Each year, the winter chill creates a rift between China’s north and south based on radically different policies when it comes to heating, and with consequences for air pollution and life expectancy.

In the 1950s, premier Zhou Enlai drew a line across the country following the River Huai and the Qinling mountains. North of the line, temperatures in January fall below zero degrees whereas in the south temperatures remain above freezing. This difference led the government to provide district heating in the north, which relies on centralised coal-fired boilers to provide free or heavily subsidised heat. In the south, no district heating was provided.

Over half a century later this system remains in place. It means that hundreds of millions of residents in northern China enjoy reliable and affordable heating, while those in the south depend on air conditioning units, electric heaters, and blankets to make it through winter – and get no subsidies. For some people, the provision of heating is a consideration when choosing where to live.

But northerners are paying for their warmer winters with their health, according to research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The toll

According to the study, burning coal to power district heating produces air pollution that is harmful to human health, with the average life expectancy in the north 3.1 years shorter than in the south.

The research was carried out jointly by academics from the US, Israel and Hong Kong and involved a quantitative analysis of the link between life expectancy and inhalation of particulate matter – with the north-south difference in heating policy the variable studied.

The researchers looked at the causes of death regionally from 2004 to 2012, recorded in China’s national disease monitoring database. They then analysed it in combination with air pollution data going back to the 1980s.

They found that local heating policies have a major impact on the levels of tiny particles (PM10) in the air. Long-term exposure to PM10 increases the incidence of heart and respiratory diseases and reduces expected lifespan.

The research found a steep increase in air pollution moving from the south of the country to the north. People in areas that benefit from heating subsidies see PM10 levels raised by 41.7 micrograms per cubic metre, on average. This contributes to a reduction in lifespan of 3.1 years and a 37% greater incidence of death from heart disease and stroke.

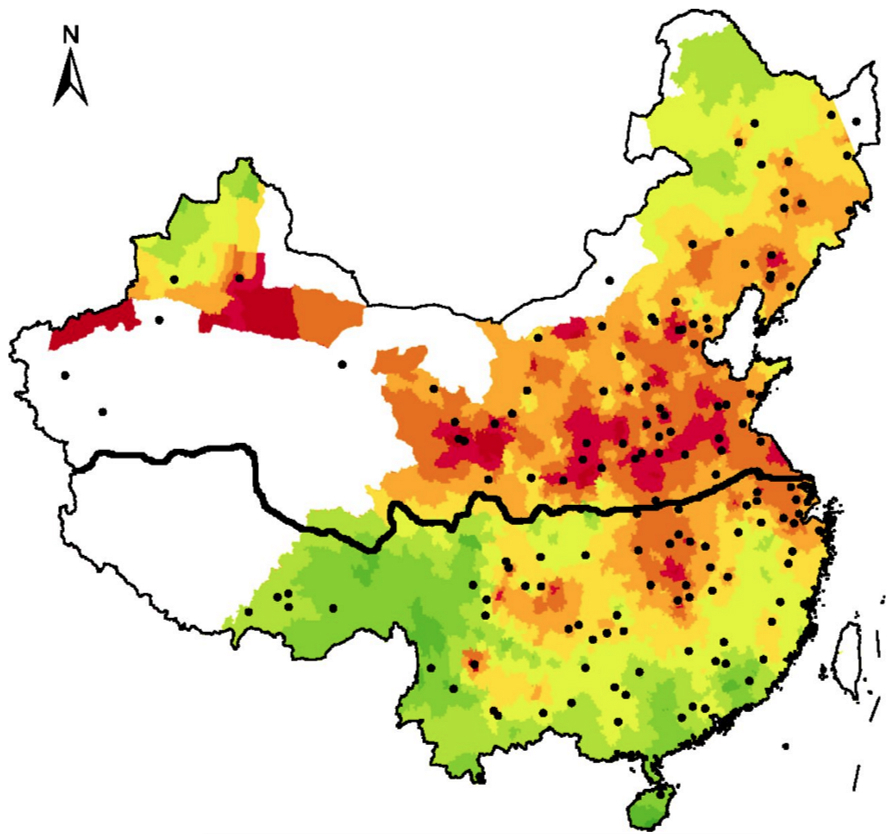

Air pollution map of China

Key: Green, yellow and red marking low, medium and high levels of PM10 pollution, respectively.

Source: Ebenstein, Avraham, et al. "New evidence on the impact of sustained exposure to air pollution on life expectancy from China’s Huai River Policy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2017)

Energy reform heats up

He Guojun, assistant professor at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and one of the report authors, says the research is not a criticism of the heating policy itself, nor is it calling for it to be abolished.

The paper does not offer any specific policy suggestions. But He Guojun said that to reduce air pollution many cities have switched to using natural gas or electricity to power homes and other buildings instead of burning coal. This approach can deliver enormous long-term health and welfare benefits.

“It’s not the case that you have to choose between heating and clean air,” he stressed.

The government has been working to reform heating provision in recent years, in line with wider efforts to curb air pollution from industry. The implementation of the 2013-2017 Air Pollution Action Plan means that some factory operations are either stopped or restricted during peak pollution months .

In September, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Finance and the National Energy Administration published guidance on cleaner heating provision for 13 provincial-level governments. It required changes by winter, including the preferential use of electricity or natural gas over coal, according to local availability.

A switch to electric heating in homes requires new heaters to be installed, and in some cases upgrades to the electricity grid. This is costly and complicated so most changes have seen natural gas used to replace coal-fired heating instead.

In 2017, almost all heating provision in central Beijing was gas-powered. This switch has saved 9.2 million tonnes of coal being burned, according to official sources. Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong, Henan and Shaanxi provinces are also working to switch from coal to gas as quickly as possible.

According to a report from China Environmental News, natural gas produces 90% less particulate matter and nitrogen oxides compared to the same weight of coal. In Beijing – China’s first city to switch from coal to gas heating – PM2.5 and PM10 levels for November are down 55% and 46%, respectively, from last year.

However, these rapid changes have put pressure on energy supplies. According to the same report, last year’s consumption of 198.2 billion cubic metres of natural gas is expected to rise 17% this year. News platform Xinhua reported that Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong, Henan and Shaanxi provinces have all seen natural gas shortages and price spikes this year.

The rapid switch in fuel has led some industry insiders to question whether domestic production and imports of natural gas can grow quickly enough to meet demand.

Already, the Ministry of Environmental Protection was forced to lift a ban on coal-fuelled heating systems in areas that are yet to transition or had inadequate supplies of natural gas but which were left without heating in freezing temperatures.

The government’s long-term plans predict natural gas consumption to rise from 198.2 to 600 billion cubic metres by 2030. Half of that is expected to be met by imports.

Gas consumption will rise from 198.2 to 600 billion cubic metres in 2030, with half of that coming from imports.

Zou Ji, president of the Energy Foundation’s Beijing office, said at a seminar on air pollution on November 29 that experiences in other countries showed a reliance on natural gas is inevitable, and that it would be extremely difficult for China to avoid this.

Liu Youbing, an official at the Ministry of Environmental Protection, told a press conference that the switch from coal to gas had proved an effective way of reducing air pollution.

A coal-dominated energy mix is a major cause of China’s air pollution, Liu added, stressing that ongoing reforms were essential to tackling air pollution.