This summer, the inhabitants of the sleepy German town of Grenzach-Wyhlen are confronted with the unusual sight of three giant yellow drilling rigs. The machines hover over the site near the Rhine River where Swiss drug maker Roche prepares to excavate and dispose of around 280,000 tonnes of contaminated soil.

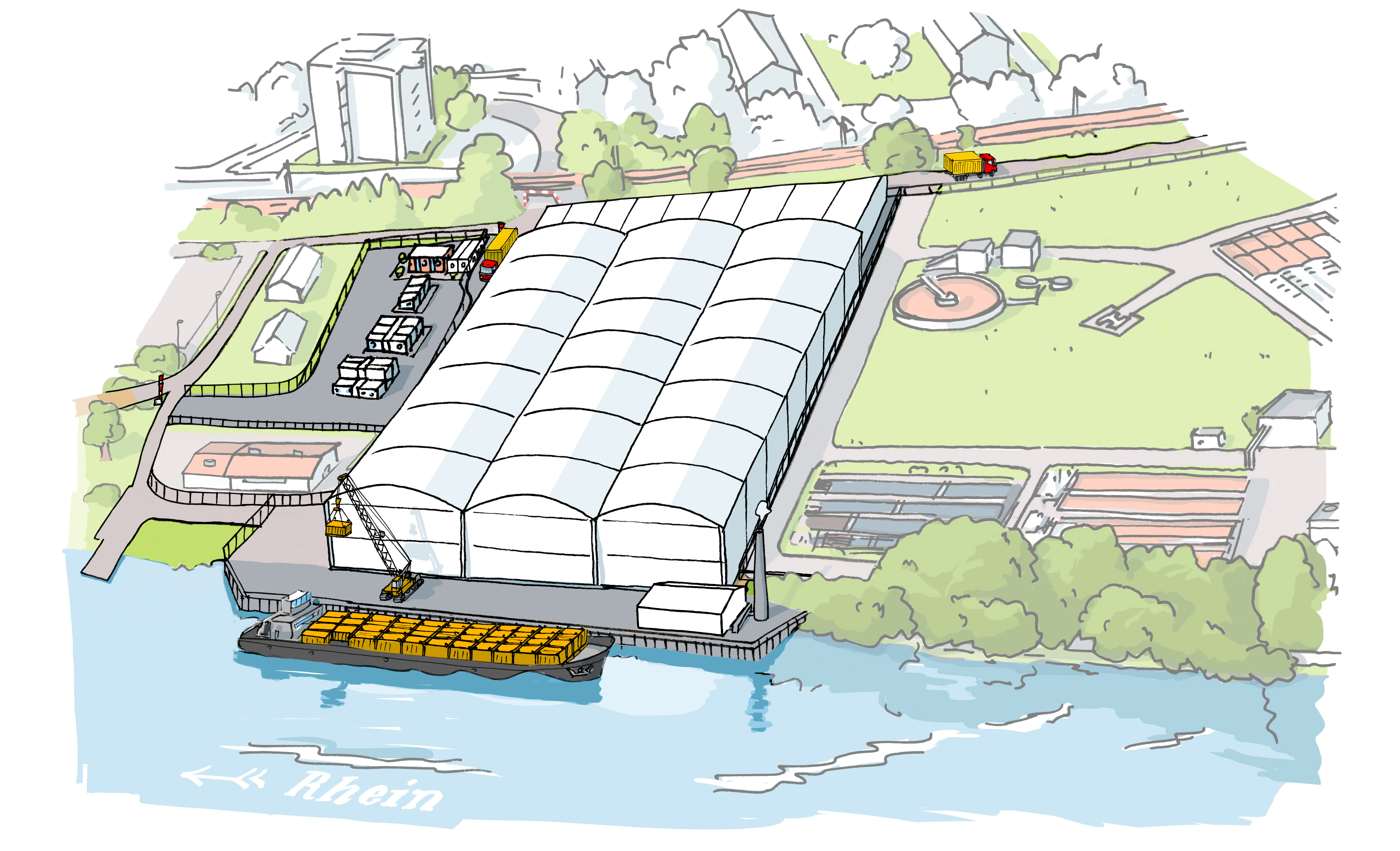

Over the next few months, the machines will drill 888 interlocking piles deep into the ground to form an underground retaining wall. The excavation site will be covered by a lightweight hall where workers will fill the polluted soil into containers destined for thermal treatment plants in Germany and the Netherlands. The containers will be transported there from a nearby train terminal. At a later stage, barges will also be used to transfer the containers to the terminal via a newly built temporary pier at the bank of the Rhine.

