Yan was luckier than many of his classmates. After graduating in 2014 he found a steady job in his hometown in Shanxi province, Datong, as a technician at the Tashan Solar Power Farm run by the Datong Coal Group.

Solar was a new sector for Datong Coal and the Tashan project aimed to produce 20 megawatts of electricity. Within a year it had connected to the grid (it currently generates 10MW).

While Tashan can’t compete with nearby coal-fired power plants in terms of output, new government subsidies have made the price of energy for consumers more competitive. Solar power can be sold to the grid for a higher premium, which makes projects like Tashan attractive for investors. On average, coal power fetched 0.30 yuan (US$0.04) per kilowatt hour (KWh), versus solar power at 1 yuan.

Tashan has grown since Yan joined and now employs 10 regular workers. It’s not well paid, he says, but it’s easy work that provides job security (solar plants this size can have a lifespan of 25 years).

Yet, Tashan remains an anomaly in an economy dominated by heavy industry. Large concrete factories loom in the distance, beyond which lie vast aggregate quarries (an essential ingredient in concrete) for mine roads. Yan says you can feel the buildings shake when the miners are blasting the stone.

Coal legacy

Coal-mining on a large scale started in Datong early in the 20th century. Industrial development during China’s reform period in the 1980s and 1990s meant increased demand for coal (still the country’s primary source of energy), and rapid GDP growth for Datong.

However, when coal consumption started to fall nationally in 2013, concern among coal workers spread as jobs became scarce. Where once Yan’s friends could count on a job for life, nowadays more of them are turning to non-industrial jobs, such as retail.

Despite the threat to jobs, China’s decisive shift toward low-carbon development means Datong must find a clean energy alternatives to coal.

Solar in Datong

In 2014 the city published a “Low-Carbon Action Plan”. It said that by 2020, 15% of primary energy would be drawn from non-fossil fuel sources (up from 1% in 2005); while carbon intensity would drop by 45% from 2005 levels.

For Datong, non-fossil fuel energy means wind and solar. On the north of the Loess Plateau there is little vegetation or precipitation. It does, however, receive over 3,000 hours of sun a year (over eight hours a day on average).This makes it one of China’s most solar-abundant regions.

Non-mining areas to the north of the city are already home to many wind farms. In the south subsidence from mining has spoiled the land, which is useless to farmers, but can be still be used to build solar plants.

In 2015 the city became home to a “frontrunner” solar farm built on a subsidence zone and will expand. Now, up to 3 gigawatts of solar power capacity is planned to be built by 2019 (installed capacity that is around three times the average size of one nuclear reactor) with tendering for the first round of 1 gigawatts of capacity starting last June. The State Power Investment Corporation, China General Nuclear and Three Gorges New Energy are the main contractors.

At a road junction south of Datong, where a solar plant will join a cluster of traditional energy sources including coal and nuclear. Photo: Liu Yuyang.

