China is currently facing the biggest wave of migration to cities ever seen in human history. The government plans to increase urbanisation from its current rate of 55% to the 70-80%, the typical level of developed countries.

This means that China will have 300 million additional urban residents within the next 15 years – the equivalent of the entire population of the US. These new city-dwellers hope to find higher wages and an improved quality of life, but the shift will also lead to higher energy consumption.

“Urbanisation is China’s greatest economic growth point,” China’s premier Li Keqiang has stated. But according to energy and climate researchers, it also poses challenges as cities struggle to meet the needs of this new demographic.

Developing green, low carbon cities has long been a major pillar of China’s climate change strategy. In 2010, 42 low carbon pilots were set up by the National Development and Reform Committee (NDRC), 36 of which were cities.

The architects of this latest phase of low carbon development schemes will need to carefully evaluate the results of earlier phases.

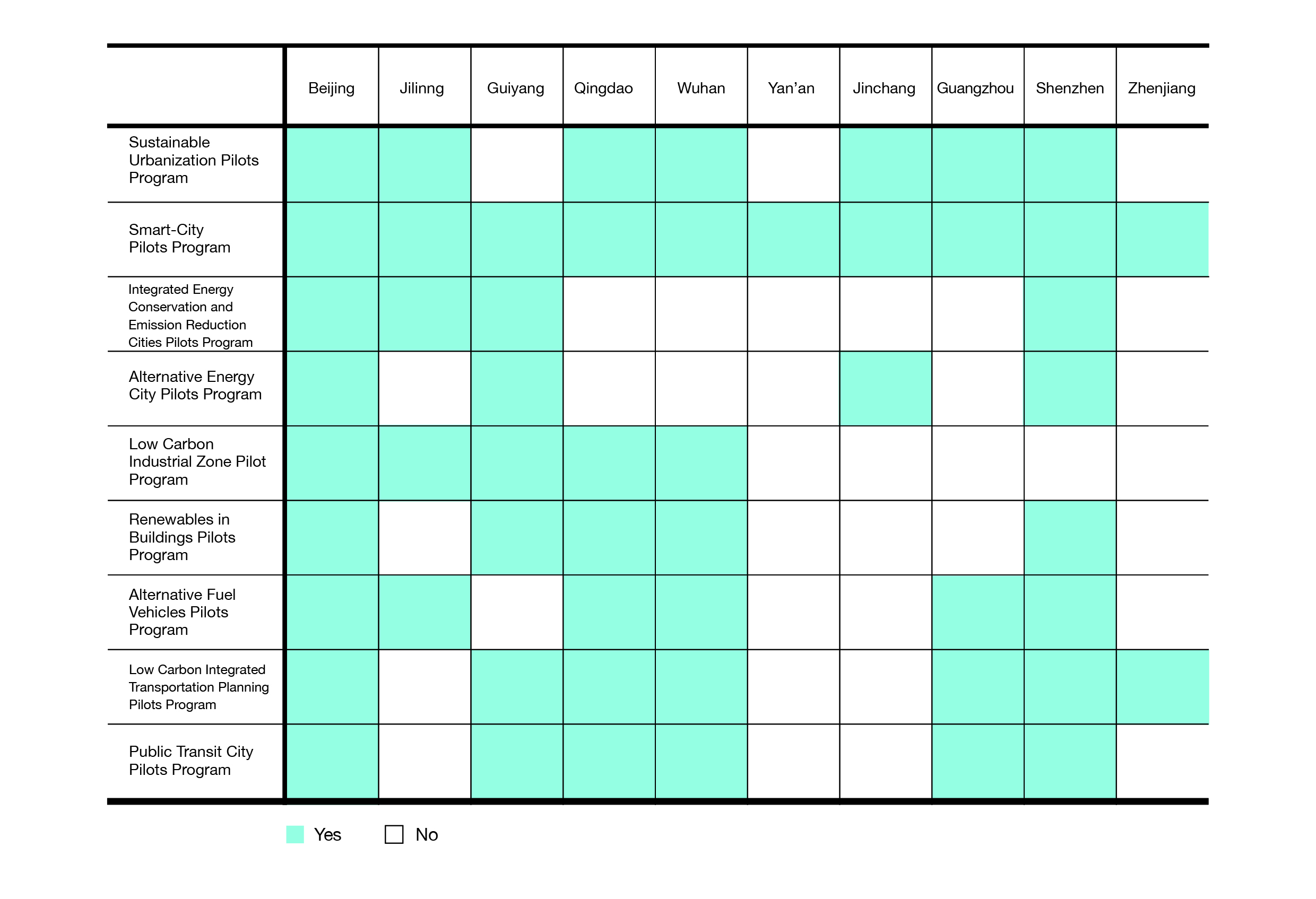

The selected cities include Shanghai on the eastern coats; Jinchang, a resource-rich but underdeveloped city in the west; Shenzhen, a special economic zone north of Hong Kong; and Yanan, in central China.

As well as geographical variations, there are differences in carbon emissions output and size of GDP between these cities.

For example, the emissions of Jinchang and Jiyuan are several times higher than those of Wenzhou and Guilin. In economically developed Shenzhen, Suzhou and Guangzhou, per capita GDP is US$10,000 per year, compared to US$2,000 in Guangyan and Ganzhou.

The short-term goal of these pilot schemes is to achieve lower GHGs relative to each city’s local average.

The race for peak emissions

The short-term goal of China’s low carbon city pilots is to achieve low carbon in relative rather than absolute terms. A very different measurement index is used to those from cities in developed countries. These Chinese cities are still in a period of rapid economic growth, and there is bound to be a large spike in greenhouse gas emissions over the next decade. The carbon emissions from these cities are also characteristically very different to those from developed countries.

The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s China Energy Group predicts that industrial emissions from these cities will surpass those of the surrounding area by more than half again. Carbon emissions from the transport and construction sectors are still comparatively low, but are bound to rise along with living standards.

The aim of the pilot programme is to establish a model for economic growth with reduced carbon emissions. To do this, it will focus on cutting carbon intensity (carbon dioxide emissions per unit GDP). The volume of carbon emissions, therefore, is used only as a reference index.

The work of pilot schemes started with education in the basics, for example, teaching local officials the difference between carbon and charcoal.

