The largest of all land beasts, elephants are thundering, trumpeting six-tonne monuments to the wonder of evolution. From the tip of that distinctive trunk with its 100,000 dextrous muscles; to their outsize ears that flap the heat away; to the complex matriarchal societies and the mourning of their dead; to the points of their ivory tusks, designed to defend, but ultimately the cause of their ruin.

African and Asian elephants are more closely related to the woolly mammoth than to each other. The ears are said to be a geographical guide. In Asia, elephants have smaller India-shaped ears. While in Africa their huge ears are the shape of the whole continent.

Where do they live?

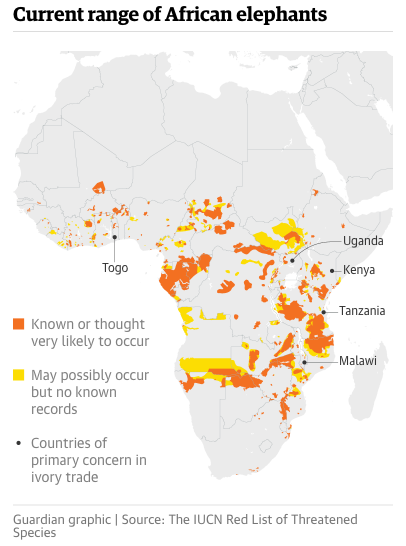

Asian elephants used to roam from the coast of Persia through India and southeast Asia and deep into China. In Africa, they could be found in almost every habitat from the shores of the Mediterranean to the Cape of Good Hope. Most common in the savannahs, elephants still inhabit a wide variety of landscapes. They can be found in the Saharan and Namibian deserts and the rainforests of Rwanda and Borneo. But their range has shrunk and they are now extinct in the Middle East, on the Indonesian island of Java, northern Africa and most of China. Almost everywhere, these great nomads are restricted to ever-decreasing pockets of land.

A

All about the ears: Asian elephants have smaller India-shaped ears, while those of their African cousins are huge and in the shape of the whole continent. (Image by JULIAN MASON)

How many elephants are alive around the world?

In 1800 there may have been 26 million elephants in Africa alone, although it’s hard to be precise. But today, after years of poaching and habitat destruction, those numbers are a tiny fraction of what they once were.

In Asia, it is estimated that less than 50,000 elephants remain; more than half of them in India. Tiny populations, a few hundreds or thousands, cling on in countries across south-east Asia and the Himalayas.

In Asia, it is estimated that less than 50,000 elephants remain; more than half of them in India. Tiny populations, a few hundreds or thousands, cling on in countries across south-east Asia and the Himalayas.

In Africa, the larger of the two species is a step further from extinction. Less than half a million roam the continent, mostly in the southern states. In the west and the forested centre, elephants are in a particularly perilous condition.

What has caused the destruction of elephants?

For thousands of years ivory has been prized and elephants have been killed for it. The Egyptian pharoah Tutankhamun was laid to rest around 1323BC on a headrest of ivory, while in nearby Syria elephants were more or less wiped out for their ivory by 500BC.

The invention of guns increased the pressure. The 19th century brought a fashion for big game hunting among colonialists, which wiped out herds across the continent of Africa. Now the remaining dwindling numbers face the threat of local hunters and modern poaching gangs, financed by Asian syndicates and armed by the conflicts of Africa.

Some experts see the brutal killings of elephants not as a battle for a commodity, but for land. As the human population booms, so does demand for space. Poaching conveniently removes elephants from the land, leaving it open to development. This is a pattern seen across western Africa, where elephant declines have been most precipitous. By 2050, 63% of remaining elephant rangelands will be compromised by human encroachment.

The tightly-contested rural landscapes of Asia have seen a more direct form of conflict between humans and elephants. In an evening’s feeding a herd of elephants can destroy the annual crop of many small farmers. Human lives are also in danger. In India, panicked or enraged elephants kill more than 400 people each year (pdf). This leads to retaliation. Wildlife authorities often hunt down and kill problem elephants. In Indonesia, dozens of elephants are poisoned by palm oil growers each year.

Uncovering the “elephant holocaust”

As Africa’s nations shook off colonial rule in the years following World War II, a huge poaching crisis arose. British zoologist Ian Douglas Hamilton, who flew a light aircraft over sub-Saharan African countries to count elephants in the 1970s and 80s, uncovered what became known as the “elephant holocaust”. He estimated that African elephant numbers fell from one million to 400,000 during the 1980s.

Without the often dangerous work of Hamilton, governments would not have come together to ban the international trade in ivory in 1989. This led to a recovery in elephant numbers until 2008, when infiltration of the ivory trade by criminal gangs, rising Asian demand and high levels of corruption increased the levels of poaching with catastrophic results.

How many elephants are killed a year for ivory?

