Chinese cities are being encircled by untreated sludge – a pungent, viscous mixture of human excreta and stormwater runoff. Four years ago in Beijing, trucks loaded with untreated sludge from the city’s largest wastewater treatment plant were illegally dumping mountains of sludge in the outskirts of the capital as “free fertiliser” for peri-urban farms. Similarly, in the southern China city of Guangzhou, disposing toxic sludge into the nearby river required nothing more than a hired boat. From the far western desert city of Urumqi to the eastern metropolis of Shanghai, more and more of China’s cities are struggling to manage mountains of sludge and municipal waste, as well as floods of wastewater and stormwater runoff.

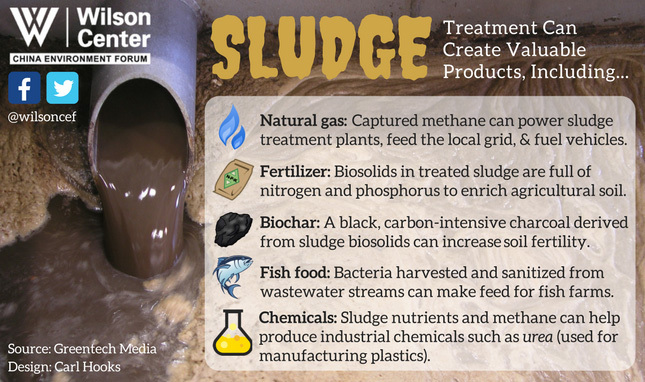

Many Chinese cities dump their sludge into landfills with minimal treatment (or none at all) instead of tapping its hidden energy reserves and turning it into rich compost. Although more than 80% of the sludge currently receives primary dewatering in treatment plants, at least 75% of the dewatered sludge does not undergo any further forms of treatment. When it decomposes, untreated sludge produces methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than CO2 when released into the atmosphere. China’s 2015 Water Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan prioritises ending irresponsible disposal, as well as harnessing methane and nutrients from sludge at wastewater treatment plants. Xiangyang, a city in Hubei province, has built one of the few plants in China that consistently generates biogas from waste. The plant captures more than 12,000 cubic metres of methane per day and processes it into compressed natural gas that fuels local taxis and trucks.

But exploiting the energy potential of sludge has never been easy in Chinese cities. Excessive stormwater runoff in Chinese cities dilutes wastewater, so treated sludge has low amounts of organic matter and consequently produces a limited amount of methane, thereby making biogas production an infeasible option. China’s Ministry of Agriculture has banned the application of treated urban sludge on crops, in part because industrial wastewater (potentially up to 30%) is sometimes mixed into municipal treatment, which could create toxic residues on dried sludge if not sufficiently treated.

Poop-to-power

Eight massive, ovular steel digesters gleam under the sun in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighbourhood. At the borough’s Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant, these digester “eggs” use anaerobic digestion to treat millions of gallons of black sludge flowing through 180 miles of New York City (NYC) sewers. By removing oxygen and heating the sludge to about 98 degrees Fahrenheit for 15 to 20 days, bacteria inside the digesters produce biogas composed of methane gas and CO2. Forty percent of that methane is reused in boilers to sustainably heat the plant and its digesters; the excess 60% is siphoned and purified on site into pipeline-quality renewable natural gas by National Grid, a British utility company operating in New England.

Since 2013, the novel public-private partnership between the NYC Department of Environmental Protection and National Grid has made Newtown Creek one of the country’s standout wastewater treatment plants. The plant treats up to 330 million gallons of wastewater per day – close to a third of what New York produces daily. A 53-acre facility serving upwards of 1.3 million people, Newtown Creek remains the largest of 14 such plants in NYC.

