Autumn again and countless birds are preparing to fly south for the winter, unaware of what their journey will bring. During China’s National Day holiday in early October, volunteers took down two large swathes of illegal bird nets, stretching over 20 kilometres.

Over 8,000 birds were trapped in the nets, with only 3,000 of them still alive. Many Chinese people watching this on the news were unaware of the mass slaughter of wild birds being carried out in the countryside around their cities.

Net gains, net losses

Members of the China National Net Removal Centre have been busy lately. The 300 members of this WeChat social media group are dedicated to taking down bird nets found in forests, reeds, and farmers’ fields. Some are over 10-metres high and 40 or 50-metres long. Wherever nets are found the voluntary teams take them down.

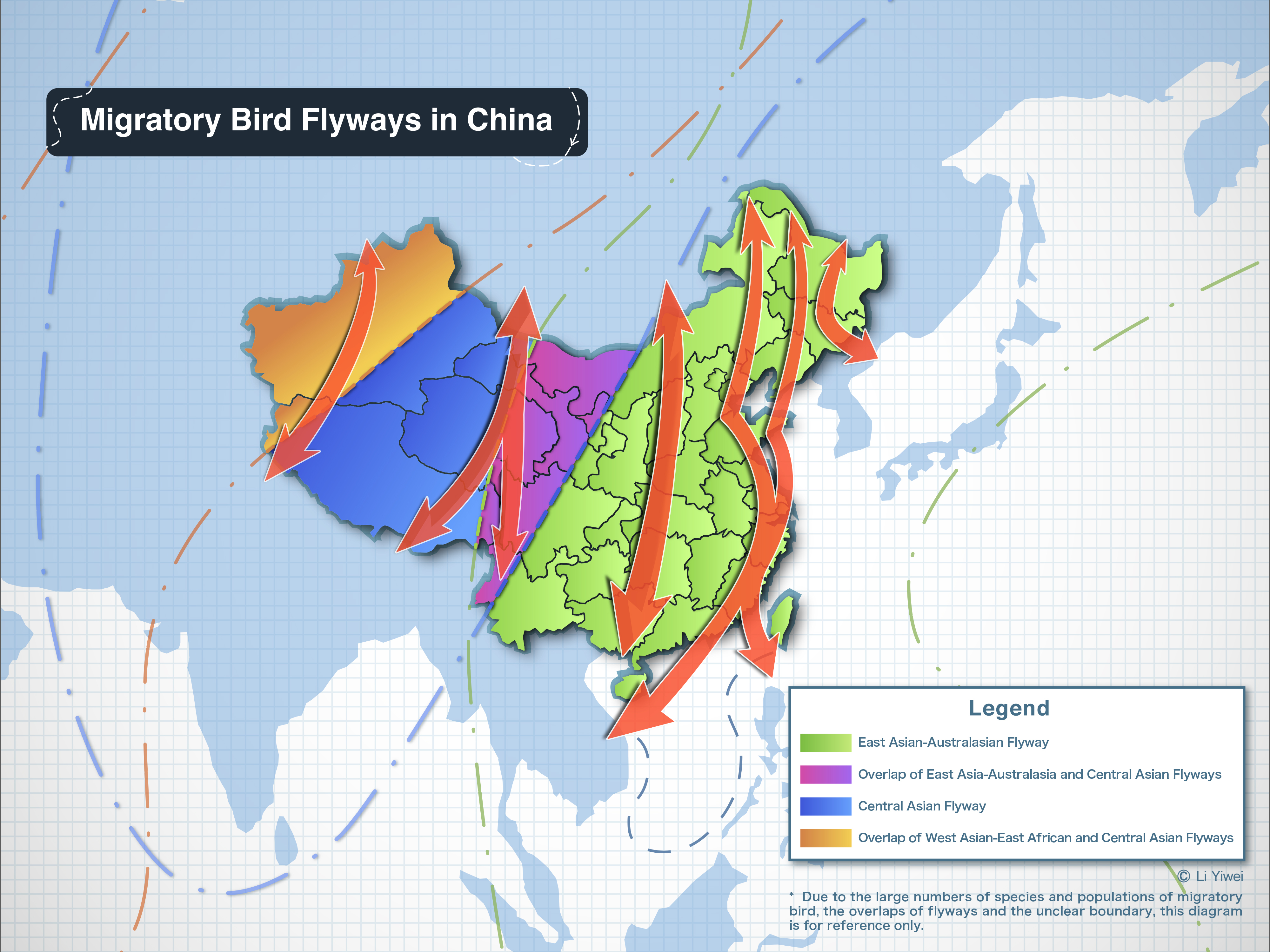

At this time of the year the number of clashes between trappers and activists spikes. A number of important migratory pathways pass through China each year. Populous cities such as Tangshan and Tianjin lie on the East Asia-Australasian flyway, used by around five million birds travelling between Alaska in the north-west and south Asia. Bird trapping is rife along the China-stretch of this path which has become a battleground for removal teams and hunters.

Liu Yidan, China’s best known volunteer bird conservationist, is mainly active around Tianjin, a big industrial city north of Beijing. She told chinadialogue that she has freed 40,000 birds so far this year.