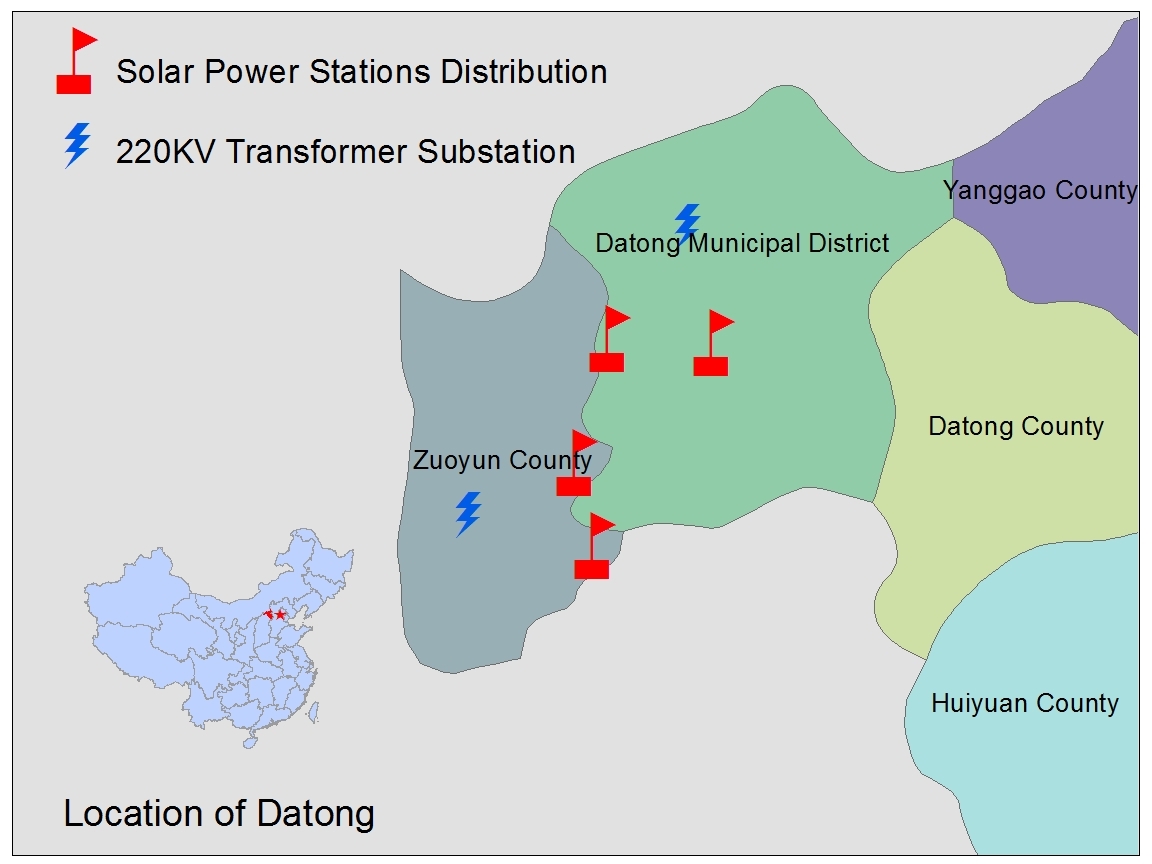

On March 31 the Shanxi Development and Reform Commission approved plans for use of electricity from the frontrunner project, which envisages that 500 megawatts of power further off to the north-west of the city will be collected and delivered to the 220 kilovolt Nanjingzhuang substation; while another 500 megawatts generated nearer the city will be sent to a 220 kilovolt substation to Datong’s north. This way electricity generated near Datong can supply Beijing.

More solar plants are being built in Datong on former coal mines in other parts of Shanxi. As of February this year, Shanxi had 70 gigawatts of power generation capacity, ranking eighth among China’s provinces. Coal-fired power now accounts for 88% of that figure, down from about 93% in 2010.

Out of the mines

For years Datong has been trying to reduce its reliance on coal. According to figures from the provincial environmental authorities, China’s “coal capital” enjoyed the best air quality in Shanxi last year, and maintained that performance into the first quarter of 2016. Wider use of solar and wind power will further reduce air pollution and carbon emissions associated with coal use.

But for most locals, the benefits of solar power aren’t as obvious as those of coal. For now, at least, solar power is failing to provide enough jobs.

Datong in March is still clad in a grey winter sky. At the entrance to Liuguanzuang village in the south of the city, construction of a JA Solar 500 megawatt facility is proceeding at pace, and must be finished before the rainy season starts in June.

Jobs losses

Solar power plants don’t take long to build and if everything goes smoothly this one will take three months. Nor is it very labour-intensive. The foreman, Wu, employs his own team of 30 or 40, supplemented by a dozen or so locals.

Locals (who are paid per panel installed) have less expertise than specialist contractors, so make slower progress. They earn 100 yuan a day on average.

“Locals would work for just 50 yuan a day. They’ve moved into new homes where they need to pay for utilities and food and so on, and they’ve got nothing else to do,” said Wu.

A huge seam of coal (1,800 square kilometres wide, and 30-40 metres deep) lies under Datong. But years of coal mining has led to subsidence, rendering many parts of the city’s environs no-go areas.

