Public health campaigns have been telling people for years to apply a generous layer of sunscreen when they go to the beach, and to make sure they’re fully protected before getting into the water. But recent research from Hong Kong Baptist University finds that sunscreens are also having a shocking effect under the surface by causing deformities in fish embryos.

Few people have heard of chemicals commonly used in sunscreens, such as benzophenone-3 (BP-3), ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate (EHMC) and octocrylene (OC). When they are applied to the skin they block ultraviolet radiation, but in the water they also cause abnormalities in the young of zebrafish, and accumulate in the food chain where they can ultimately reach the human body.

The authors of the paper, which was published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, have called for regulations to cover the use of such chemicals in personal care products.

Pollutants concealed in everyday products aren’t as noticeable as smog or foul-smelling waterways and the damage they cause isn’t immediately visible. But China is already the world’s largest manufacturer of chemicals and neither regulators nor the public know much about the tens of thousands of different substances being transported and used around the country.

Meanwhile, the use of the chemicals is causing a rise in environmental health issues. Experts say that systems designed to deal with visible pollution and accidental releases aren’t well-suited for managing hidden pollution, and urgent changes are needed to address this.

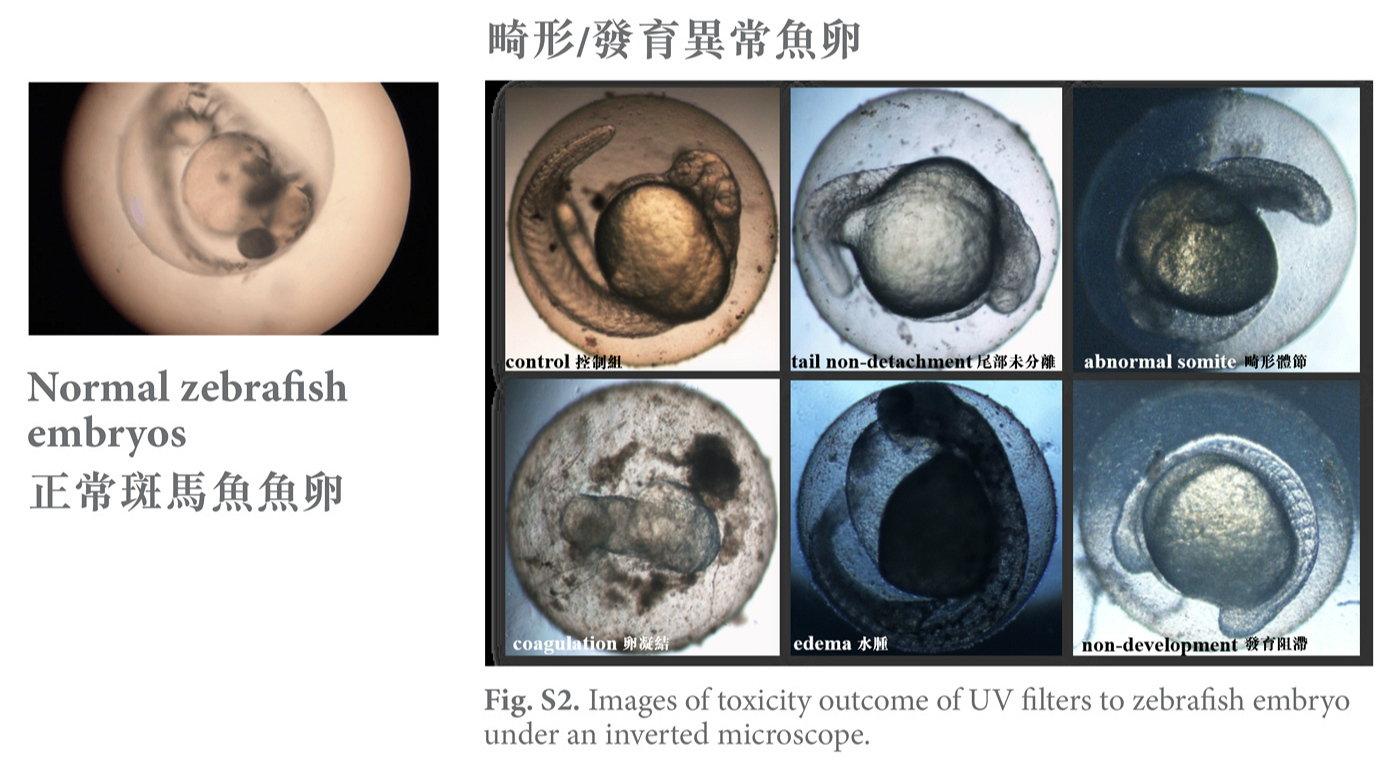

Abnormal zebrafish embryos, from Li, Adela Jing, et al. "Joint Effects of Multiple UV Filters on Zebrafish Embryo Development" Environmental Science & Technology 52.16 (2018)

Abnormal zebrafish embryos, from Li, Adela Jing, et al. "Joint Effects of Multiple UV Filters on Zebrafish Embryo Development" Environmental Science & Technology 52.16 (2018)

Seeing the danger

In recent years, China has strengthened its system of environmental management and seen some impressive results. PM2.5 levels in Beijing in 2017 were 35% lower than in 2013 following a three-year action plan that was initially regarded as next to impossible to achieve. The 2015 Environmental Protection Law and the Party leadership’s focus on “ecological civilization” have also empowered regulators to impose heavy fines on polluting firms and even shut down factories and jail offenders.

Visible pollution is being brought under control, but hidden pollution is still mostly unregulated.

There are about 45,000 chemicals known to be in circulation on the Chinese market (the actual number may be much larger), but fewer than 3,000 are regulated. These include substances that present clear risks because they are explosive, flammable or highly toxic. However, Greenpeace has calculated that about half of the 45,000 chemicals could cause long-term harm to the environment or human health.