Migratory flyways pass through populous areas, which are often rich in resources and suitable for both agriculture and industry. This can bring people and birds into conflict. Image: WWF China / Li Yiwei, Zhang Yimo

Those concerned about the safety of migratory birds have been able to find each other and connect via social networks. The WeChat forum used by many of the net-removal volunteers keeps its 300 members up-to-date on efforts to save the birds.

Blogs and other online platforms facilitate discussions between the animal rights activists and the public. One volunteer who blogs under the pseudonym “net removal worker” writes in one article about taking down 90 bird nets in six days in the township of Chenjia, on Chongming Island, Shanghai. Chongming is known as a winter refuge for migratory birds.

E-retailers must take responsibility

But the nets are going up faster than they can be taken down. The volunteers have found that online shopping sites have spurred the trade in captured birds. They complain that Taobao, China’s largest online retailer which is owned by Alibaba, has made it easier and cheaper for hunters to acquire tools, meaning disaster for migratory birds and other animals.

A search on Taobao for “bird nets” brings up 5,000 suggested purchases, including one net that is 5-metres high and 30-metres wide for only 30 yuan (US$5). Cheap prices and quick delivery makes acquiring nets simple.

One volunteer, who preferred to remain anonymous, complained that: “Nets, lures; you can get anything you want on Taobao, and the sellers even tell you how to use them. E-commerce has sent the bamboo partridge to the brink of extinction.”

The trade in captured birds is also increasingly reliant on the internet. A 2014 report from the International Fund for Animal Welfare, Wanted – Dead or Alive, Exposing Online Wildlife Trade, exposed illegal online trading of many CITES Appendix 1 and 2 listed endangered species. In China the online trading of live wild birds takes place on sites like Alibaba’s Taobao, second only to that in turtles and tortoises.

A net hidden in the trees. Source: “Net removal worker” blog

The industry behind the nets

Zhang Yimo, head of the WWF China’s migratory birds network, told chinadialogue that flyways in China are much more densely populated than in other places where migratory birds rest, such as Russia and Alaska. And so the birds come into conflict with people more often, relatively speaking.

The netting of the birds is just one part of a business. Many of the wild creatures are then sold to restaurants in large numbers. In the chat room one volunteer reported large numbers of nets in a Zhejiang tourist spot, with restaurants openly advertising wild-caught game. The Yellow-breasted Bunting, once a common sight, is now as endangered as the Giant Panda.

Also, some Chinese people like to keep birds as pets, and a rare songbird can mean huge profits. According to one volunteer, one Siberian Ruby Throat hummingbird, known for its pleasant song, can fetch as much as 8,000 yuan (US$1,156).

Effects of new law remain to be seen

Zhou Haixiang, head of the Ecology and Environment Laboratory at Shenyang Ligong University, does not think taking down the nets will prevent trapping. He told chinadialogue that this has no deterrent effect and that efforts should be directed towards catching the poachers.

“A net is cheap, you take one down and they will put another up,” said Zhou Haixiang.

Some of the volunteers are disappointed by the lack of law enforcement. “Net removal worker” wrote on his blog:

“Just taking the nets down simply isn’t enough. If you don’t strike at the people trapping birds, trading birds, eating birds and keeping birds then you can take down as many nets as you like but they will just get put back up.”

The punishment for trapping birds under Chinese law is minor but the potential profits are huge. For many it is worth the risk. Zhou Haixiang explained that in some places farmers make several thousand yuan a year by planting crops. However, you can make more, and faster, by spending a few days trapping birds during the migration season.

Zhou thinks the most effective approach would be to fine anyone caught with a wild migratory bird, regardless of whether they are the buyer, seller, or poacher.

There are differing opinions on whether the new Wild Animal Protection Law, due to come into effect in 2017, will offer much protection to migratory birds. The sale of nets online will be restricted, as the law is expected to ban online trading platforms from allowing the illegal sale of wild animals and hunting implements. It also bans the use of poisons and nets to hunt wild animals.

Xie Yan, a deputy researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Zoology, said that the new law is the first law designed to protect the birds’ habitats and to ban hunting, including on the migratory routes of birds that are not necessarily protected species.

But Zhou Haixiang thinks the law still focuses too much on the protection of rare and endangered species, rather than the ecosystem as a whole.

More importantly, it’s hard to see the new law having much impact if enforcement isn’t improved.

“The question now is how to ensure the law is strictly enforced,” said Liu Detian, head of the Liaoning Panjing Society for the Protection of Chinese Black-headed Gulls. Under the law, the poaching of more than twenty wild animals is to be treated harshly; and one net can easily catch hundreds of birds. Lu thinks law enforcement agencies aren’t doing enough to combat bird netting, and imposing fines just means the poachers trap more birds to cover the costs. He thinks prison sentences are needed to solve the problem.

According to Zhang Yimo, as the internet makes it easy to buy and sell trapping tools and wild animals, there is a need for the authorities in charge of online commerce, businesses and wildlife protectors to cooperate. The roads and railways authorities, including delivery firms, should also work to prevent breaches of the law.

On October 18, the State Forestry Administration launched a 40-day “Net Clearing Action”, intended to remove illegal bird nets and smash the underground networks trapping, transporting and trading trapped birds. So perhaps this migratory season, the volunteers will have a bit more official support and the birds will face less danger. But as Zhang Yimo says, to ensure the long-term safety of migratory birds, “strong law enforcement is crucial, and that will be very hard to achieve.”