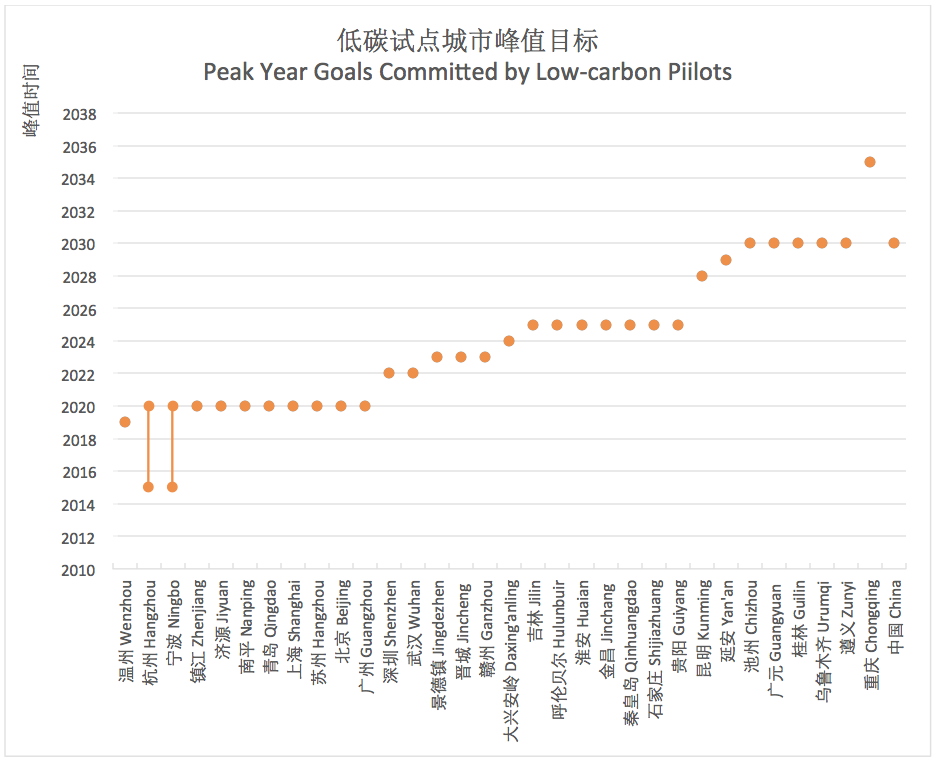

Each pilot city has proposed a reduced carbon intensity goal for 2020 to fall in line with or even exceed the upper limit of the national goal, which is a decrease of 40-45% from the 2005 carbon intensity level. A total of 27 cities have proposed to meet their peak emissions targets before 2030.

As part of these efforts, a nine-city strong group, the Alliance of Peaking Pioneer Cities, was formed at the China-US Climate Leaders Summit last September. Zhenjiang was among the cities that declared a target to meet peak carbon emissions targets ten years before the national goal.

Most of the cities have followed the same action plan, with some small variations. The focus has generally been on energy saving in the industrial sector, with an effort to control emissions increases within construction, farming and forestry.

The goals have factored in regional differences, such as access to resources. There are also clear differences in the implementation policies, with some cities emerging as models for state policy in other sectors – as eco-city pilots, new energy model cities, low carbon transport pilots, comprehensive energy saving and emissions reduction pilots, and so on.

New innovations

The best innovations have emerged at the project level. Notable examples include: Hangzhou’s public bicycle hire system (which was recognised as one of the eight best in the world in a vote conducted by the BBC); as well as Beijing’s regulation of real estate construction, Zhenjiang’s carbon platform, and Shenzhen’s green building developments.

Since operations began in 2008, a total of 135,000 kilometres has been travelled by bike in Hangzhou. This translates into savings of 4.61 tonnes of standard coal and 122,107 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, when compared to the fuel needed to travel by bus over the same distance. Compared with cars, the savings amount to 184,975 tonnes of standard coal and 490,424 tonnes of carbon dioxide.

In Zhenjiang, local authorities have created China’s first city-level carbon emissions assessment and management platform. In Beijing, where there has been great pressure to regulate the industrial sector, energy consumption per unit of industrial added value fell below 35% during 2011–2015, a level well below the national target.

During this period, Beijing economy continued to grow by an average of 7.7%, with local revenue increasing by over 10%, proving that carbon reductions do not have to come at the cost of GDP growth.

Shenzhen now boasts the largest scale and concentration of green buildings in China. The city’s Jianke Office Building, its landmark project, uses 40-70% of the electricity of an average office. Each year this will reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 1,471 tonnes, a 58% reduction from those of average buildings, while the construction cost is only 60-70% of averaging buildings.

While it is still too early to measure the total effect that these low carbon cities have had on China’s emissions, it appears that many will meet their carbon intensity targets ahead of schedule.

Challenges and opportunities

China’s cities must contend with the legacy of environmentally damaging industrial growth.

Baoding in Hebei province, for example, has previously ranked as number one on the list of most polluted cities. Transitioning into the next phase of its development will not be easy.

The biggest contribution of the pilot scheme has perhaps been to establish a mechanism by which to roll out future programmes.

Environmental management systems and carbon emissions inventories have been set up from scratch and environmental research institutes have more capacity, in some regions. Meanwhile, carbon markets and carbon financing are gradually becoming integrated into the mainstream economy.

These pilot cities will become a key part of this global pledge to tackle climate change enshrined in the Paris Agreement.