“China’s management of chemicals focuses on those which are dangerous and present definite and immediate risks,” explained Wang Yan, toxics campaigner at Greenpeace. “Management of chemicals which have slower harmful effects on health and the environment is weaker, particularly when it comes to transportation, processing and use, and release into the environment.”

Wang added that China’s emphasis is on workplace safety and the prevention of accidents, with less thought given to people’s health and protection of the environment. For example, the BP-3 found in sunscreen was identified as a potential endocrine disruptor as early as 2012. Its use in cosmetic products is restricted by EU regulation. But BP-3, like many other similar chemicals, is not regulated in China.

Liu Jianguo, associate professor at Peking University’s College of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, has written that dangerous and polluting production methods and use of chemicals have shifted from developed to developing nations, such as China, where technology and regulations are less developed.

Regulatory blind spots

Experts interviewed by chinadialogue said that China faces a growing challenge to manage chemical risks in an environmentally safe way and that current measures are inadequate. One problem is that environmental regulators are focused on more visible issues, such as smog and water pollution, and give little priority to hidden risks.

Ma Jun, director of the Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs, added that “environmental law enforcement agencies are facing multiple challenges with limited resources”.

China has no national law on the management of chemicals. The highest-level relevant rules are the Regulations on the Safety Administration of Dangerous Chemicals, revised in 2011 by the State Administration of Work Safety (now the Ministry of Emergency Management). These regulate about 3,000 substances, which are included on a register of dangerous chemicals. The regulations were developed from a 1987 set which had been in place for 20 years and covered mainly explosive, flammable and highly toxic substances.

The aftermath of the 2015 chemical warehouse explosion in Tianjin. Management of chemicals in China has long focused on preventing incidents like this, with less attention paid to public health and the environment (Image: Wu Hao/Greenpeace)

The aftermath of the 2015 chemical warehouse explosion in Tianjin. Management of chemicals in China has long focused on preventing incidents like this, with less attention paid to public health and the environment (Image: Wu Hao/Greenpeace)

The 2011 revision added “harmful to the environment” to the definition of dangerous chemicals, which allowed the regulation of chemicals for environmental reasons. The Ministry of Environmental Protection then published a trial method for registering chemicals hazardous to the environment in 2012, including those representing persistent and bioaccumulative risks. It included extra regulations for 84 environmentally-harmful substances and required firms manufacturing and using the chemicals to register and submit annual reports of releases and transfers.

