Saing Puy has been waiting a decade for compensation. She represents 77 of the families in Cambodia’s southwestern province of Koh Kong displaced by a US$3.8 billion Chinese megaproject called Dara Sakor.

Back in 2008, Tianjin Union Development Group received a 99-year land concession for 36,000 hectares within Koh Kong’s heavily forested Botum Sakor national park, home to rare flora and fauna, including endangered mammals like the pileated gibbon.

So far, Dara Sakor consists of a luxury resort with a golf course and casino. Future plans include a deep-water port, an international airport (with flights starting next year), an industrial park, power stations and a water-treatment plant.

Empty promises

While awaiting compensation, Saing Puy travelled to Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh several times to seek intervention from the ministries of land management and environment, as well as from the Chinese embassy. She received only promises.

“A decade ago, my family lost our land,” said Saing Puy, who lives on the small island of Koh Sdech, just off the coast. “The company tore down my house and banned us from using our farmland. Now I live near my land awaiting a resolution.”

She said that when Tianjin Union Development Group came they said they would build infrastructure – roads, a school, a health centre – so people were excited about the development.

“Instead, they built a hotel, casino and golf course and forced us to relocate.”

More than 1,000 families were evicted from Koh Sdech. The company cut down trees to construct roads and make way for new homes for those displaced.

“Before the company came, we had difficulty travelling because we had no road, but we had no problem supporting our family. We had our fishing jobs, and our farmland,” she added. “Now we have good roads, but we’ve lost our land, jobs and forest.”

Access denied

Forty-six-year-old Mai Pov is among dozens of families in the Koh Kong province’s Kiri Sakor district engaged in long-running land disputes with Tianjin Union.

“For eleven years I have not cultivated my land since [Tianjin Union] came and stopped allowing us access,” she said. “Now I am trying to net fish at sea and grow rice on another small bit of land.”

“We are not against the development project but they have to give suitable compensation and not grab our land like that. Local authorities have never settled the villagers’ problem. They always side with the company,” Pov said.

Since the 99-year land concession in 2008, government figures show it has handed over an additional 9,100 hectares to Tianjin Union, affecting 1,963 families.

Wang Chao, vice president of the group declined to comment.

Sok Sothy, Koh Kong provincial deputy governor, said that the government is responsible for setting aside land for citizens who live on state-owned forested land. However, he accused the remaining protesters of being “outsiders who just claim they have land in the protected area. The authorities have no policy to help them”.

Citizens say they will continue to protest at the relevant ministries and institutions until there is a suitable resolution for them, as they have lived on the land for many years.

