Every Chinese person knows about one place in Siberia – Lake Baikal. It is not necessarily famous for its unique biodiversity or for being the deepest lake in the world. Every winter, radio broadcasts warn Chinese listeners about “cold air masses that are moving in from the Lake Baikal”. It’s also the subject of a popular folk song.

Lake Baikal contains 20% of the world’s freshwater resources and affects the regional climate of North Asia and the Arctic Basin. The lake is home to 2,500 aquatic species and local communities in Mongolia and Russia revere the lake as the “Sacred Sea”.

See also: Backward steps at Lake Baikal

See also: Global warming affects Lake Baikal

Chinese people are beginning to value Lake Baikal and are increasingly coming as tourists to see it. Some visitors are even investing in the risky tourism business around the lake. Recently the China-based Well of the World company proposed pouring Baikal water into bottles to quench Chinese thirst. But this nature-friendly relationship could be severely damaged as the China Export-Import Bank (China EXIM Bank) has pledged a soft loan to Mongolia for a project that may tip the fragile ecological balance of the ancient lake.

The Selenge River drains much of northern Mongolia into Lake Baikal.

On November 11, 2015, Mongolia and China issued a joint statement that calls for the development of large industrial projects including major coal projects and hydropower. For that Mongolia secured a US$ 1 billion (6.6 billion yuan) loan from the China EXIM Bank, which it intends to use for the construction of the Egiin Gol hydropower project. A US$ 100 million concession for access roads and bridges has been awarded to China Gezhouba and construction activity began during the harsh winter months.

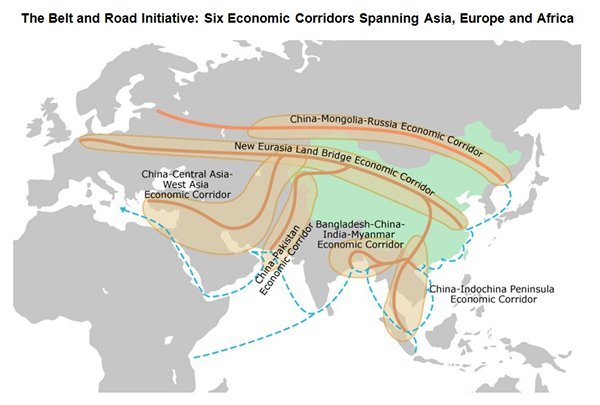

These energy schemes are essential parts of China’s New Silk Road Initiative, aimed at integrating the country with its neighbours. But in the spring, Chinese authorities intervened to suspend the dam project until due diligence is carried out on transboundary impacts. This highlights the lack of environmental safeguards and green development guidelines under the Silk Road, which provides polluting state-owned companies that are, no longer welcome at home, with opportunities to invest in infrastructure, energy and heavy industry in neighboring countries.

Dam damage

The hydropower project is located on the Eg River near its confluence with the Selenge River, the main source of Lake Baikal. Feasibility studies for the hydropower dam were completed ten years ago under the auspices of the Asian Development Bank in an ill-directed attempt to boost renewable energy use in Mongolia. Although electricity generation potential of the rapidly drying rivers of Mongolia is 3,000 times smaller than that its wind and sun potential, the World Bank followed the Chinese script. Its feasibility studies for several coal projects and two more large dams in the Baikal Basin, one of them – the Shuren Hydro dam – is planned on the Selenge River itself.

Mongolian government agencies are looking at 10 more hydropower dam locations on the Baikal Basin, justified by the need to “de-carbonise” the energy sector and achieve energy independence from Russia.

Climate stricken lake

The International Union for Conservation of Nature reported in 2015 that the combined effects of the projects on the lake are not fully known and could seriously damage its UNESCO World Heritage status.

The World Heritage Committee discussed the dams that could damage Lake Baikal at a meeting in Bonn in July 2015. The committee set forth requirements for an impact assessment of Egiin Gol and two other projects, as well as a cumulative impacts assessment for all three dams. The committee requested Mongolia (and by default, China) to hold approval of the projects until all assessments for dams have been completed and reviewed by the World Heritage Centre.

Lake Baikal (Image by Sergey Gabdurakhmanov)

The ecosystem of the lake has already been severely damaged by the construction of the Irkutsk Hydropower plant built upstream in Russia in 1960. This, along with prolonged drought in Mongolia, has led to a decline in the lake’s water levels. Climate change and pollution combined to create an ecological and socio-economic crisis on the Baikal Lake shore with massive invasive algae blooms, a decline in fisheries and an increase in severe peat fires in the Selenge River delta.

Weak standards

So how did China, which is prioritising a cleaner environment at home, and promoting “green development” globally as a G20 leader, make such a dangerous mistake by starting work on Egiin Gol?

This is a consequence of gaps still present in the design of China’s New Silk Road Initiative (or One Belt One Road) aimed at integrating the country with its neighbours and global markets. However great it is at boosting new economic cooperation, the New Silk Road Initiative so far lacks clear environmental safeguards and specific green development guidelines. Grand plans for “new economic corridors” are not subjected to strategic environmental assessments to avoid environmental damage and select the best alternatives.

Map sourced from the Hong Kong Trade Development Council

Finally, there is no mechanism for consultation with stakeholders living along the Silk Road. Without this, Chinese investors lack information on actual environmental and social risks. Or they get it too late, as in this case when supervising agencies ordered Gezhouba to stop construction.

China’s National Development and Reform Commission suspended the project over concerns about transboundary impacts of the dam project, according to sources within the company and the Mongolian foreign ministry. China EXIM Bank has also asked their Mongolian counterparts to conduct due diligence on Egiin Gol. Meanwhile the project is in limbo.

Most likely, Chinese agencies pursuing energy cooperation with Mongolia had not assessed the environmental effects of various investment options or the associated trans-boundary water issues. Then, all of a sudden this spring, the EXIM Bank received a letter from the people of Russia’s Kabansk District in the Selenge River Delta and learned that the project it was supporting could harm Lake Baikal, which is the source of cold winter air in China.

An alternative way forward was proposed by the 64,000 people who signed a petition last year asking Mongolia, Russia and China to support solar and wind instead of hydropower and coal. China, with its ambitions to develop a large-scale renewable industry, should listen to these voices.

An earlier version of this article was published on Russia Beyond the Headlines.