Unfortunately, these departmental regulations were not enforced properly, and in 2016 they were annulled – a rare surrender for China’s environmental regulators. Industry media outlet REACH24h said at the time that “the Ministry of Environmental Protection held a number of seminars and training sessions to encourage implementation, but with industry resistance and a lack of supporting documents, the regulations could not be maintained”.

Wang Yan said that “environmental management of chemicals is marginalised, both within the environmental regulatory system and that for chemicals”.

A worsening health crisis

With effective regulation still not in place, environmental health issues are becoming more apparent. A report from the China National Cancer Centre, China’s Cancer Burden, published this year, shows that the most common cancer among women is breast cancer; incidences between 2000 and 2013 grew by 3.5% annually – the highest rate of growth globally. Rates in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou are approaching those in the developed world.

In the most recent evaluation of endocrine-disrupting chemicals from the World Health Organisation and UN Environment Programme, a worldwide increase in incidence of some diseases is attributed partially to “unidentified environmental factors”. These include cancers of the endocrine system, such as breast and testicular cancer, reproductive diseases and infertility. The report also noted that “chemicals to which all humans in industrialized areas are exposed have been shown to interfere with hormone synthesis, action or metabolism”.

A different regulatory approach

China’s environmental regulators have wanted to bring chemicals under their jurisdiction for a long time. The first attempt to establish an actively maintained list of chemicals, including those representing persistent and bioaccumulative risks, and require those manufacturing and using the chemicals to register and submit annual reports of releases and transfers, resulted in failure. However, it was regarded as an embryonic form of a pollutant release and transfer registry, a key part of any system for managing environmentally-harmful chemicals and encouraging firms to use less or opt for alternatives. The US Toxic Release Inventory and the EU’s Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (PRTR) both improved the management of toxic and harmful chemicals in those jurisdictions.

According to Ma Jun, “International experience shows that a PRTR system allows the media, environmental groups and the public to use openly available information to pressure firms into cutting emissions, and can give the government a more comprehensive and accurate grasp of how firms are releasing and transferring harmful chemicals”.

After the above mentioned regulation was abandoned, policy-makers lowered their ambition and no longer aimed to create a complete regulatory system all at once. A source close to policy-makers said that “merging regulation of chemicals with governance of water, soil and air is a more realistic direction at the moment”.

In 2017 the then Ministry of Environmental Protection published an initial list of chemicals to be prioritised for regulation that included 22 persistent organic pollutants and endocrine-disrupting chemicals. The change resulted from powers granted by a State Council action plan on water pollution, and required licenses to release the substances in waste water, limits on their use in products, and encouragement to switch to alternatives.

In June the Communist Party Central Committee clarified the direction on soil pollution, saying that the risks associated with harmful chemicals in the environment should be assessed, with strict restrictions on the manufacture, use and import of high-risk chemicals, which should be gradually eliminated and replaced. This new authority will be a further boost to management of environmentally-harmful chemicals.

But industry insiders say that dividing management across air, water and soil is only a short term measure. “This will make both regulation and public oversight more difficult,” said Ma Jun.

The creation in March of a Ministry of Ecology and Environment from the old Ministry of Environmental Protection is cause for optimism though. According to leaked reports, the ministry is actively working on a new set of regulations based on the principles of “risk prevention and control at the source”. They will classify harms, assess risks and manage chemicals by banning, restricting or controlling their use.

This is the first in a series of chinadialogue articles on the environmental regulation of chemicals in China. We are grateful to the Swedish Chemicals Agency for its support.

![The sea ice and mountains in Spitsbergen, Svalbard during the Arctic summer [Image by: Josh Harrison/Alamy]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2018/11/arctic-summer-sea-ice-300x200.jpg)