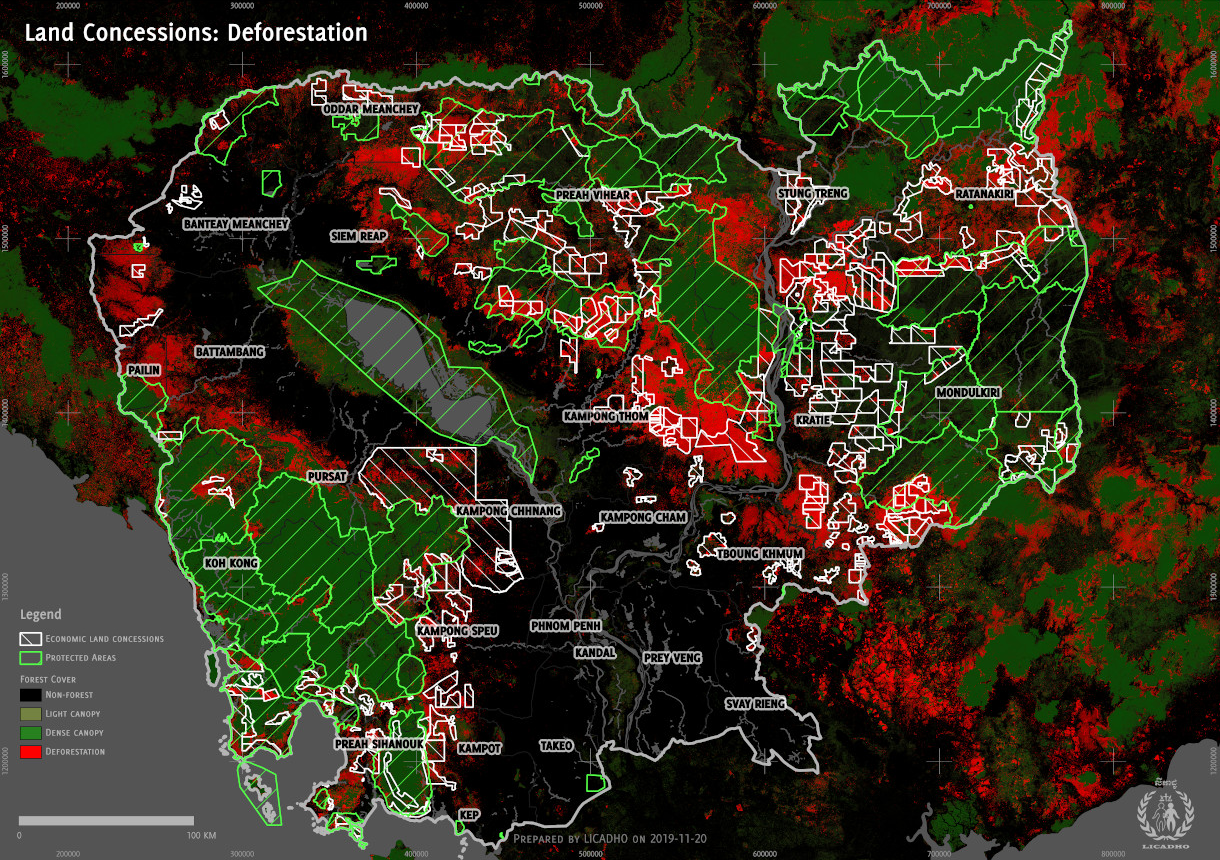

Click image to enlarge (Credit: Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights)

Social impacts

Ouch Leng, director of Cambodia Human Rights Task Force, said there were irregularities in the allocation of compensation to villagers and those who participated in protests had been threatened with lower compensation.

He added that families’ livelihoods were destroyed after Tianjin Union forcibly relocated them from Koh Sdech island to a place without basic facilities such as a school and hospital.

“Some people who used to get at least $150 a trip from fishing are now earning just $5 a day doing construction for the company.”

According to Ouch Leng, some provincial authorities and district governors were found guilty of corruption and dismissed or fled to avoid legal responsibility. The relocated people find themselves in a protected area in the middle of the mountains. The law prohibits them from clearing any land to farm. Thousands have emigrated to Thailand for work. Hundreds of others have risked going back to the coast to fish again.

“I have tried to make strong interventions at the national level,” said Ouch Leng. “The provincial authority and resolution committee have tried to ignore [us] for years in order to hide their collusion and corruption in the resolution process.”

He alleges that the money meant for compensation has been siphoned off by members of the resolution committee. Land titles were revoked by armed men working for the committee and people were given as much as $2,000. In fact, a five-hectare piece of land is worth at least $40,000.

“If the owner did not accept $2,000, they were told to look towards the back of the room where a rifle hung on the wall.”

Growing Chinese investment, trade and tourism

Data from Maybank and the China Global Investment Tracker found that Chinese investment in Southeast Asia almost doubled in the first half of 2019 to $11 billion, compared with the second half of 2018. Cambodia received $2.5 billion in the first six months of the year, the second-largest amount of BRI investment of any country in Southeast Asia, after Indonesia.

According to official data from the ministry of economy and finance and the Cambodia Development Council, China is Cambodia’s top investor and donor. From 1994 to 2016, Chinese investment there was about $15 billion.

Cambodia’s exports to China rose sharply during the first 11 months of 2017, by as much as 18% year on year, according to the latest data from the ministry of commerce. Total exports to the Chinese market reached $634 million from January to November 2017. Meanwhile, imports from China experienced a more moderate growth, rising from $4.33 billion in 2016 to $4.48 billion last year.

In 2015, Cambodian prime minister, Hun Sen, announced his intention to attract one million Chinese tourists in 2018, and two million by 2020. According to data from the ministry of tourism, Cambodia achieved that goal a year early. Currently, 155 direct flights operate from China to Cambodia each week.

More jobs, fewer casinos

Sophal Ear, an associate professor at Occidental College in Los Angeles, believes what is needed is “more factories and fewer casinos and empty condos. You want to add value, not just launder money and build for no one to live in.”

He added that the special economic zone being developed in Koh Kong could be beneficial, but not if the idea is to make goods in China, send them to Cambodia for minimal processing, and then re-export them with a “Made in Cambodia” label stuck on. “Only the officials make money that way.”

“What’s really needed is to think strategically about the best kinds of investments for Cambodia – how to add value and create jobs. Cambodia needs to move up the value chain. China could help Cambodia do this, but it takes work and effort. Officials in Cambodia are not interested in that – easy money is too tempting.”