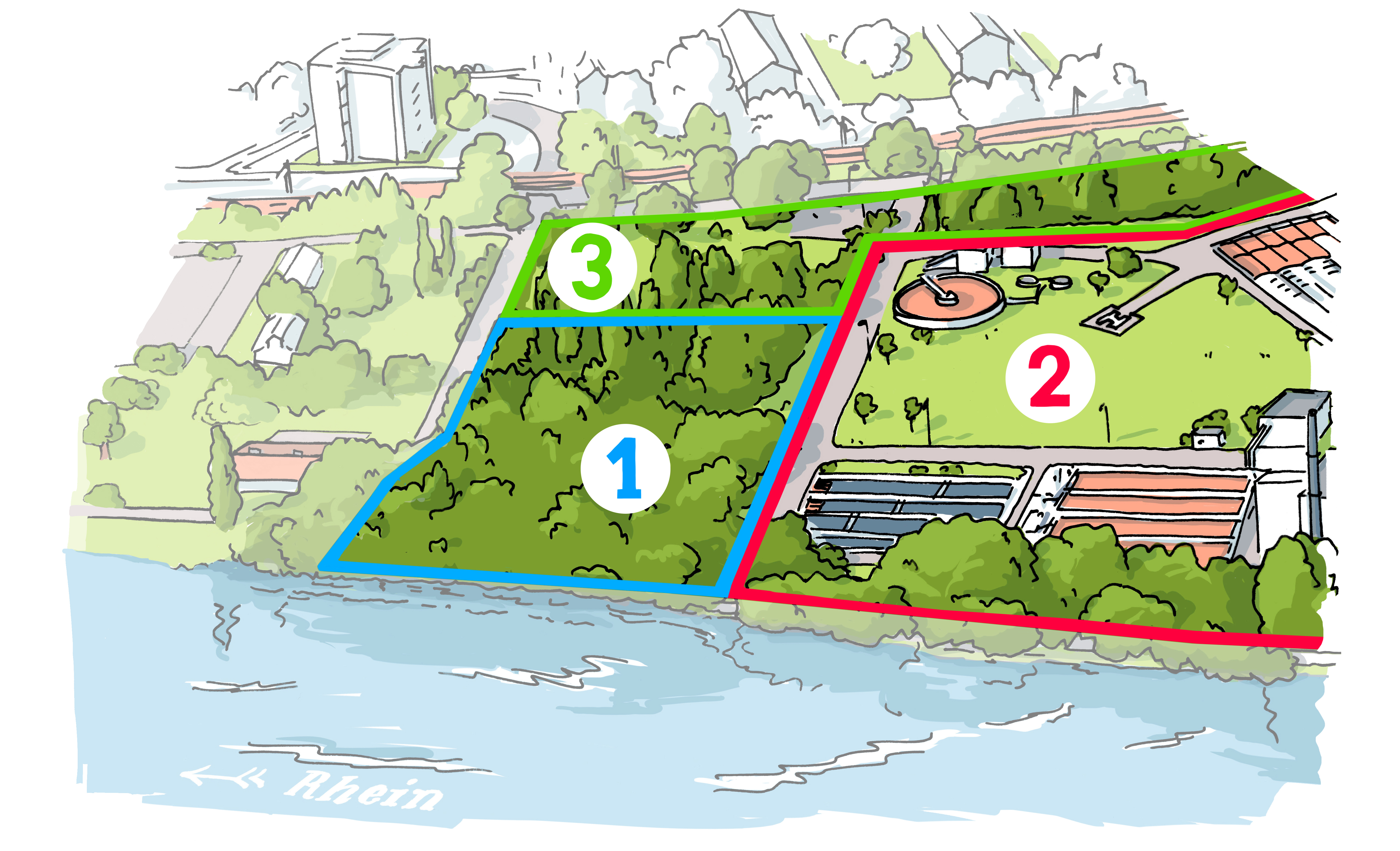

Division of contaminated land in Kesslergrube. Roche has committed to cleaning up perimeters 1 and 3. BASF is responsible for perimeter 2. (Source: Roche)

The Roche excavation site is covered by a hall. Containers filled with polluted soil leave the site via truck to the nearest train terminal, from where they will be transported to thermal treatment plants. Roche also built a temporary terminal to transport containers on barges. (Source: Roche)