Around 250 tons of food waste are fed into the digesters each day

In 2013, NYC Waste Management began delivering food scraps, spoiled food, and food-soiled paper collected from city schools and restaurants to Newtown Creek. Around 250 tonnes of food waste are fed into the digesters each day, which enriches the bacteria and organic matter in the sludge and brings it to levels that enable Newtown Creek to churn out 500 million-plus cubic feet of methane annually. Co-digesting food scraps with sludge is so productive that a 2013 NYC law requires the city’s 350 largest food waste-generators to send their waste to anaerobic digesters (or compost), rather than landfills or incinerators.

The dynamic duo of co-digestion and methane capture allows Newtown Creek to sustainably power its operations, produce enough renewable natural gas to heat 5,200 local homes, and reduce NYC’s annual greenhouse gas emissions by 19,000 tonnes – the equivalent of taking 1,900 cars off city streets, at no cost to Brooklyn taxpayers. The facility demonstrates how cities can utilise public-private partnerships to transform noxious waste into a green energy resource.

Borrowing from Brooklyn?

Is Newtown Creek a “model plant” for Chinese cities to emulate? “Not completely,” says Kartik Chandran, a Columbia University professor and 2015 MacArthur “Genius” Award winner who specialises in sludge-to-energy engineering. Chandran and his research team have been studying the microbial processes inside Newtown Creek’s digesters and 19 other systems around the world. “There are actually far more advanced projects [than Newtown Creek] in the United States,” he told the China Environment Forum in a recent interview, including those in Honolulu and Oakland.

Anything organic is game

If China hopes to upgrade cities’ sludge-to-energy capacity, then using food waste and other organic material is crucial. The way to produce more energy-intensive methane from sludge is by feeding digesters with food waste; as Chandran notes, “anything organic is game.” Chandran’s research shows that Newtown Creek’s digesters are not yet swallowing food scraps at full capacity. Therefore, “the biogas Newtown Creek produces is diluted. It is 50-60%methane and not a high-quality energy source compared to more concentrated biofuels.”

Furthermore, the anaerobic digestion process at Newtown Creek converts only the carbon in sludge to methane. A more efficient “win-win” would be to also recover the nitrogen and phosphorus from sludge, since these two nutrients can help produce agricultural fertiliser or industrial chemicals. But strict state regulations on nutrient removal limit these additional outputs at New York’s plants, a problem facing China and other developing nations as well.

Government guidelines can also prevent wastewater treatment plants from exploiting the biosolids or completely capturing methane during co-digestion. Ambitious Chinese cities such as Beijing “are going to build digesters, but have to find ways to reduce methane emissions and use it for energy,” said Chandran. “I don’t think the regulatory framework has been thought out.”

In 2015, Beijing treated 23% of its sludge until it could be disposed of safely. Only a handful of wastewater treatment plants are capable of enhanced sludge treatment. Many of the 3,916 municipal wastewater treatment plants in China have installed some methane capture technologies, but to date only around 50 are attempting to use captured methane for energy, while many others flare it.

Constructing modern sludge-to-energy plants may be neither quick nor cheap

In addition, constructing modern sludge-to-energy plants may be neither quick nor cheap. Newtown Creek was built in 1967, and desperately needed an upgrade by the early 2000s. To expand the plant’s capacity and comply with federal standards set by the Clean Water Act, the New York City government poured US$680 million into renovating it between 2003 and 2009. To complete the redesigns, NYC Department of Environmental Protection contracted with private architectural, design, and engineering firms and even formed a citizens committee to represent neighbourhood interests.

Before they negotiate public-private partnerships or invest millions into building and renovating sludge-to-energy plants, Chinese municipalities should be aware of the technical and policy problems at Brooklyn’s plant. Newtown Creek’s unique shortcomings – not merely its best practices – can inform sludge treatment in China, making it a doubly valuable case study for city officials.

This article was first published on the New Security Beat blog of the Wilson Center. It is the first in a series of case studies of innovative wastewater treatment plants in Brooklyn and Brazil from the China Environment Forum and Circle of Blue’s Choke Point China Initiative.