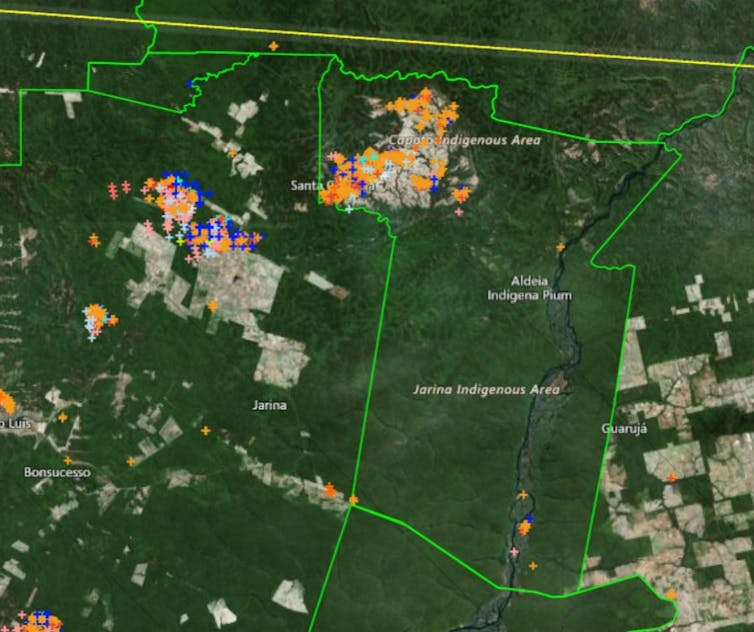

It does not help that the satellite imagery currently used to monitor fires in the Amazon is typically 4km x 4km resolution – that is, it can only “see” in blocks of four kilometres. That means it cannot distinguish between small, controlled fires – perhaps only the size of a field, but large enough to trigger the satellite – and much larger wildfires.

Conflating distinct fire types – small, large, controlled, uncontrolled, intentional, accidental, sustainable, unsustainable – raises more problems. It impedes our understanding of the root causes of destructive wildfires, and aids the formulation of restrictive policies that further disempower already marginalised groups while giving more power and control to established hierarchies.

Climate change is a reality for marginalised groups in the Amazon, where drought produces more flammable forests. In a vast region with limited infrastructure, resources and on the ground enforcement, firefighting alone is not viable and not effective, today or in the future.

At the G7 summit, a group of wealthy nations pledged USD 22 million for firefighting planes and military support to tackle the Amazon fires. But it’s a top-down, sticking plaster approach. That money may be much better spent on strengthening Indigenous and local community land rights, while supporting local communities to share their fire knowledge with decision-makers in order to revalorise and implement traditional fire management grounded in local realities and a changing climate.

This piece was originally published in the Conversation.

![<p>Active fire detections in Brazil as observed by Terra and Aqua MODIS between August 15-22, 2019 [image courtesy: NASA]</p>](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2019/08/NASA-amazon-1.jpg)