Around 20,000 African elephants were killed last year for their tusks, more than were born. Chinese wealth is financing a hunger for ivory that threatens to bring an end to wild elephants within our lifetime.

There has never been a more dangerous time to be an elephant. Not during the industrial pillaging of the colonial era, nor the chaotic African and Asian independence movements that sparked a 1970s poaching boom, has an elephant been more likely to fall to a gun.

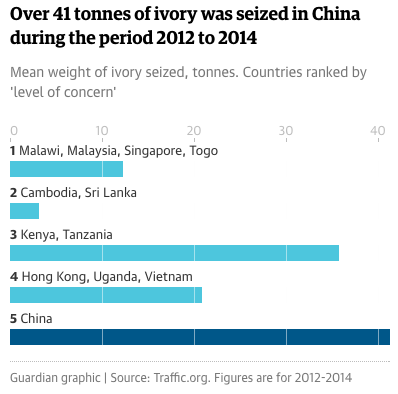

In spite of the global ban on international trade (overseen by the UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species – Cites) the illegal ivory trade has exploded. Some believe large amounts of ivory has also been bought and stored in secret warehouses by investors needing somewhere to hide money from the global downturn. Criminal gangs bribe officials to ship huge quantities of ivory through the ports to illicit factories and markets of China, Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand in particular. In 2011, seizures hit a peak of 23 metric tonnes – 2,500 elephants. But that is only a fraction of what makes it through undisturbed.

What should we do with ivory stockpiles?

Some African states – including Namibia, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Botswana – are arguing for the right to sell off their ever-growing stockpiles, fed by both seizures and natural deaths, in order to help fund conservation work.

But ivory sell-offs – such as the two in 1999 and 2008 – have been also criticised for increasing demand, although there are some who dispute these findings. Another sale has been mooted by Zimbabwe and Namibia and will be discussed at Cites’ triennial conference this September. Many states have burned their stockpiles for symbolic and practical reasons.

Is it still legal to sell ivory?

In many countries ivory can be sold legally, usually sourced from stockpiles or from elephants killed before the ban, allowing antiques to be traded. Cites has raised concerns that unregulated domestic markets in China, Japan, Myanmar and Vietnam allow freshly killed ivory to join legal stock on the shelves, fuelling the poaching crisis.

What can we do to halt the decline?

What can we do to halt the decline?

1) Protect habitat

Efforts to protect Asian elephants focus immense pressure on land and habitat. Poaching exists on the continent, but it is a lesser threat compared to the destruction of their homes. Unlike their African cousins, only Asian bull elephants have tusks. Elephant protection relies on the defence of reserve land from legal and illegal encroachment, logging, roads and other developments. Innovative solutions can help, such as a project in the tea fields of India which uses an SMS warning system so that humans can coexist safely with elephants.

2) Reduce demand

In the markets of Asia where the majority of the poached African ivory ends up, the holy grail of elephant conservation remains the abolition of demand for ivory. This has worked in Japan – what was one of the biggest markets for ivory at the turn of this century is now a minor player.

In China, advertising campaigns featuring local and foreign celebrities are having an effect. The proportion of Chinese who believe elephant poaching is a problem grew from 47% to 71% between 2012 and 2014. This awareness also appears to be having an effect on policy. The Chinese and US governments have agreed to work together to end the global illegal ivory trade. Last year, China began to phase out its domestic manufacture and sale of ivory and the US cracked down on its own internal market, which was the second largest in the world.

The proportion of Chinese who believe elephant poaching is a problem grew from 47% to 71% between 2012 and 2014. (Image by shadesofgrayden)

Meanwhile the Europeans – historically responsible for a great part of the decline of elephants during colonial-era craze for big game hunting – have drawn criticism for refusing to back a long-term end to all trade in ivory. Some observers argue that the only way to save elephants is to give them economic value. That can mean emphasising the value to tourism, but the EU has raised the possibility of allowing states where populations are stable to harvest ivory and sell it to China legally.

3) Support the frontline defenders

The link between poaching and poverty is clear: rates of infant mortality and poaching activity correlate strongly. In Kenya, a poacher makes US$3 (20 yuan) per kilo of ivory, a princely sum compared to the daily earnings of many around them. But the gangs they sell it to get $1,100 per kilo for the same tusk in China. Many elephants, particularly in the forests of central Africa, are not only targeted for their ivory. An enterprising hunter can make more money in the unregulated bushmeat markets from the smoked meat than from the tusks. So the development and prosperity of rural Africa is a vital aspect of elephant conservation.

In the face of this multitude of threats, inspirational work is being done by exceptionally brave people. In Kenya, former poachers are recruited to be the world’s first line of defence against the murder of elephants – the park rangers. All too frequently they lose their lives. These people, the NGO community and the efforts of many governments are sources of hope. The defeat of greed and desperation may be hard to imagine. But try imagining a world without elephants.