Since 2006 tens of thousands of miners and locals have been relocated from those areas to housing in Heng’an New District, on the same road as the Tongmei Coal Group headquarters. In May this year the city government came up with a relocation plan that will see 19,000 people in 8,000 households move from subsidence areas.

Liu is 60 years old and one of Wu’s local workers, but has to travel from a mountain village 60 kilometres from the worksite.

When he was younger, Liu worked at a small mine earning a daily rate for bringing coal up a shaft. Money was always available if you were willing to work. At 45, Liu began working on the surface, still making a 100 yuan or so a day. But several years ago the mine went bankrupt, forcing Liu to travel further afield for work.

Liu’s village is the only human habitation in a huge radius around the site. Now he travels an hour to work each day along a bumpy and potholed road on a minibus he shares with other workers.

The driver also works at the mine, setting off at 7am and getting home at 10pm. Once hundreds lived here, the remaining 40 or 50 are mostly old or infirm who scratch a living by subsistence farming and doing casual labour.

Liu’s son is working to the north of Datong, while his daughter, whom he cares for, is seriously ill.

“It costs 7,000 yuan a day to stay in hospital, we couldn’t afford it,” says Liu. Her son is in fifth grade at the township school, and every Friday Liu makes the 40 minute motorbike trip to pick him up, takes him back on the following Monday.

Every spring Liu and his wife plant their 20 mu of land with millet and wheat, then hope the rain gods are kind. In a good year they can sell the harvest for over 5,000 yuan, of which over 3,000 yuan is profit.

Puffing on a pipe, Liu sits cross-legged on the family’s heated bed, talking about the future: “I’ve been working at the site for five or six days. If I can make 100 yuan day I’ll keep working there, otherwise I’ll have to think of something else.”

Those who still have permanent jobs with mining companies might have stable work, but with reductions in output and large scale reallocations in pursuit of alternative work, they are also worried. Anyone over 50 years of age at least has the reassurance of a pension to look forward to. But those who are slightly younger than that threshold don’t know what other work they can do.

So how can low-carbon development also be sustainable?

The permanent population of Datong is 3.4 million, while according to the Tongmei Coal Group website, the company employs 200,000 people. Coal fuels this city’s economy, ensuring that an energy transition is also an economic transition. It is not as simple as replacing coal with wind or solar – new sources of economic growth are also needed.

In an effort to maintain growth while reducing carbon emissions, former mayor Geng Yanbo once tried to boost tourism by restoring Datong’s historical heritage.

The city walls by night. Image: Liu Yuyang

The period 2008 to 2012 saw the much of old city rebuilt, with 7.4 kilometres of Ming dynasty city walls reconstructed, featuring replica watchtowers every hundred metres. The city was transformed, restored to its original grandeur. This was the capital of the Northern Wei dynasty and a strategic border defence for later dynasties, and boasts the Yungang grottoes, a world heritage site, and many national historic sites. There is a real potential for tourism here.

But the energy transition is still critically important to long-term development. Once coal exports have declined, electricity exports will become a major source of income. That means generating capacity needs to be kept up while coal use falls. So how to both develop solar power and increase added value is key to local development.

And currently, the best partner for solar power is agriculture.

This new double act has started to gain popularity in China during the last two years, and Shanxi is no exception. A 30 megawatt combined solar-agriculture project was completed in July last year in Shou county and is now hooked up to the grid, while this April, China’s biggest such arrangement, a 50 megawatt solar greenhouse project in Changzhi, was also completed and connected.

This year, “Datong will see construction of solar power stations (including solar-agricultural facilities) of 692 megawatts of installed capacity in total, with solar-agricultural units ranging from 10 megawatts to 50 megawatts”.

Perhaps one day Liu’s village will have solar-agricultural facilities. Liu and other former miners could work in their own greenhouses, no longer travelling long distances for short-term work.

Those interviewed requested that their names be changed for the purposes of this article

![Tubewell spouting water. Excessive use of groundwater for agriculture is creating a crisis [image by Shahzada Irfan]](https://dialogue.earth/content/uploads/2016/06/Tubewell-300x225.jpg)