China’s Soil Pollution Prevention Action Plan, which was released late last month after years of delays, sets out clear goals in terms of dealing with soil pollution, but a lack of detail in the document has disappointed environmental experts and campaigners.

The plan, which has been three years in the making, mandates that a worsening of soil pollution will be brought under initial control by 2020; and that soil quality nationwide will be stabilised or improve by 2030.

By the middle of the century, China’s soil would be required to show an overall improvement. By the end of this decade, 90% of China’s polluted land (including arable land and other types) must be made safe to use, with that figure required to rise to 95% by 2030.

Chen Nengchang, a researcher at the Guangdong Institute of Eco-environment and Soil Sciences, told chinadialogue that there are no problems with the overall approach of the plan, such as the establishment of a soil pollution monitoring network, a categorisation of agricultural land by degree of pollution, and better protection of unpolluted land.

But a lack of clarity means it will be hard to match up the overall targets with specific actions, or to judge from the text alone if those targets will be met.

Chen said that there are no explanations of what standards will be used to evaluate levels of pollution, what “safe to use” actually means, and whether or not the plan alone will be enough to reach that 90% target.

Overall, experts have expressed disappointment with the long-awaited soil pollution plan.

See also: China’s tainted soil initiative lacks pay plan

The biggest problem that local government, companies and the general public face is that it is currently unclear how bad China’s soil pollution really is.

How much land is polluted? Where? How much polluted land is now “safe to use”? This information has not been made public, therefore Chen cannot say how much work is needed and how difficult the process will be.

And that lack of disclosure is the reason tackling soil pollution in China has taken so long to get started.

Disclosure

Between 2006 and 2010 the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) and the Ministry of Land and Resources (MLR) carried out a full survey of soil pollution in China.

A statistical report on the findings of that survey was released in 2014, with 16% of almost 10,000 testing points across 1,500 surveyed areas found to be in breach of standards. As there are far more polluted sites in China than testing points in this survey, some academics regard the survey as too broad, failing to reflect the real extent of pollution.

Gao Shengda, editor of China Environmental Remediation, an industry website, estimates there are between 300,000 and 500,000 polluted sites in China, 30 to 50 times more than the number of testing points in the 2014 survey.

Following the soil pollution scandal at a Changzhou school this April, environmental protection minister Chen Jining said he wanted to see a detailed nationwide survey of which sites were polluted.

The action plan also calls for an investigation by 2018 into agricultural soil pollution to establish the extent, location and impact on agricultural products, and for the location and risk of pollution at key industrial sites to be understood by 2020.

But given that the earlier, broad survey took almost four years, the difficulties of completing a more detailed study and risk evaluation in the three years before 2020 appear daunting.

Ma Jun, director of the Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE) said: “I’m sure there’s already a map (of soil pollution), but for various reasons it hasn’t been published.”

But soil pollution often isn’t obvious, so if the details of the affected sites and levels of pollution aren’t disclosed, the public cannot have faith in or exercise oversight of remediation efforts.

And ultimately, that will make those efforts less effective. The details of polluted sites and associated pollutants found in the 2006-2010 survey were never published.

Ma told chinadialogue that he thinks the government isn’t releasing existing information as it is worried about causing panic. Gao Shengda added that the MEP is currently emphasising the need for an “orderly release” of information.

Civil society maps

After the Changzhou scandal, the IPE published a map of soil pollution risk – the first such map to be made available to the public in China.

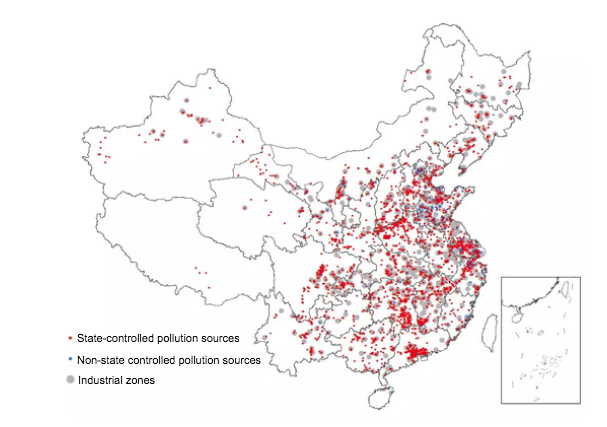

The IPE produced its map by filtering its pollution database, identifying 4,500 companies in 13 polluting industries such as chemicals, mining and metals. Of these, 3,998 were state-controlled and 502 non-state controlled, and 729 industrial zones home to the same industries. These locations were then marked on a map of China.

