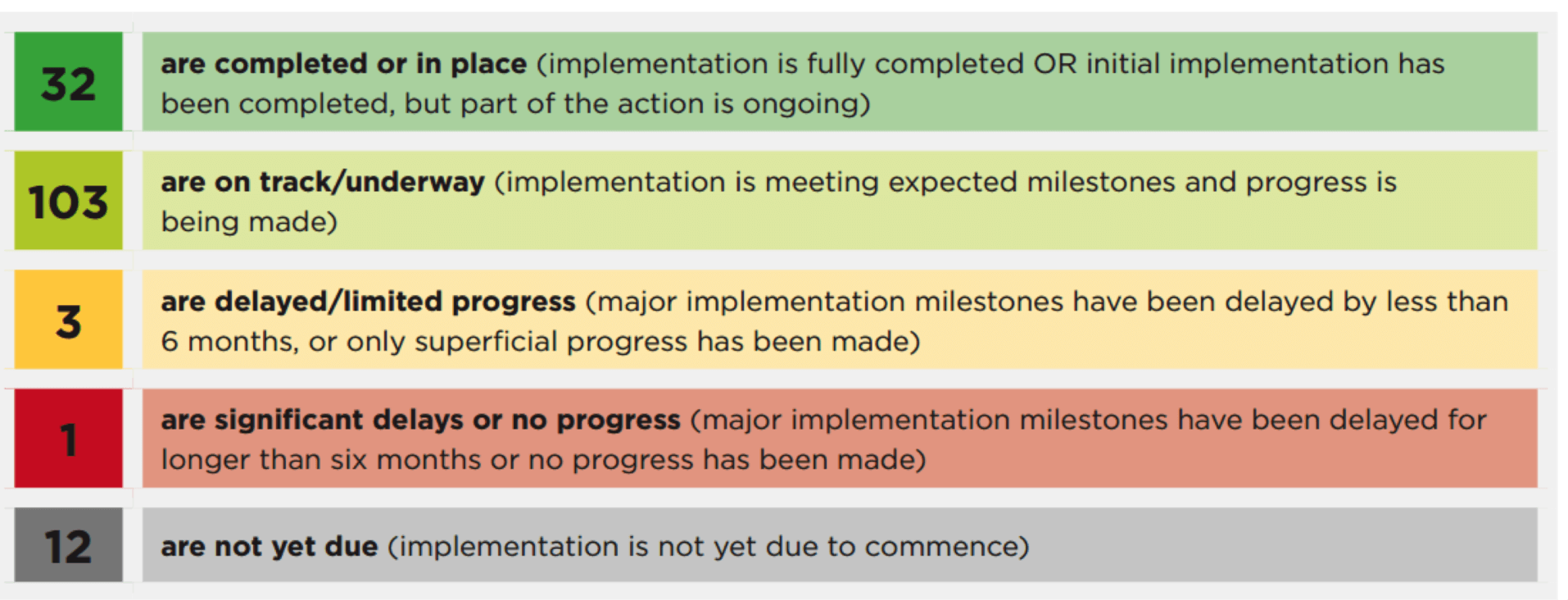

The update on the Reef 2050 Plan suggests that 135 of the plan’s 151 actions are either complete or on track.

The Australian government’s apparent intention in releasing five recent reports is to reassure UNESCO that the Great Barrier Reef should not be listed as “World Heritage in Danger” (as the World Heritage Committee has previously threatened).

Sadly, behind the verbosity and colour of these reports, there is disappointingly little evidence of progress in the key areas needed to make a significant difference to a World Heritage Area that is in crisis.

Also read: Who rules climate intervention on the high seas?

Poor baseline

The government framework for protecting and managing the Reef from 2015 to 2050, the Reef 2050 Plan, has been widely criticised as failing to provide a sound basis for the necessary long-term protection of the Reef.

As well as providing a shaky basis to build effective actions, the Reef 2050 Plan has few measurable or realistic targets. It is therefore not easy to report on the actual progress.

Several of the actions that will have the greatest impacts on the overall health of the Reef are shown in the progress reports as “not yet due”. In some cases, such as climate change, the Reef 2050 Plan is silent, instead simply referencing Australia’s national efforts on climate change.

