Editor’s note: The Kunming biodiversity COP15 is likely to be postponed in response to Covid-19.

In October this year, governments from around the world are due to adopt a new global agreement to stop the loss of nature on land and in the ocean, at the most important biodiversity conference in a decade – COP15. The 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), is set to be hosted by China in Kunming. It will be the first time the country has hosted a major international environmental meeting.

The Kunming meeting should shine a spotlight on the state of nature in the world, as well as draw attention to the situation in China and how the government has responded domestically. China’s international interests, including the greening of the Belt and Road Initiative and its relationships with other major powers, may also play a critical role in shaping the process towards Kunming and the follow up.

Another crucial UN meeting is scheduled for one month after Kunming. The UK is hosting COP26, this year’s meeting of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, in Glasgow. Its overriding aim is to raise the level of ambition across countries in curbing greenhouse gas emissions.

While China appears to have successfully suppressed Covid-19, the virus is spreading nearly everywhere else. The economic consequences are projected to be dire, and the emergency response is taking attention away from the issues of protecting biodiversity and halting climate change.

Both the Kunming and Glasgow meetings may have to be postponed. Yet, the pressing issues they need to tackle will not go away. So at some point in the near future governments will come together under Chinese and UK leadership to thrash out a strategy for protecting nature and the climate.

Policymakers, business leaders and civil society therefore need to have a clear understanding of the issues involved and how to address them in an integrated manner. Fortunately, there is a compelling narrative to be told that draws on domestic achievements in China as well as a growing body of scientific evidence.

A landmark 2019 study showed that the world is losing nature at unprecedented rates. Many scientific studies have laid out targets that need to be met to halt this biodiversity loss. We also know that protecting and safely managing nature can contribute about one third of the greenhouse gas emission reductions required to achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement. And that protecting nature is critical to improving societies’ resilience to climate change.

For this reason, the preparation of the Kunming biodiversity meeting has focused on targets for nature conservation. Arguably, though, implementation is even more important. After all, the CBD has adopted ambitious targets in the past, including the Aichi Biodiversity Targets to be reached this year. Yet these and earlier targets have largely come and gone. They have not made a significant difference to the loss of nature around the world.

Implementation is a massive challenge for even the wealthiest countries. Germany, for example, has one of the strongest green movements in the world. Yet the country has lost three quarters of its flying insects since 1989, signalling a wider loss of nature.

Ecological conservation redlines

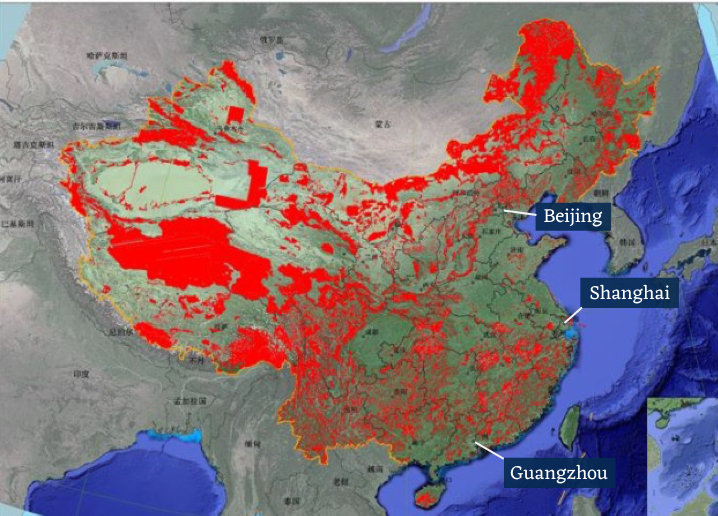

In 1998, catastrophic floods hit the Yangtze River valley, much exacerbated by overdevelopment of grasslands and wetlands that would otherwise have helped absorb the floodwater. China responded in 2000 by piloting a policy of ecological conservation redlines. Between 2010 and today, over a quarter of the country has been included in the redline – meaning put under protection or sustainable management. The aim is to protect almost all of China’s endangered species and their habitats, with simultaneous gains for the prevention of floods and sandstorms, provision of clean water and other ecosystem services. Implementation of the policy is overseen by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and supported through fiscal transfers from the national government, payments for watershed management and other market-based instruments.

China’s experience may be relevant for any country wishing to meet the objectives of the CBD and the Paris Agreement.

Ecological conservation redlines in 2019. These initial delineations may change as the policy is still being rolled out in 15 provinces in China. (Image: Presentation by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment)

The ecological conservation redlines are part of a comprehensive land-use planning framework under development by the Ministry of Natural Resources. The ministry is developing a 15-year plan for land use covering ecological needs, agriculture, cities, industry, major infrastructure and other uses. The framework is slated to be part of the 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025). To my knowledge, China is the only country practising such comprehensive and ambitious land-use planning.

Moreover, China is committed to greening the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This requires addressing two critical challenges. First, countries need to avoid constructing new fossil fuel power plants. Second, BRI countries need to design and build infrastructure that maximises economic and social benefits and minimises negative environmental impacts. For example, roads should not be built through virgin forests, since we know that leads to rapid deforestation and biodiversity loss.

Sustainable road construction is possible, but requires careful spatial planning. Similarly, hydropower can be a boon for sustainable development, but care must be taken to avoid biodiversity loss or adverse impacts on downstream communities. Some BRI projects would likely not proceed or be massively redesigned if the countries they are located in had land-use planning frameworks akin to China’s ecological redlining.

China’s interests will be well served by supporting BRI countries in developing their own land-use planning frameworks.

These will also play a major role in implementing biodiversity targets to be adopted at the Kunming meeting. They are equally needed to meet the mitigation and adaptation targets under the Paris Agreement.

Including land-use maps in climate and biodiversity strategies would aid the success of the Kunming and Glasgow meetings. China can lead the way by referencing the land-use planning framework in its long-term climate strategy.

Such a strategy makes good sense from a climate and biodiversity perspective. But it is also good economic and foreign policy.

On the economic front, governments are considering massive stimulus programmes to support their economies during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. Such stimuli should include large-scale investments in infrastructure, particularly in emerging economies. It is, of course, vital that such infrastructure be consistent with the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero by mid-century and the imperative to halt and reverse the loss of nature. Land-use planning, as practised in China, will be a critical tool for directing the economic stimuli in the right direction.