Map produced by filtering of pollution source data. Source: IPE

This doesn’t show sites of soil pollution or the degree to which these are contaminated, only possible sources of pollution. But Ma hopes even this compromised effort will promote the gradual release of more information and increase the public appetite for such data.

The locations marked on the map will be brownfield sites, and if the companies currently there decide to move, the sites will need remediation, which involves the removal of contaminants to protect human health and the environment.

By tracking when such moves take place, an initial set of data on polluted sites could be built up, helping to make information on polluted sites more open.

During this process, monitoring of relocations and emissions will require public participation, which will help everyone understand the dangers of soil pollution.

“That means that when the MEP does publish pollution data, people won’t just panic,” said Ma.

Ma also thinks that openness of information is a gradual process. Maps such as that produced by the IPE rely on data on major polluters released by the MEP over the last decade, and increasing disclosure of regulatory information.

The action plan does include openness of information. Local governments will be required to produce a list of companies subject to monitoring of soil pollution based on the location of industrial and mining companies and their emissions, with companies on that list to carry out monitoring of soil pollution at their sites and make the findings public.

But it is still unknown exactly what that information will consist of.

Ma hopes that will be clarified as soon as possible. He worries that only aggregate data will be released, rather than information on specific sites and pollutants.

Also, existing systems for disclosing pollution information haven’t covered particular pollutants, which can be hugely harmful even in tiny quantities.

If China was to follow the example of the US Superfund law, companies would be required to publish an inventory of emissions of harmful substances – which is hugely helpful for preventing and monitoring such pollution.

It is also important to consider where the information is published. The soil action plan doesn’t mention a platform for disclosure. “If you don’t have a platform, like the one for the Air Quality Index, the companies don’t know where to put the information, and nobody knows where to find it, which makes disclosure meaningless,” explained Ma.

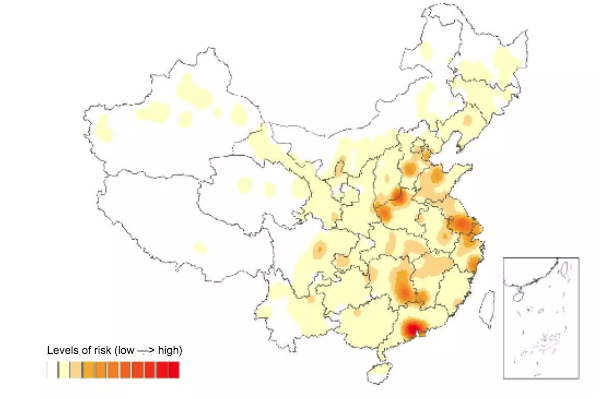

Map of levels of risk, based on locations of 4,500 companies in key industries and over 700 industrial zones. Source: IPE

Liability

But even if the scale of China’s soil polluted is eventually disclosed and catalogued, the huge costs of dealing with pollution will remain a huge challenge.

Zhang Junjie, an assistant professor at University of California, San Diego, told chinadialogue that the most important issue is to decide who is liable, which in turn would dictate where the money comes from.

He believes the action plan’s principles of “polluter pays” and lifetime liability for pollution should be made as powerful as those in the US Superfund law.

But currently, China’s action plan does not specify what form that liability takes (on which companies should contribute to a clean-up fund, to hire a third party to carry out remediation) so further discussion is needed.

Meanwhile, Ma worries that the existing regulation, which makes the purchaser of a site liable for historical pollution, could be a loophole that companies could exploit if they are unable to deal with the problem.

Existing regulations might also make it possible for companies to opt for bankruptcy and avoid paying for a big clean-up, which would require the government to step in.

Funds

But as Chen Jining pointed out at a meeting early this year, the point of the “big clean-up” of soil pollution is risk management. The action plan is not meant to provide financial resources for restoration – rather it aims to combine funds, such as those for dealing with heavy metal pollution, into a single soil pollution fund.

However, that pot of cash is deemed insufficient to deal with the huge scale of the problem. The heavy metal pollution fund was set up in 2010 and has received billions of yuan in funding every year, with a sharp increase last year, to over 9 billion yuan (US$1.36 billion).

And this is tiny in comparison with the trillions of yuan that will be needed to clean up soil pollution. The action plan calls for more government spending and the use of Public Private Partnerships, but as yet there are no specific programmes for doing this. Currently it is unclear to what degree the private sector will be involved.

Regardless, as Chen Nengchang says, “it is progress to at least have an action plan.” Ma Jun said much more clarity is needed, and hopes to see more details and improvements in a follow-up soil pollution law.