Instead, the plan is to “[improve] the Reef’s resilience to climate change by reducing local pressures”. Besides addressing water quality, there are many things that should also be considered but they involve making some really hard decisions, such as choosing between coal and coral.

Progress versus reality

The overview of progress claims that 135 of the 151 actions in the Reef 2050 Plan are either completed (dark green) or are on track for their expected milestones (light green), as shown below.

Reef 2050 Plan: Update on Progress, 2016, CC BY

The reality, however, is that many of the 103 of the actions described as “on track/underway” have not progressed as initially proposed when the Reef 2050 Plan was submitted to UNESCO, and that the definition of “underway” is far too loose to be meaningful.

Our rapid assessment of the status of actions indicates that the level of progress reported for at least 32 of these 151 actions (around 21%) has been overstated. The following are just some examples:

The unfortunate truth is that neither UNESCO nor the IUCN has the time or resources to conduct their own comprehensive assessment of the Great Barrier Reef. They rely heavily on these reports when deliberating on what to recommend to the World Heritage Committee, including whether the Reef should be placed on the World Heritage in Danger list.

Our rapid assessment indicates there are real concerns with relying on the government to self-report accurately. It would appear the only way that UNESCO will receive an accurate update is if that assessment is done independently of government. Fortunately, UNESCO and IUCN do consider other evidence.

It is also concerning that the members of the government’s Independent Expert Panel and the Reef 2050 Advisory Committee were not involved in making the final assessments for the 2016 update report.

Despite pronouncements that the Great Barrier Reef remains healthy, the evidence of the 2015 Water Quality Report Card, along with numerous expert opinions (for example, Jon Brodie on water quality; Terry Hughes on coral health; the Queensland government on scallops; and the Marine Park Authority on inshore dolphins) shows that the real situation is not as rosy as UNESCO and the Australian public are being told.

Some real progress, but not enough

It is important to recognise some progress is being made – but sadly too little and not enough to reverse the declining trend for many of the values for which the Reef was listed as World Heritage.

We should also question some of the priorities in the Reef 2050 Plan given the widely acknowledged critical issues (see page 252 in the government’s 2014 Outlook Report). Adopting best practice for water quality from point sources such as sewage discharge (action WQA11 under the plan) and protecting habitat for coastal dolphins (BA12) should be immediately addressed.

Whether we have the money to do what’s necessary is another question. The government’s pledge to spend A$2 billion over 10 years is the current collective yearly spending (A$200 million) of four federal agencies, six state agencies and several major research programs, extrapolated over the coming decade.

While the level of funding is significant compared with many other World Heritage areas, the amount and priorities must be questioned, given that many of the Reef’s values are continuing to decline.

So far most funding has been spent on addressing water quality, and while this has achieved some positive results, it has not managed to stop the deteriorating trends.

As Jon Brodie recently wrote on The Conversation:

The best estimate is that meeting water quality targets by 2025 will cost A$8.2 billion … If we assume that … A$4 billion is needed over the next five years, the amounts mentioned in the progress report (perhaps A$500-600 million at most) are … totally inadequate.

More action needed

The Reef is unquestionably of global significance. Given its sheer size and location, no other World Heritage Area on the planet includes such biodiversity.

The worst-known bleaching event in the Great Barrier Reef demonstrates the limitations of the Reef 2050 Plan, which is silent on the impact of greenhouse emissions from Queensland’s coal mines and the effects of climate change more generally.

Governments have an obligation to protect all the Reef’s values for future generations. To do this they must recognise growing global moves to address climate change, and the widespread national and international expectations that more needs to be done to protect the Reef.

Australia is a relatively rich country and has the technical capability to address the issues. This provides an opportunity to show some global leadership for managing such a significant part of the world’s heritage.

Listing the reef as World Heritage in Danger won’t in itself fix the problems – but it will certainly focus the spotlight on the issues.

As the World Heritage Committee prepares for its next meeting in July 2017, and considers once again whether to officially list the reef as in danger, it will need to study all the evidence, not just the government’s reports.

Certainly the true picture is more complicated and dire than the most recent government reports imply

This article was originally published in the Conversation