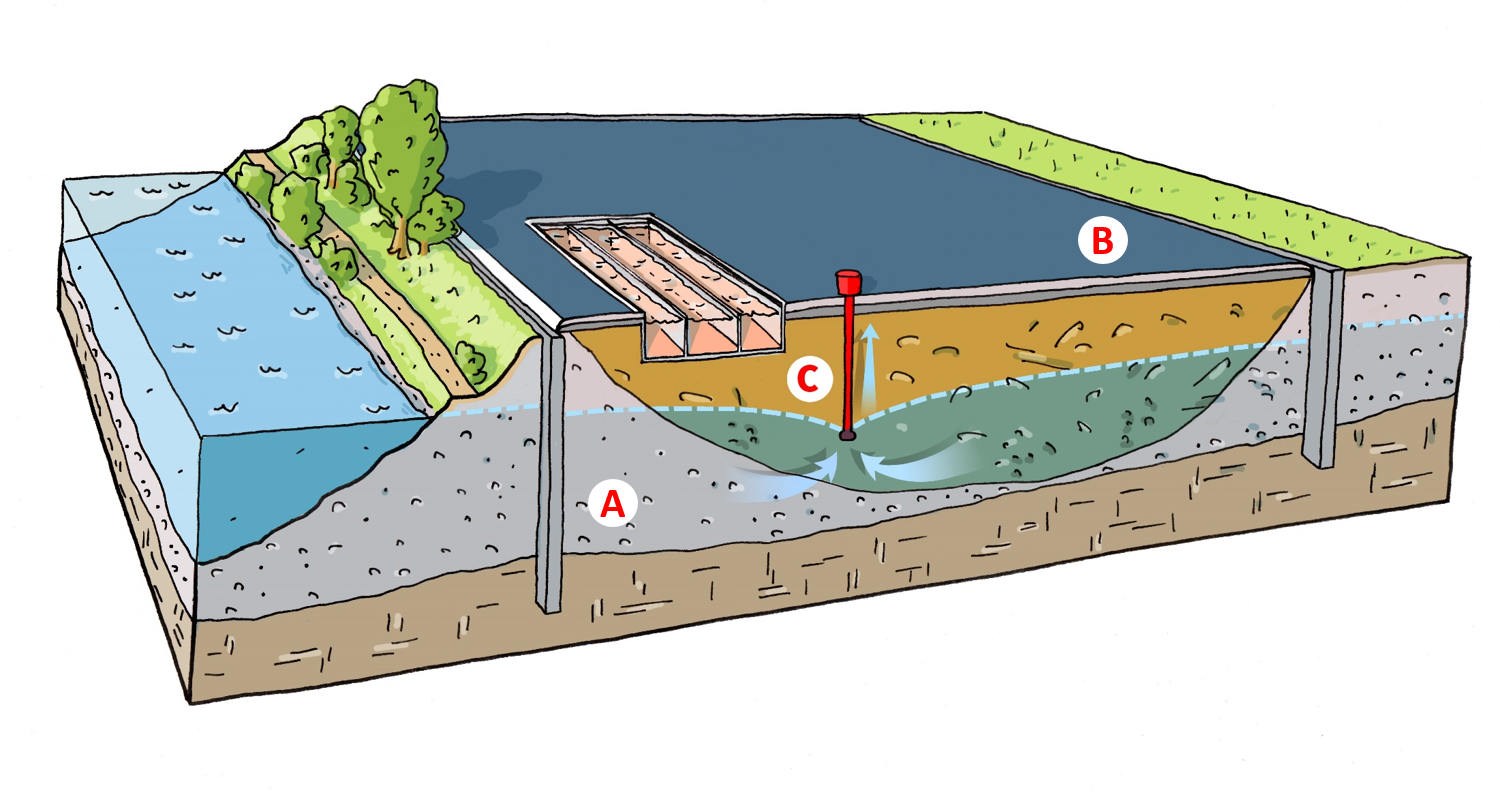

In the BASF remediation plan, the contaminated material is enclosed laterally by a one meter thick wall (A). The surface is sealed with a seven-layer cover (B). A drainage and cleaning system (C) ensures that no pollutants are released into the environment. A permanent control system monitors the measures’ effectiveness. (Source: BASF)

To the knowledge of participants and external experts, Roche’s remediation efforts at the Kesslergrube landfill is the biggest soil clean-up project currently under way in Germany. The site at the German-Swiss border has also become a symbol for clashing traditions and philosophies when it comes to soil remediation.

Roche is only responsible for one portion of the site, another portion is owned by German chemical corporation BASF. Both Roche and the Swiss chemical company Ciba, which was bought by BASF in 2009, contributed to the pollution. The former gravel pit was operated as a mixed-use landfill between the 1950s and the 1970s, where communal household waste and construction rubble were dumped alongside toxic industrial waste such as heavy metals or chlorinated solvents.

There are no acute risks to the population, as long as the groundwater is monitored and treated, but the inhabitants of Grenzach have lasting memories of a chemical spill on the Swiss side of the border in 1986, when an accident at a storehouse by Sandoz released tons of pollutants into the Rhine, turning it red. The Kesslergrube’s location close to the river was one of the motivations for a 2011 decision by the authorities that the site was “in need of remediation”.

Roche and BASF evaluated their options – and reached very different conclusions. BASF decided to build an enclosure around the contaminated material and to seal the surface with a seven-layer cover to prevent pollutants from escaping.

The authorities decided that this solution, projected to take two years and at a cost of 30 million euros (222 million yuan), satisfies the hazard prevention requirement of the German soil protection law. However, it does not satisfy the expectations of the local citizens’ initiative, who filed an administrative opposition against the company’s plans. Local residents have said that capping the toxic site will not remove the source of the problem and will discourage new commercial activities in the area.

The angry citizens feel validated by Roche’s activities next door. “We are determined that excavation is the most sustainable solution because it removes the source of the contamination and there will be no future need for maintenance,” said Roche’s Chief Remediation Officer Richard Hürzeler, who guides the frequent visitors through an information centre the company has set up next to the construction site.

The modern meeting room on the second floor of the cube-like info box offers a panorama of the construction site. Downstairs, a multimedia exhibition explains the history of the landfill and the remediation plans. Visitors experience a simulation of what it would be like to work on the excavation underground.

Roche declined to comment on the cost of the visitor centre, but it would have been only a fraction of the 239 million euros the company plans to spend on the entire project. This number is not only eight times higher than the price tag for BASF’s enclosure plan, but it amounts to almost half of the 538 million euros BASF spent on its worldwide environmental protection and remediation efforts in 2015.

Two countries, two philosophies

“Switzerland is the most advanced country in the area of soil decontamination,” says Peter Donath, a retired chemist and former environmental manager at Ciba, who is now an active member of the citizen’s initiative against Ciba’s successor BASF. The Swiss law stipulates a risk-based assessment, but it implicitly favors excavation by demanding that a site will no longer have to be actively managed within two generations.

“Excavation is not the legal default, yet it is the method that is most often used in Switzerland,” said Christiane Wermeille, head of the Contaminated Sites Section at the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment. Switzerland’s high demand for building land creates incentives for owners to delete their sites from the national register of contaminated sites as quickly as possible.

One might also add that Switzerland is a very small, very wealthy country, and that it does not share the history of West Germany’s frantic economic rebuilding after World War II or of East Germany’s dirty state-owned heavy industry. More than 37,000 sites in Germany have been remediated or are undergoing remediation. In addition, the German authorities still count more than 320,000 potentially contaminated sites. Last but not least, the location of Grenzach-Wyhlen would explain why Roche cares so much about local public opinion. The German town is essentially a suburb of Basel, the Swiss city where Roche is headquartered. BASF is based in Ludwigshafen, more than 260 kilometres to the north.

Yet in the end, cross-country comparison may be overblown since every remediation decision has to be taken on a case-by-case basis. On some Swiss sites, the risks of excavating toxic material would outweigh the benefits. On the other hand, BAUER Resources, the company that manages the Kesslergrube project as a contractor for Roche, completed excavations in German inner city areas to allow for future construction of underground structures such as parking garages.

Challenges

BASF argues that the pollution problem in its part of the Kesslergrube site differs fundamentally from the one owned by Roche.

According to Uwe Gauglitz, who heads the company’s division for Global Remediation, Soil & Groundwater, the BASF site is less contaminated and more than twice as large as Roche’s, so that an excavation would be even costlier and take longer than the five years Roche has scheduled for its project.

In addition, contrary to Roche’s empty plot, the BASF side is overbuilt with two wastewater treatment plants, which would have to be removed prior to an excavation.

BASF also rejects the notion that a complete excavation is generally the more sustainable method. The company notes that an excavation takes longer to carry out, without immediately stopping the emission source, and that the transport and treatment of hazardous material contribute to a higher carbon footprint.

Gauglitz admitted that a sealed site has to be monitored for decades, for example to ensure that the ground water inside the encapsulation stays below the level outside the wall. But he expressed confidence that more sustainable and cost efficient ways to treat material on site will be available in the future.

Costs and benefits

In the present, cost-benefit calculations play a big role in soil remediation efforts, and legislators face the challenge of drafting the regulations and creating financing models – especially for cases where the initial polluter cannot be clearly identified or where the responsibility rests with governments and communities.

The US collected taxes from the chemical and petroleum industry in the 1980s to build up its so-called “Superfund” for cleaning up abandoned or uncontrolled hazardous sites. Federal and local governments across the EU grant subsidies to communal remediation efforts.

Many developing countries will face similar issues when drafting their own laws and rules. China’s recently-released action plan for tackling soil pollution has been criticised for lacking details on funding.

Lessons for China?

Roman Breuer, executive board member at BAUER Resources, which is bidding to participate in planned pilot projects in China, warns that it would be misguided to rely too heavily on private investor money to clean up the pollution. “Financial models such as private-public partnerships don’t work in cases where the costs of remediation would be higher than the value of the land,” he said.

The situation in China is similar to East Germany, where different types of state-owned heavy industries created overlapping contamination across large swaths of land. Waiting for one big private company to pick up the entire bill, as Roche does in Grenzach-Wyhlen, won’t be a realistic approach for China.